Column: Benny Wasserman handled the heat -- in life and in the batting cage

Every Friday morning for more than five years, Benny Wasserman, a retired aerospace engineer and Albert Einstein look-alike actor, put on his Detroit Tigers baseball uniform and went to the Home Run Park batting cages near Knott’s Berry Farm.

In January 2023 he emailed me to say he’d set a goal for himself —to rip 90-mph fastballs on April 2, 2024, his 90th birthday. “I’m calling it 90 at 90,” Wasserman wrote, adding that he was dealing with — but not deterred by — prostate cancer and pulmonary fibrosis.

At the first opportunity, I drove to Cerritos to meet Wasserman and his wife, Fern. They’d met on a blind date at an El Monte pizza parlor and were approaching their 65th wedding anniversary.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

“When I hit a home run, it makes my day,” Benny told me.

“He loves it,” Fern said.

Wasserman took me into his den and played “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” on his organ. He took me into his library — his love of books began as a young man when Carl Levin, a childhood friend and eventual U.S. senator from Michigan, gave him a copy of Jack London’s “Martin Eden” as a wedding present. He showed me the volumes of journals he’d been working on for decades and took me to his backyard, which he’d turned into a miniature baseball park where he hit Wiffle balls off a pitching machine.

I wasn’t sure Wasserman could handle the heat, because a 90-mph fastball is what major league pitchers throw. But he stepped into the batter’s box, the pitching machine cranked, and Benny Baseball went to work.

Ground ball. Line drive. Moon shot.

He made contact on nearly every pitch, with a sharp eye and a quick flick of the wrists. A few of his drives had home-run range.

“We all love him,” said Kris Wysong, the Home Run Park manager. “He hits better than most of the customers do.”

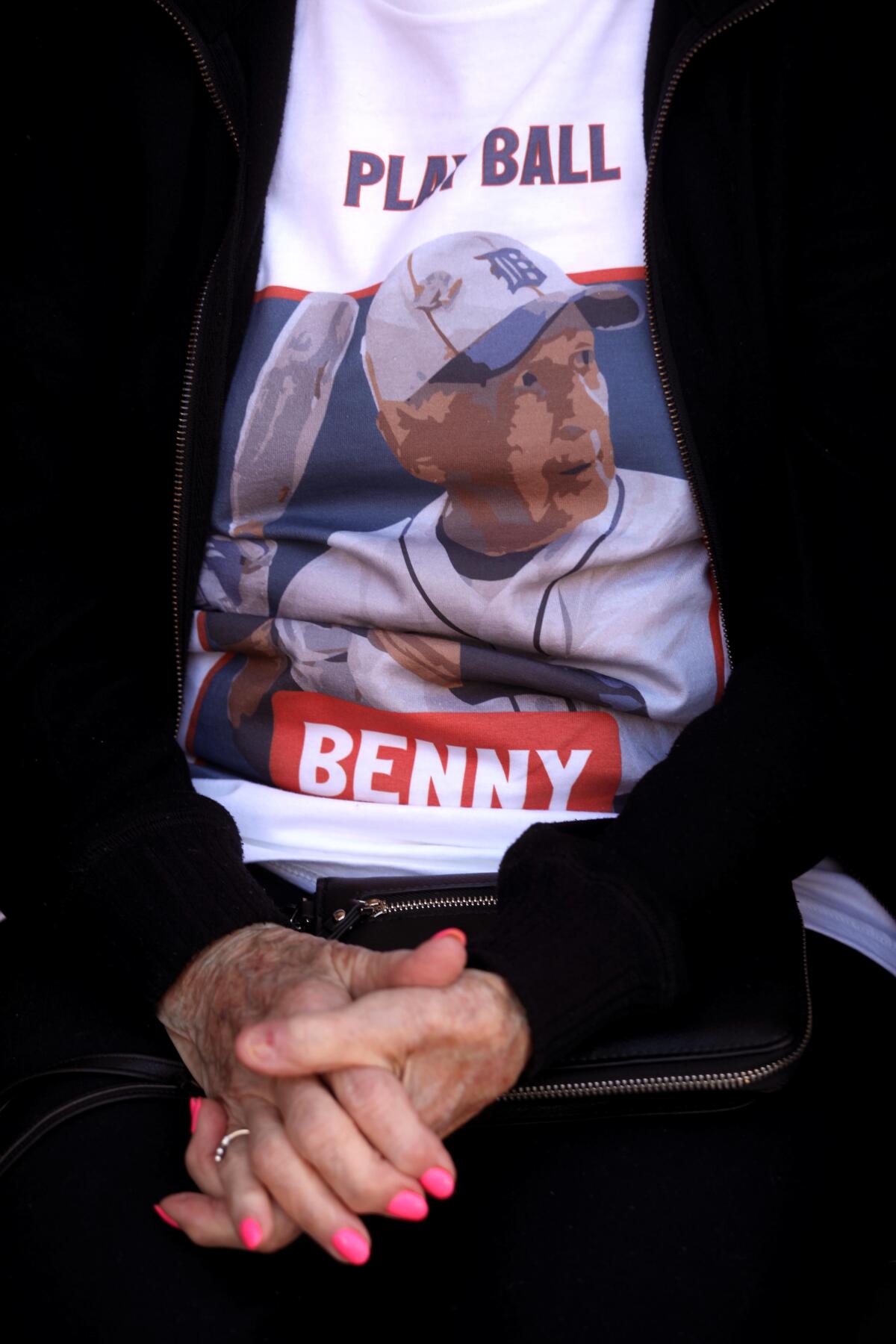

After I wrote a column about him last year, Topps Trading Cards produced a batch of Benny Wasserman baseball cards, and he emailed me a handful of them. ESPN interviewed him and was planning to attend the big “90 at 90” day for a story.

But in mid-February of this year, Wasserman emailed to say his health was deteriorating. He hadn’t given up on his April 2 goal, he said, but his sons — two lawyers and a geriatrician — had persuaded him to visit the batting cage on March 3 and have a “celebration of life” party afterward at his home.

On Feb. 28, he emailed again to say he’d had a blood transfusion and the party had been postponed. “My temperature is fluctuating with associated chills and shivering, and I might have to go back to the ER soon,” he wrote. “Whatever happens I will keep you informed.”

And then, on March 11, I got this email from Fern:

“Just wanted to inform you that Benny passed away this morning!”

Benny Baseball died just three weeks shy of his 90th. His eldest son, Dr. Mike Wasserman, said we can all take lessons from his dad on how to live long and well.

“Having a sense of purpose is a big one,” Mike said, and while his dad had many interests, his trips to the batting cage were a weekly highlight. “Socializing is another,” he said, adding that his father did not lack for company. “And a third one is exercise. I’ve always told my patients, ‘If you exercise regularly, I can reduce at least one prescription medication if not more.’”

Mike, 65, said he thinks doctors are too quick to prescribe medication for patients they don’t really get to know. His father could have fought his cancer more aggressively, he said, but in consultation with his physician son, he pulled back on chemotherapy at times because it made him too weak to do the things he loved.

“In the hospital … my dad wanted to be alert and they were giving him drugs that made him less alert,” Mike said. “Doctors need to think about what they do and how it affects quality of life.”

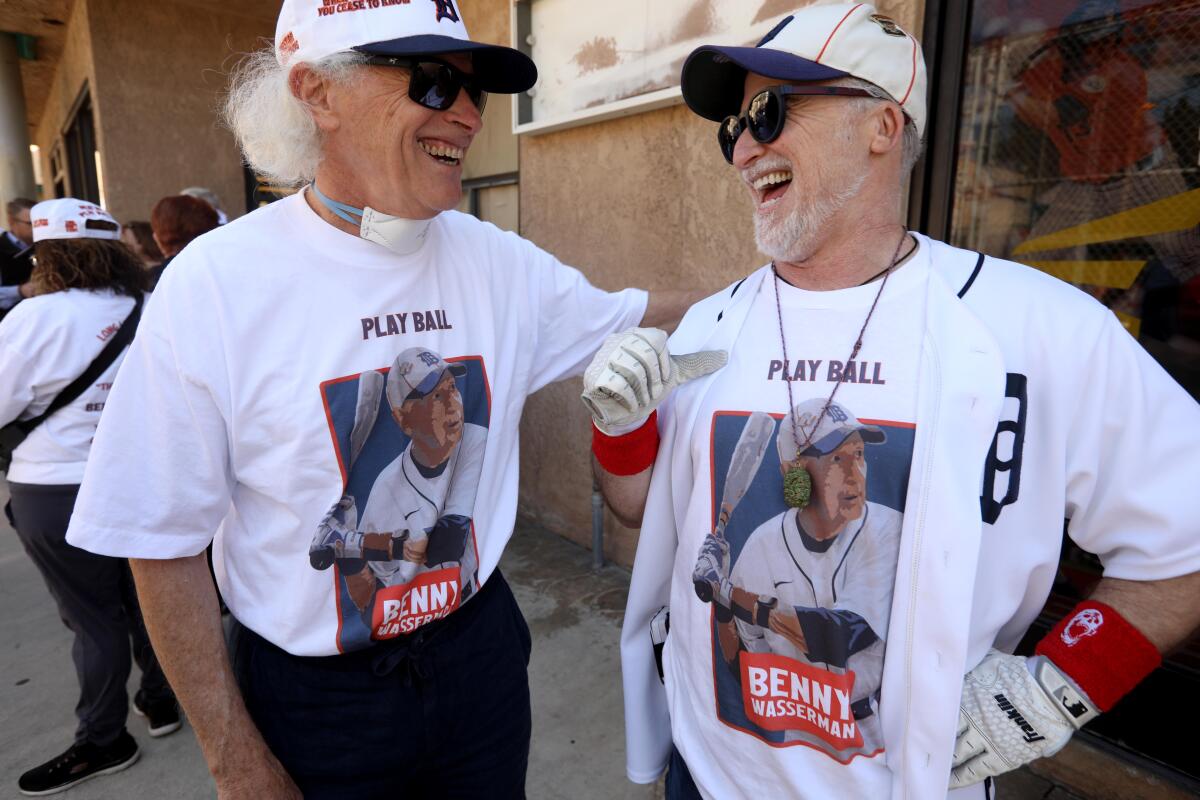

For Wasserman’s family, there was no hesitation about how to celebrate his life. On April 2, friends and family gathered at Home Run Park. Several of them stepped into the same cage Benny always used and took their hacks, but no one got the bat on the ball as consistently as the family patriarch.

Packs of Cracker Jack and Big League Chew bubble gum were nestled in Detroit Tigers souvenir cups near the batting cages. Benny’s favorite chocolate cupcakes were topped with edible copies of his Topps baseball cards.

Wasserman’s sons, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren wore Tigers jerseys bearing Benny’s image, with “Silver Slugger” and “Long Live Benny” on the back. And they wore ball caps emblazoned with some of Benny’s favorite sayings, including, ‘’When you know, you cease to know,” meaning challenge your own instincts, indulge curiosities and keep educating yourself.

“He was the most supportive person in the world,” said grandson Jerett Wasserman, 37, who told me he kept getting into trouble in his late teens and moved in with his grandparents for two years to get straightened out. “If you said, ‘I wanna try surfing,’ he’d say, ‘Let’s go get you a surfboard. Let’s go do it!’ And he taught me to question everything.”

“He was the best grandpa on earth,” said grandson Logan Wasserman, 33, who read the Mitch Albom book “Tuesdays With Morrie” in high school and decided to visit his grandfather every Tuesday to talk about this and that and everything else. Logan is training for a marathon and said that when he doesn’t feel like rolling out of bed for early-morning roadwork, he finds motivation in his grandfather’s refusal to surrender to cancer and lung disease despite being weakened by both.

“He was able to go to the cage a week before he passed away and hit the ball,” Fern said.

But it took every ounce of strength Wasserman had left.

“After his last at-bat, he almost passed out and we had to catch him” before he fell, said Wasserman’s middle son, Craig Wasserman, 61.

Fern said she has a lot of adjusting to do, and she’s grateful that a granddaughter will be moving in to keep her company. She also had a thought about the Oscar-winning movie “Oppenheimer,” which features a scientist named Albert.

“Benny would have made a better Einstein than the one they used,” she said of her husband, who, in his 50s, got an agent and began playing Einstein in television shows, movies and commercials and at special events after someone told him there was an uncanny resemblance.

Wasserman’s sons said their father endured abuse and tragedy as a child. His father took a belt to him, they said, and his mother took her own life when he was in grade school. They said this may explain why he wanted to mentor young people, and why — along with a serious side and an insatiable intellectual curiosity — he extended his childhood right up to the end.

His youngest son, Marc Wasserman, 55, is now following his father’s routine. He goes to Home Run Park every Friday at 10 A.M., just like his dad did, and takes cuts in the same batting cage.

“I’ll be coming here until I’m 90. That’s the plan,” said Marc, who had one last thought about his father.

“He went down swinging.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.