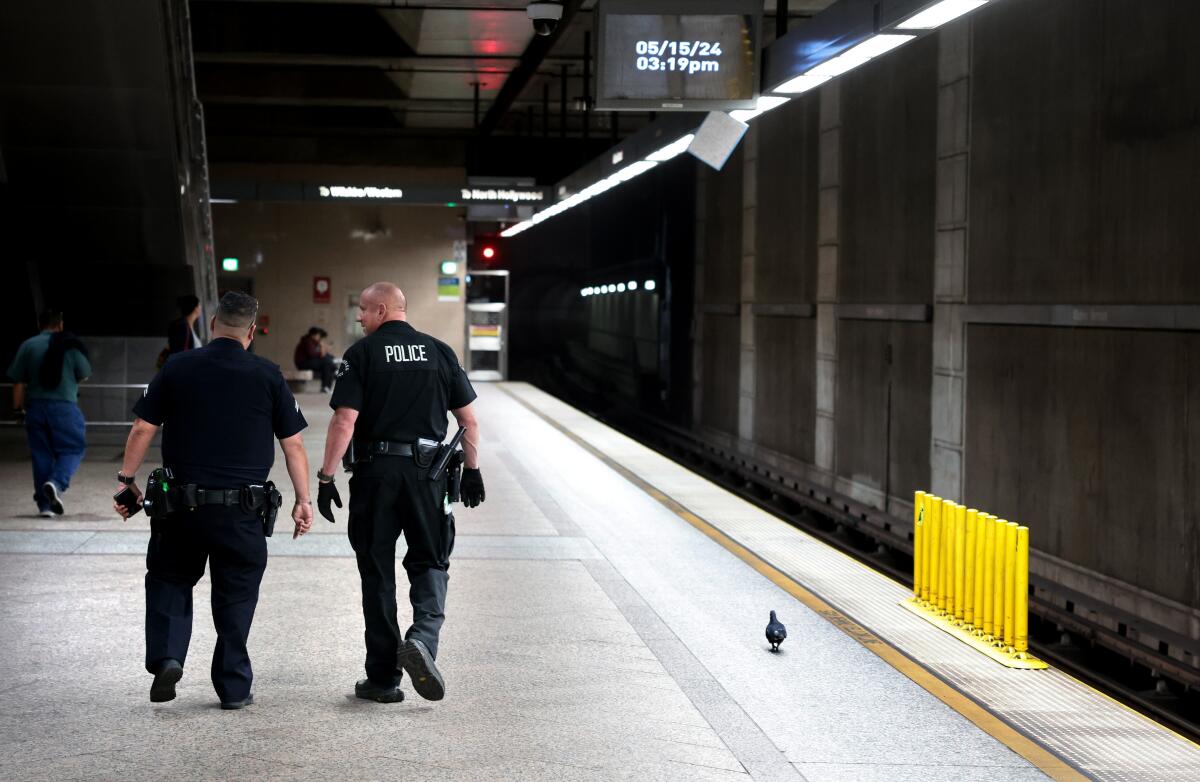

Ex-Metro security chief says police patrols were so lax, they didn’t notice a dead man at station

A dead man was slumped over on a bench at Metro’s San Pedro Street station in February. For nearly six hours, nobody checked his condition, including five Los Angeles Police Department officers who had been patrolling the platform. It took a transit ambassador doing a welfare check to see the man had died, said former Metro security chief Gina Osborn.

“They weren’t even paying attention,” she said. “They weren’t engaged enough to see that there was a human hunched over.”

Osborn, a former FBI agent, said she knows because she and her staff had access to cameras set up around the system, and over her two years at the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority increasingly used them to oversee law enforcement patrols. Her conclusion: They aren’t doing enough.

The security issues surrounding Metro have only grown over the last month after a string of stabbings and two killings on the system. Metro is slated to spend $195 million on law enforcement in the next fiscal year, a figure that continues to rise as the agency is exploring the development of its own police department.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass announced an increase in police deployment this month after a spate of violent crimes, and Metro is investing in a series of tactics to improve the system ahead of the 2028 Summer Olympics — including adding transit security officers, continuing the use of transit ambassadors who assist riders, and additional cleaning at several stations.

The crime wave comes at a crucial time for Metro, which continues to expand its train system with new lines and extensions, including the LAX/Metro Transit Center Station, set to open this year.

The agencies that patrol the system — the LAPD, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and the Long Beach Police Department — said they are doing their job and working with Metro to protect riders, drivers and operators in thousands of buses and trains over more than 100 miles of rail.

Amid a spike in violence on trains and buses, Mayor Karen Bass calls in more police patrols. The fatal stabbing of a 66-year-old subway rider put the transit agency on edge last month, as pressure grew to respond.

“There’s always room for improvement,” said Donald Graham, deputy chief of the LAPD’s Transit Services Bureau. “We will always continue to look and relook at what we’re doing and question whether or not what we’re doing is the best way to do things.”

He said an internal investigation into the incident at the San Pedro Station showed that officers had been doing their job that day. They were there to check that train riders were carrying their Tap cards to pay fares.

Over the last year, under Bass’ leadership, he said, arrests on the system have increased as police crack down on drug use, trespassing and other crimes. Response times are below the city average, he said, and their mission has become more clear: engagement, interdiction to prevent situations from escalating, and becoming a more visible presence.

Osborn was fired in March, shortly after reporting to the agency’s inspector general the alleged failure of sheriff’s deputies to patrol the E Line’s Downtown Santa Monica Station on March 15, she said. Her attorney, Marc Greenberg, said that during her two-year tenure as chief safety officer, she had a “glowing” personnel record and was fired for being a whistleblower.

Metro spokesperson Patrick Chandler said the agency does not comment on personnel matters or pending litigation.

By the time she was ousted, Osborn said, she had become convinced that the LAPD, the Sheriff’s Department and Long Beach police were failing at their jobs, not being proactive enough to keep the buses and trains safe. And when Osborn championed creating an internal police department, she said, she felt stymied by Metro Chief Executive Stephanie Wiggins.

She said she discovered the March lapse during spot checks on the law enforcement agencies.

That day, at 1:37 p.m., she texted Sheriff’s Capt. Shawn R. Kehoe to tell him that nobody had been at the station since 10 a.m. Eight days later, she said, he responded by email that his two deputies were interviewing for internal positions. But she suspected the officers were at a fundraising golf tournament at the Pico Rivera Golf Club for the department’s “Baker to Vegas” running team. The Baker run is an annual relay race held in the desert among law enforcement agencies.

“I don’t think the taxpayers are getting their money’s worth,” she said.

Kehoe told The Times that the department investigated the allegations and found the deputies were at their posts, “which was verified by location positioning technology that the department utilizes.”

“We are committed to working collaboratively with our law enforcement and Metro partners to ensure the safety and security of our transit community and the transit employees,” he said.

An audit by Metro’s Office of the Inspector General in 2022 found that the police agencies had poor visibility on the system and didn’t have adequate means of monitoring the deployment of officers, and that their process of dealing with citizen complaints lacked transparency.

Osborn said she tried to remedy that by installing cameras and negotiating with law enforcement agencies over deployment.

Although there has been improvement, she often met resistance, she said: Long Beach officers had agreed to remove passengers at the end of the A Line in downtown Long Beach but later refused to do so.

“We adhere to our contractual obligations, focusing on enforcing penal code violations to maintain a secure environment on the Metro,” Long Beach police spokesperson Richard Mejia said in an emailed statement. “We value our ongoing partnership with Metro, which is essential in ensuring the safety of both riders and our community.”

When she went to Wiggins for help, Osborn said, she found little support.

A Metro bus passenger was killed in Commerce last week, three months after he arrived in the U.S. It’s the second fatal attack on the system in a month.

One issue that popped up early on, she said, was unsafe conditions for cleaning crews working in the miles of subterranean tunnels and rooms that hold equipment that powers the system, known as ancillary areas. Transients would take shelter there, and some trespassers would store contraband or do drugs in the isolated locations. The hidden pathways and workrooms would often be filthy with human excrement, drug paraphernalia and other debris. Many workers were fearful of attacks and wanted escorts.

After fielding complaints from supervisors, Osborn asked Wiggins to increase the number of armed private security guards from 261 to 500 to assist at the locations. Wiggins rejected the proposal, saying it was too costly.

Osborn came up with a lower number, 419, which she said was rejected because Wiggins said it was “fiscally irresponsible.” Then she proposed 372, with and a quarter of them unarmed, and offered detailed deployment plans. Wiggins ultimately approved the 372, she said. Only half were armed.

At the time, many agencies had turned away from using more armed officers as pressure from the Black Lives Matter movement forced them to assess disparities in enforcement and police brutality. The Metro board was especially reluctant to put more funds into armed law enforcement that critics said made some passengers uncomfortable and too often targeted Black riders. The agency had poured money into social services such as homeless outreach.

Then last May, Metro Deputy Executive Officer William Peterson became ill working in one of the ancillary areas, Osborn said. He told Osborn other workers were becoming sick too. She emailed the deputy chief of risk, safety and asset management to figure out whether it was safe to work in those locations. It was determined the areas were hazardous because of fentanyl, methamphetamine and bacteria. Personal protective equipment should be used, a review found.

Information about the danger in those areas was leaked to CBS reporter David Goldstein, now retired. When Wiggins found out, she blamed Osborn and demanded daily reports on the situation, according to Osborn. Osborn said she made it clear to Wiggins and Chief of Operations Conan Cheung that it was impossible to secure the areas without guards there around the clock. Trespassers continued to get in, often opening emergency doors when a guard’s shift was over.

Wiggins wanted Osborn to transfer the private security guards from Metro bus and rail divisions to the underground locations. Osborn refused, saying it would leave those areas vulnerable, and Wiggins shot off a heated email, according to Osborn.

“Ms. Osborn’s allegations are categorically false,” said Metro spokesperson Chandler when asked about Osborn’s accusations that Wiggins dismissed her concerns about the ancillary areas until the information was leaked to the media, and rejected her requests.

“Ensuring the safety of all our customers and employees is the most important thing Metro’s CEO, leadership team and union leadership are working on,” he said. “Metro is now searching for a new, experienced head of system security who understands the full scope of the job and who will work proactively, resourcefully, and collaboratively to do it.

“Leading system safety and security at Metro requires the acceptance of accountability for all facets of keeping Metro safe — keeping our customers and employees safe on trains and buses, and at our stations, as well as securing the many facilities where our essential employees come to work.”

Osborn was eventually granted 87 more guards but said that Wiggins told her the extra security would end in June.

The proposed fiscal year 2025 budget has funds allocated for 53 new transit security officers. It does not include significant increases for more private security officers.

“It’s a drop in the bucket,” Osborn said.

At the same time, she said, the cost of law enforcement will rise. Last year, Metro paid the LAPD, Sheriff’s Department and Long Beach police more than $200 million, though they were budgeted to receive $176 million, she said, and it is unlikely they will stay within budget this year.

“Wiggins is well aware that LAPD received a significant raise and that they will pass that cost on to Metro,” Osborn said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.