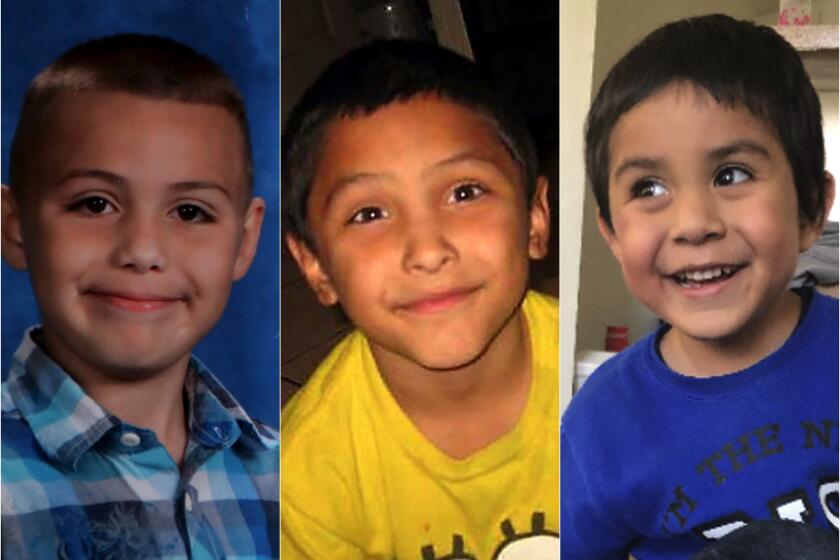

Parents plead no contest to killing and torturing their 4-year-old son, Noah Cuatro

The parents of a 4-year-old Palmdale boy pleaded no contest Friday to murdering and torturing their son, in a case that brought renewed scrutiny on Los Angeles County’s child welfare system.

Ursula Juarez, 30, and Jose Cuatro, 32, were accused of killing their son, Noah, in July 2019, a month shy of the boy’s fifth birthday.

In an Antelope Valley courtroom, both sat masked and in orange jumpsuits next to their attorneys. Noah’s great-grandmother, Eva Hernandez, watched nearby, occasionally crying and surrounded by her family and family members of other murdered children.

Cuatro pleaded no contest to first-degree murder and torture and faces 32 years to life in prison. Juarez pleaded no contest to second-degree murder and torture and faces 22 years to life in prison.

Their sentencing is scheduled for April 30. They both waived their right to appeal.

Juarez cried as she left the courtroom.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Jonathan Hatami called her display of emotion “crocodile tears” and said that the woman had never shown remorse.

“If Ursula really cared, she would have admitted on Day 1 what happened in this case and what Cuatro did,” Hatami said. “I think those tears are for her, because she knows she’s going to spend 22 years to life in prison.”

Cuatro and Juarez’s attorneys were not available to comment after the hearing.

After 6 p.m. on July 5, 2019, Cuatro and Juarez summoned authorities to their Palmdale apartment complex. “Help, please, somebody,” Cuatro told a dispatcher in a panicked 911 call. The parents claimed that Noah had been swimming in the complex’s pool and stopped breathing.

But when paramedics arrived, they found the boy unconscious in his family’s apartment and became suspicious.

“Things were just not adding up to what the father had already told us — that this child is down in a pool for over 30 minutes, and all of a sudden now he’s dry with a pair of tan shorts that were not wet,” firefighter paramedic Chad Sullivan testified.

At the scene, Noah’s body showed “mottling” around his neck — a sign of strangulation, according to case records.

In the emergency room, the boy had bruises across his chest, arms and legs, with a large mark on his forehead, Det. Susan Velazquez testified.

“You knew in your heart that there was something more that he couldn’t tell us, that his body was telling us a story, and we needed to figure out what was going on,” Velazquez said.

Noah died the following day, July 6, at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. A group of doctors and nurses gathered round his body, holding his hands as he took his last breath.

Noah Cuatro’s life and tragic death offer a sobering window into how race, cultural sensitivity and trust collided inside the agency.

Dr. Carol Berkowitz, a UCLA pediatrician, examined the body and concluded that although Noah had “so many injuries,” including rib fractures that were at least two weeks old, he died from suffocation.

Experts also found trauma on the boy’s rectum but could not determine what had penetrated him to cause the injuries.

A grand jury indicted Cuatro and Juarez in 2020, charging each with one count of murder and one count of torture.

Juarez was also charged with child abuse that is likely to cause death, and Cuatro was charged with assaulting and sexually penetrating a child under 10. The child abuse, assault and sexual assault charges were all dismissed as part of the plea deal.

Cuatro’s case — one in a string of high-profile deaths of children in the Antelope Valley, including Gabriel Fernandez — prompted renewed scrutiny of L.A. County’s Department of Children and Family Services.

Hernandez, Noah’s great-grandmother, filed a lawsuit against L.A. County in 2020, accusing DCFS of failing to prevent his death and neglecting to fully investigate and stop abuse by his parents. Lawyers for Hernandez recently asked a judge to compel former DCFS Director Bobby Cagle to answer questions under oath about Noah’s case.

The lawsuit centers on a unique part of Noah’s case: From birth, the boy was under the agency’s watch.

As a newborn at the hospital, DCFS whisked him away from his parents because the agency accused Juarez, his mother, of abusing an infant half-sister and causing skull fractures. Noah’s first weeks of life were spent cycling through foster homes until he eventually reached Hernandez’s home.

Anthony, Noah, Gabriel and beyond: How to fix L.A. County DCFS

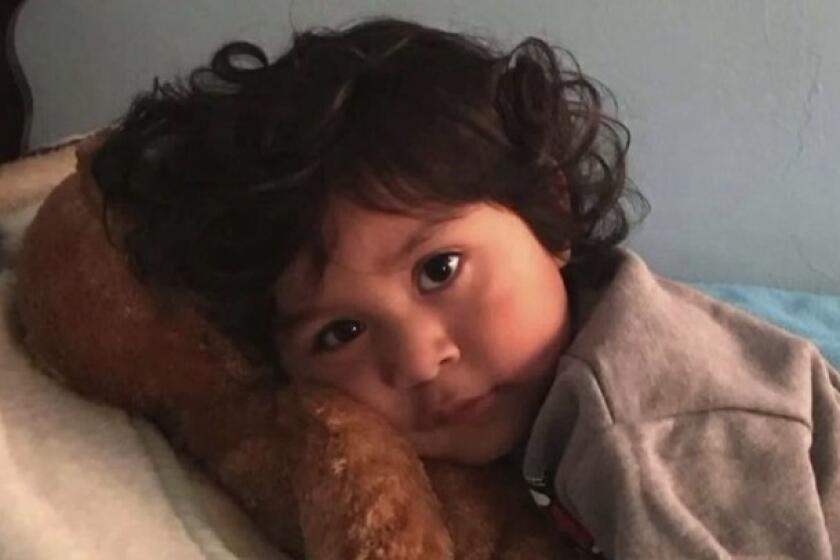

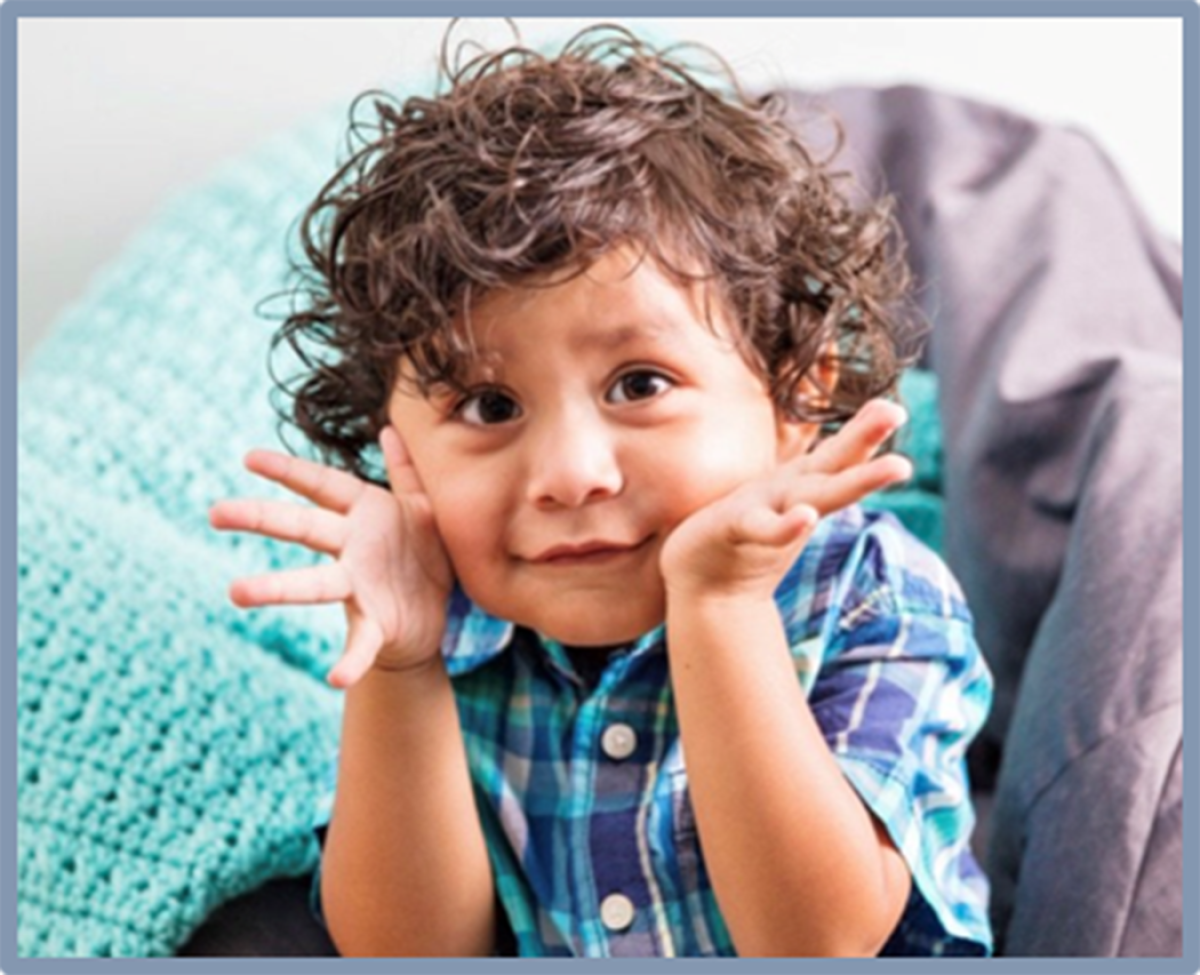

With Hernandez, Noah formed arguably the most consequential and loving bond of his brief life, sometimes addressing his great-grandmother as “mommy,” according to his child welfare records obtained by The Times.

And during his time away, Noah’s parents developed a grudge against DCFS, feeling that the agency had robbed them of the first months of caring for their son.

Shortly before he turned 1, Noah returned to live with his parents after DCFS could not prove the allegation of abuse against Juarez. Once under their care, his health took a tailspin. His parents missed several medical appointments, prompting Kaiser Permanente to alert L.A. County’s child abuse hotline of possible neglect.

Investigating further, social workers realized that Noah had gained only a few ounces from February 2015 to October 2016 and remained at around 17 pounds, a dramatic halt to his growth.

“He appeared very thin. His eyes were hollow,” said Jennifer Montano, who worked on Noah’s case at the time. Juarez claimed Noah ate too much, which made him vomit and thus not gain weight.

For the second time, case workers removed him from his parents, citing their neglect and his dire health. For a time, he lived at a home in the San Gabriel Valley for medically fragile children, where he gained several pounds and his development accelerated.

Noah returned to live with his great-grandmother, who recalled him as “a bright little boy.”

“Every day, he’d tell me, ‘Grandma, you know what time it is? It’s time for you to hold me and tell me you love me,’” Hernandez said in an interview.

After nearly two years of living apart, Noah’s parents wanted him back again. His great-grandmother pleaded for Noah to stay with her. “They never bonded with Noah,” Hernandez remarked to a caseworker, “and I think that’s why they treat him the way they do.”

On Friday, Hernandez said she will never understand why Noah’s parents didn’t like the child. She recalled telling Juarez to be proud of Noah, only to have the mother sharply rebuke her compliments.

Despite DCFS opposition, a judge ruled that Cuatro had to return to his parents.

During his last year alive, DCFS grew increasingly alarmed by the boy’s situation, with his lead case worker telling a juvenile court judge that his parents were isolating him and that it was “nearly impossible” to assess his well-being.

An aunt, Maggie Hernandez, made an anonymous call to the child abuse hotline, one of several allegations of mistreatment the agency received about the boy. His aunt reported that Noah would say his “butt hurts” and that his mother “wasn’t feeding him.”

Court-ordered parenting classes are key in child abuse and neglect cases but go largely unregulated in California, a Times investigation has found.

“If he’s vocalizing something’s wrong and he’s having night terrors,” his aunt said, “I feel like something’s going on.”

Noah’s social worker, Susan Johnson, documented marks on his right arm and neck along with a “big bruise” on his left arm. When asked what happened when he did something wrong, Noah told Johnson, “I get hit.” When the case worker pressed for details, he’d backtrack, saying, “I do not get hit.”

Johnson secured an order to remove Noah from his parents and have him undergo a medical or sexual abuse exam.

But Johnson was ultimately blocked from separating Noah from his parents and even faced accusations that she was biased and had an “agenda,” a Times investigation in 2021 found.

Johnson vented in an email to her immediate supervisor, “They seem to not believe that my concerns are valid.” She protested to a senior DCFS administrator and later testified she was “upset” by her removal from Noah’s case.

“I couldn’t believe that they did that,” Johnson testified. “Nobody had ever taken me off a case like that.”

In Johnson’s place, DCFS assigned a staffer who seemed sympathetic to Noah’s parents and, in an email, faulted the boy’s great-grandmother, Hernandez, for causing Johnson “to have doubt with the family.”

“I feel like as a Department we have been picking on this family,” the DCFS staffer, Maggie Vasquez-Ducos, wrote about Juarez and Cuatro in a July 3 email, three days before Noah was killed.

Cagle, then the director of DCFS, stood by his staff’s handling of the case in a 2021 interview with The Times.

“It’s very difficult for, I think, the public especially to understand why those decisions were made, but I’m confident that the decisions that were made were the right ones,” Cagle said then.

After Noah’s death, Eva Hernandez was given custody of Noah’s three surviving siblings. She is in the process of legally adopting them, according to records filed earlier this month in her lawsuit.

Hernandez said on Friday that she takes Noah’s siblings to visit his grave site, where they see Noah’s picture on his tombstone. His 11-year-old brother remembers him, while his two younger siblings don’t.

“He was such a beautiful little boy. He was so loving,” Hernandez said. “The last words he ever told me were, not to ever forget about him. He goes, ‘Promise me, Grandma, don’t forget about me.’ I could never forget about him.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.