In the last seconds of his life, the 53-year-old actor Vic Morrow was struggling through knee-deep water with a child in each arm. The location, 35 miles north of downtown L.A., was Indian Dunes, which set designers had repurposed as a wartime Vietnamese village.

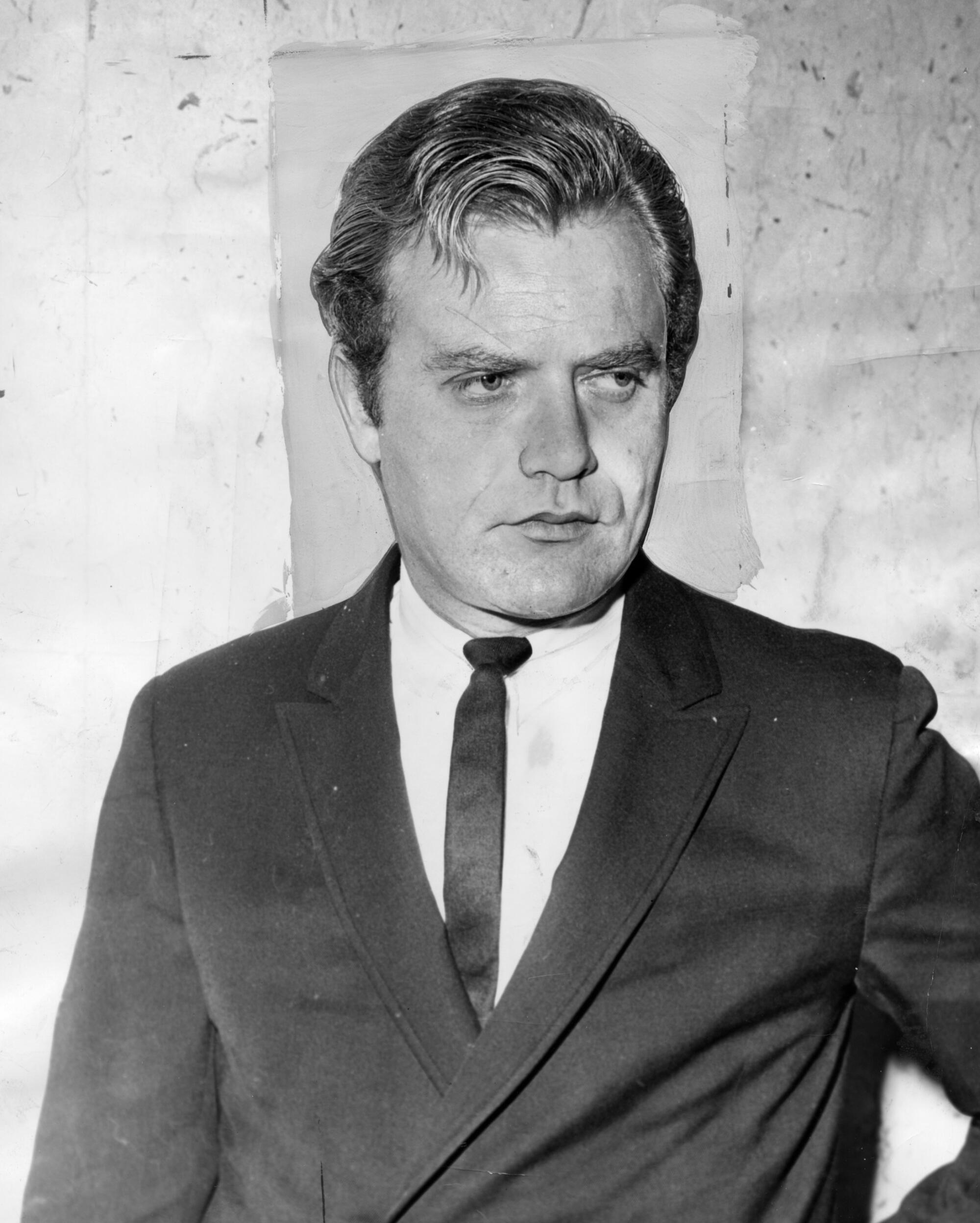

Morrow, who performed as a surly delinquent in “Blackboard Jungle,” a tough soldier in the TV drama “Combat!” and a volatile baseball coach in “The Bad News Bears,” was on this day playing a bigot dreamed up by writer-director John Landis for a segment of “Twilight Zone: The Movie.”

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

Landis, 31, stood in waders nearby while his cameras rolled. Brash and exuberant, he had a reputation as a gleeful impresario of envelope-pushing stunts. He liked to brag about all the cars he had demolished filming “The Blues Brothers” a few years earlier.

For this shot, he had dropped Morrow’s character into the Vietnam War to enact what was intended as a redemption scene, the heroic rescue of two children from a village as it erupted in flames.

“I’ll keep you safe, kids,” Morrow was supposed to say.

The children in his arms — My-Ca Dinh Le, 7, and Renee Chen, 6 — had never acted before. They were not supposed to be on this movie set, at 2:20 a.m. on July 23, 1982. Their parents were receiving a few hundred dollars for their work. The director knew their presence at this hour violated labor laws, but he did not want to use dummies.

About 24 feet above Morrow and the children hovered three tons of noisy metal, a combat-style Huey UH-1B helicopter. As a special effects man fired gasoline-and-sawdust mortars skyward, Morrow stumbled in the water, righted himself and slogged on.

The effects man was not looking up when he shot off the fireball that engulfed the tail rotor, sending the helicopter into an uncontrollable spin. The machine plummeted, crushing and killing Renee. The main rotor blade, 44 feet long, decapitated Morrow and My-Ca. In the footage shown over and over on TV, a curtain of water mercifully blocked the fatal split-second from the camera’s view.

At Morrow’s funeral, Landis struggled to speak and invoked art.

“Tragedy strikes in an instant, but film is immortal,” the director said. “Perhaps we can take some solace in the knowledge that through his work in stage, television and film, Vic lives forever.”

One of Morrow’s friends, Rick Jason, gave a reporter his opinion of the disaster. “It’s just an outlandish freak, and I don’t think you can draw a conclusion from it.”

Sgt. Thomas Budds drew a conclusion. The veteran L.A. County sheriff’s detective believed it was criminal recklessness. He arrived before dawn that day, stepping carefully around the toppled chopper, its big blade sideways in the mud of the Santa Clara River.

He examined the charred remains of the mocked-up village. He examined the three bodies and ordered the river drained, so that remaining body parts could be located. The permeating reek of gasoline would haunt his memory.

Budds, the sole detective on the case, conducted hundreds of interviews in the following months. He spoke to camera operators and assistants, makeup artists and hairstylists. In Budds’ mind, a picture formed of an arrogant, overbearing director who was cavalier about risk and whose subordinates were fearful of second-guessing him.

He had the impression of a director who believed himself in competition for spectacular spectacle with Steven Spielberg, who was co-producing the “Twilight Zone” movie but would not be implicated in the case.

Budds assembled his evidence in two binders and brought them to the district attorney’s office to recommend charges. Pivotal in his decision, Budds told The Times in a recent interview, was the account of cameraman Steve Lydecker, who said Landis ignored his warning about the dangers of the special effects.

“We may lose the helicopter,” the cameraman recalled Landis joking.

There were other signs of recklessness during the filming, Budds thought. At 9:30 p.m. the night before the crash, the two children had been placed in a hut, unaccompanied, near big drums of gasoline.

“All you needed was a spark, and those kids would have been killed.”

At 11:30 p.m., in a precursor to the fatal flight, a fireball singed the face of a production manager riding in the helicopter.

“The explosions were too big. They were put on notice at that point. If the 11:30 event hadn’t happened, I would never have pursued the case.”

Budds added: “It’s like they had a swimming pool and someone almost drowned. You’d think they’d put a fence up.”

Between the fatal crash in summer 1982 and the beginning of his trial in summer 1986, John Landis remained an in-demand artist. He directed the hit screwball comedy “Trading Places” and Michael Jackson’s comic-horror “Thriller” video. “Twilight Zone: The Movie” came out, with the helicopter scene omitted.

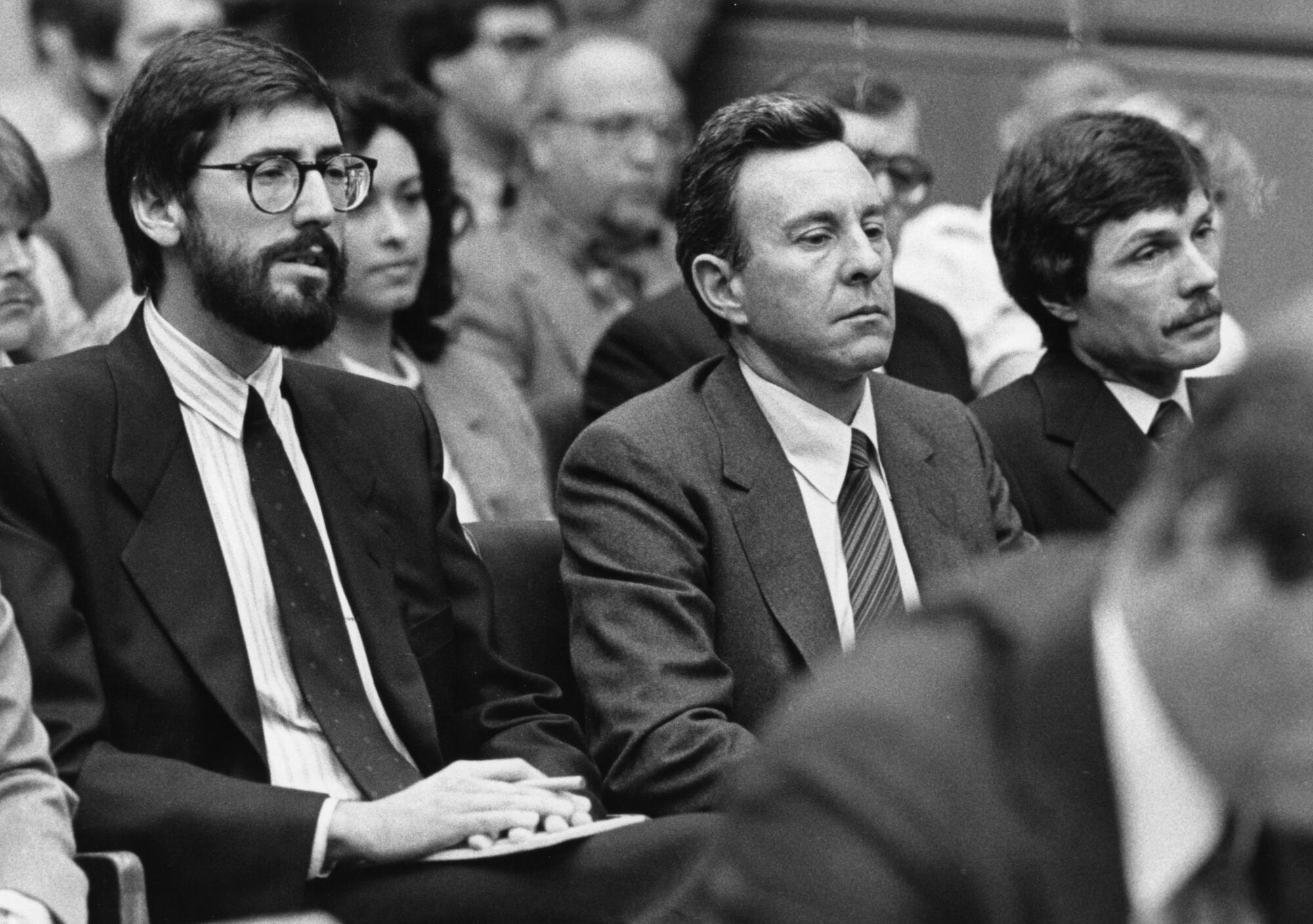

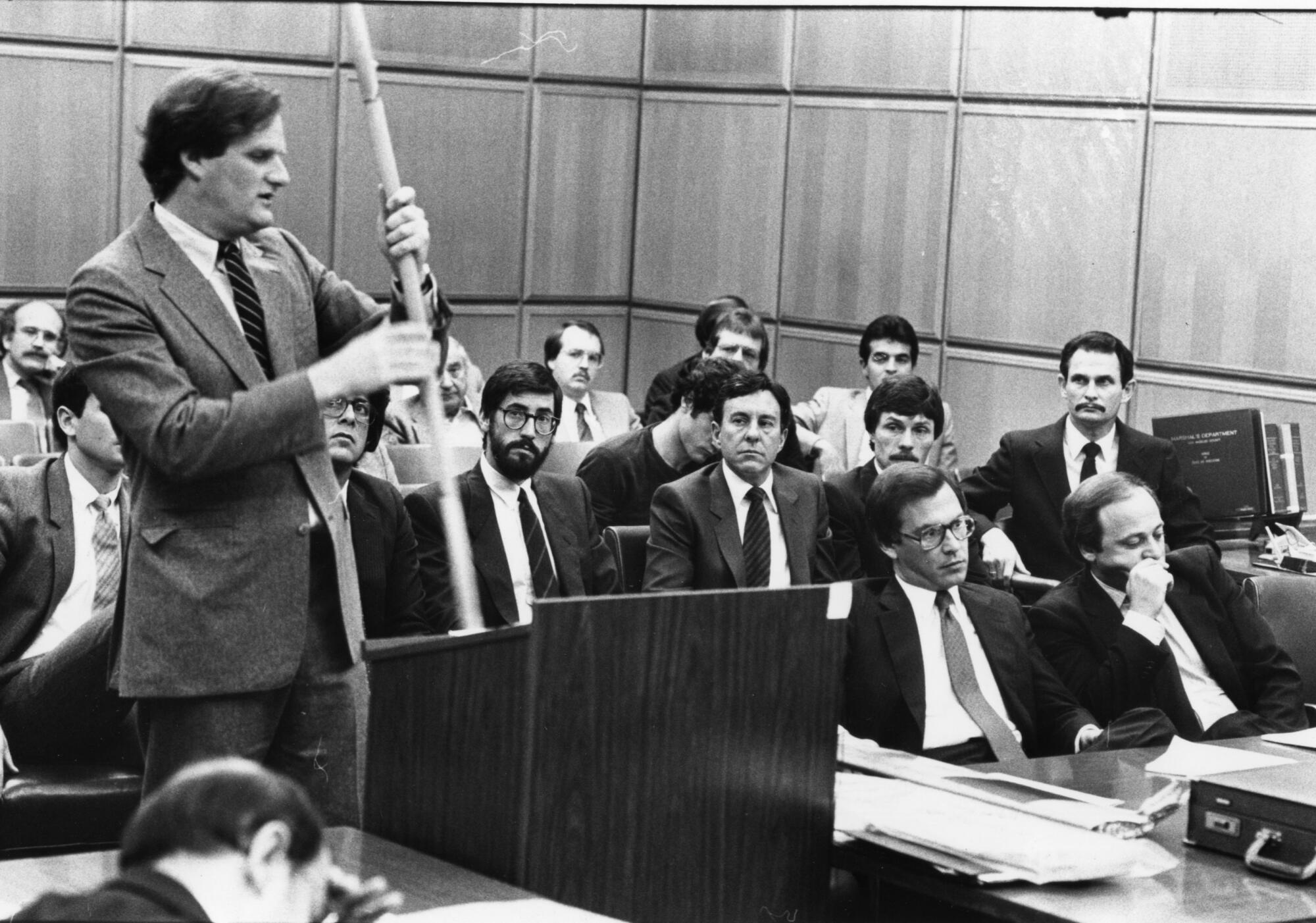

Then, Landis took his seat in a downtown L.A. courtroom as the first Hollywood director to face criminal charges for a death on set. The possible penalty was six years in prison. He and four others — his production manager, his associate producer, his special effects coordinator and the helicopter pilot — faced charges of involuntary manslaughter.

The prosecutor, the fiery and theatrical Lea D’Agostino, bragged that she had never lost a case. She liked her nickname, the Dragon Lady, because it connoted toughness.

She called Landis a “tyrannical dictator,” a reckless director who ignored common sense and sacrificed safety for realism in service of “a lousy motion picture.”

Sitting at the government table beside Sgt. Budds, D’Agostino was confident she could hold her own as the lone prosecutor against a seven-man team of aggressive defense attorneys. Among them was James Neal, the barrel-chested legend who had prosecuted the Watergate conspirators and Jimmy Hoffa, and who insisted to the “Twilight Zone” jurors:

“Not one of these gentlemen intended to hurt anyone. Not one of these gentlemen thought the scene as planned and rehearsed was dangerous. Not one of these gentlemen is guilty of criminal negligence.” He called the crash “unforeseen” and “unforeseeable.” If the helicopter had crashed a few feet away, he pointed out, Landis himself would be dead.

He and other defense attorneys directed blame to the effects man, James Camomile, who had been given immunity for his testimony and admitted that he had not looked up when he shot off the fatal fireball.

The most wrenching words came from the parents of the dead children, who said they had been misled about the danger.

“Did [associate producer George Folsey Jr.] or Mr. Landis or anyone else on that motion picture tell you that your daughter Renee was going to be filmed with explosives in close proximity to her?” the prosecutor asked.

“No,” testified Mark Chen, who had lost his only child.

“Did either Mr. Landis or Mr. Folsey or anyone else on that set, Mr. Chen, tell you that your daughter Renee was going to be filmed with a helicopter approximately 24 feet over her head?”

“No.”

He had agreed to let Renee do the picture, he said, so that “she would have a lot of memories” when she grew up.

My-Ca Le’s father, Daniel Le, who had been on the Indian Dunes set, said he heard someone ordering the helicopter to descend as the special effects went off: “Lower, lower.”

Having lived through the Vietnam War as a child, he said he was so startled by the on-set explosions that he dropped to the ground.

Jurors piled into a bus for a trip to the crash site, and to the Academy theater in Beverly Hills, where they watched the crash from six angles. (“A glamorous setting for a grim task,” one reporter called it.) Celebrities occasionally visited the courtroom, including Dan Aykroyd, a “Blues Brothers” and “Trading Places” star.

When defense attorneys presented their case, co-defendant Dorcey Wingo, who had piloted the downed chopper, stunned the courtroom when he seemed to suggest that Morrow bore some responsibility for the tragedy.

Five seconds had elapsed between the helicopter’s loss of control and the crash. “It distresses me to the max that he never looked up,” Wingo testified, which the prosecutor derided as “blaming the dead man.”

Landis took the stand in his own defense and quickly conceded that he had flouted the rules in hiring the children.

“We decided to break the law. We decided wrongly to violate the labor code.” Landis called it “a technical violation.”

The director denied joking to the cameraman that they might lose the helicopter. He denied that the parents were in the dark about the nature of the scene (he had told them personally, he said). He denied ever being warned that the filming of the fatal scene was dangerous. He denied any recollection of having ordered the helicopter to go “lower, lower.” At times, the director appeared to choke up.

“Would you like some Kleenex, sir?” D’Agostino mocked him.

Talking to reporters, she called it a calculated performance worthy of an Oscar.

“The whole world is lying, according to John Landis, except John Landis,” she said. “I find that somewhat incredible, and I’m assuming that the jurors will, too.”

She was badly mistaken about the jurors. After 10 months of trial and nine days of deliberations, all five defendants were acquitted on May 29, 1987. The jury forewoman echoed the defense’s main point, saying: “You don’t prosecute people for unforeseeable accidents.”

Landis, who declined to be interviewed for this story, told a reporter afterward that the prosecutor was “grotesque” and her case “completely dishonest.” “I feel that accident very strongly,” he said, adding that he was grateful for the jurors’ wisdom and comparing the outcome to a Frank Capra movie.

A year after his acquittal, jurors received invitations — along with their families — to a special preview screening of Landis’ new movie, the Eddie Murphy comedy “Coming to America.” Harland Braun, the acerbic attorney who represented one of the director’s co-defendants at trial, did not like how it looked.

“I wonder if he invited the parents of the children, because they were part of the case, too.”

The dejected prosecutor said she hoped, at least, that the case would deter future filmmakers from taking unnecessary risks. She believed the jury had been starstruck, a conclusion echoed nearly 40 years later by Budds, now 78. He thought it was unseemly, the way jurors embraced Landis and his wife after the verdict.

“They just identified with the whole Hollywood scene, and I think they missed the whole point about the responsibility to protect children,” Budds said. “It’s one thing if Vic Morrow chose to be under the helicopter, but to put little kids in that situation, it’s just unconscionable.”

In the aftermath of the deaths, the Directors Guild of America reprimanded Landis and tightened safety procedures.

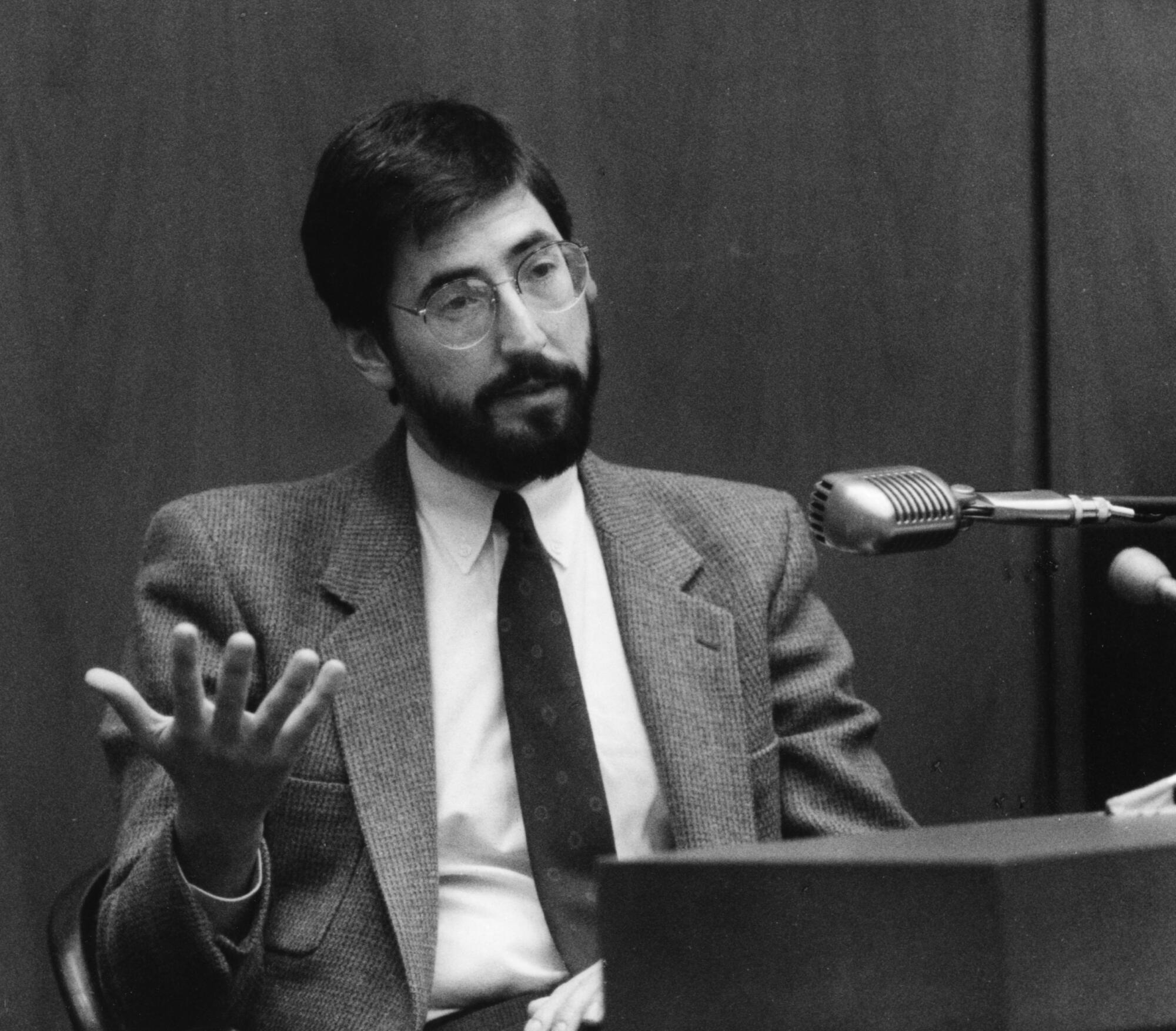

“I think it made people more conscious of safety concerns on film sets,” Stephen Farber, co-author with Marc Green of “Outrageous Conduct: Art, Ego, and the Twilight Zone Case,” said in a recent interview. The book argues that whatever the legal outcome, Landis bore moral responsibility for the tragedy.

“It was a wake-up call for many filmmakers of that period. I think they all were very much chastened by this case,” Farber said.

The length of the trial ensured that the terrible footage was constantly on the nightly news. It replayed endlessly, Morrow struggling through the water with a child under each arm, stumbling, righting himself, carrying them to the spot where they would all die behind the curtain of water.

On-set deaths, when they do occur, rarely dominate the news, with some exceptions, including the prop-gun deaths of Brandon Lee on “The Crow” in 1993 and Halyna Hutchins on “Rust” in 2021. A Los Angeles Times review found that at least 19 fatal injuries took place on film sets nationwide from 2010 to 2019.

The rise of computer-generated imagery makes it possible to achieve effects without actual explosions, so that now “you wouldn’t really have to blow up a whole village,” Farber said. But memories are short, and “I’m not convinced that something like this could not happen again.”

At Universal Studios, where Landis was sometimes spotted walking to his office in the 1990s, tram guides were forbidden from mentioning his name.

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact christopher.goffard@latimes.com

In the decades after the trial, when Landis gave interviews, he spoke in a booming, jovial voice and conveyed the impression of a man whose outsized self-confidence remained undimmed.

Did he escape accountability? Farber thinks the case ultimately hurt Landis’ viability as a big-time director. It made him easier not to hire, when he stopped creating hits.

Strangers made a point to remind the director of that night at Indian Dunes. Drew McWeeny, a screenwriter, once found himself on a TV set with Landis in Vancouver, where a local Teamster was reading “Outrageous Conduct” in conspicuous view of the director.

“Teamsters are on sets where they’re asked to do things they know they’re not supposed to do and told to take one for the team,” McWeeny said. “I think that for a lot of crew guys, Landis is the ultimate symbol of that.”

By McWeeny’s account, a frustrated Landis yelled at the Teamster, who was unimpressed and instead proffered the book with a question: Can you sign it?

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.