Judy Johnson’s stories were growing increasingly bizarre.

At first, she told police that a teacher had molested her 2-year-old son at the McMartin Preschool in Manhattan Beach. Soon, she said the abuse had involved altars, candles, a decapitated baby, an airplane flight and a figure called “the goat man.”

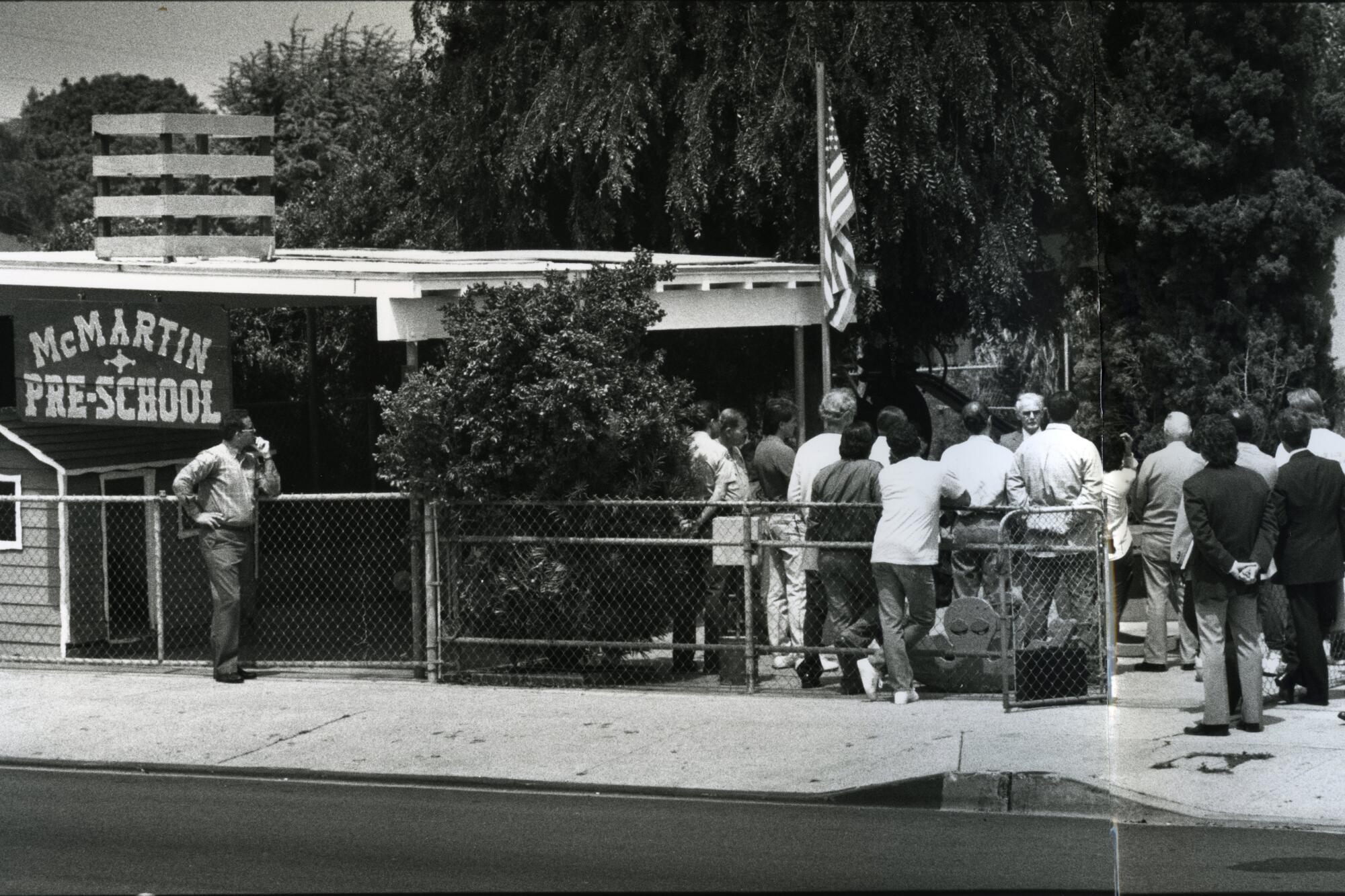

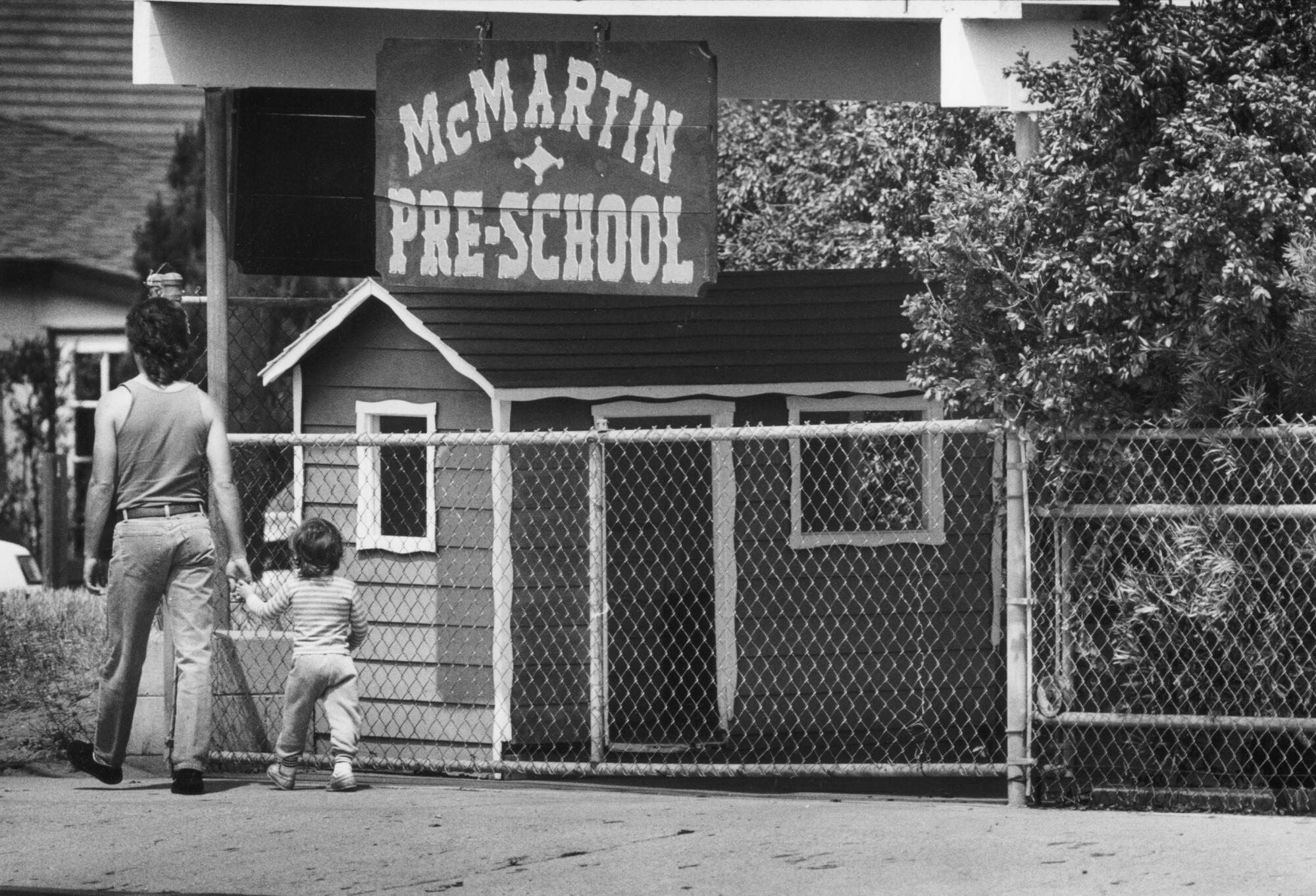

The family-run school had had an impeccable reputation, in an affluent South Bay beach town populated by professionals. Her claims sparked the largest sex-abuse case in American history, involving seven defendants, hundreds of children and more than 300 counts of child molestation and conspiracy.

It ended with zero convictions, and “McMartin” became a byword for social contagion, hysteria and the epic failure of trusted institutions: law enforcement, courts, the child-therapy establishment and the media.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

Even the former Los Angeles County district attorney who brought the case to trial — the longest in the annals of U.S. law — acknowledges it was a mistake, so poisoned was the evidence by suggestive interviewing techniques. Few of the now grown-up McMartin children have spoken publicly, but some have described the pressure to fabricate stories or disbelieve innocent memories in favor of traumatic ones.

In September 1983, spurred by Johnson’s complaint, local police arrested 25-year-old teacher Raymond Buckey, grandson of the preschool’s founder, and sent letters to 200 current and former McMartin parents.

“Please question your child to see if he or she has been a witness to any crime or if he or she has been a victim,” it read, including “oral sex, fondling of genitals, buttock, or chest area, and sodomy, possibly committed under the pretense of ‘taking the child’s temperature.’ Also, photos may have been taken of children without their clothing.”

Panic engulfed parents, and the district attorney’s office began referring families to Children’s Institute International, a Los Angeles therapy center, where social workers interviewed 400 children ranging in age from 4 to 10.

CII’s techniques were controversial. Kids were given anatomical dolls and encouraged to use puppets, such as Pac-Man, to communicate what was otherwise unspeakable.

They were presented with lurid and grotesque scenarios and told that their classmates had already divulged “yucky secrets.” When they insisted they were not victims, the social workers kept pressing.

The institute said 360 of the McMartin kids reported abuse. Children had spoken of being taken to secret rooms and tunnels, of being tied up, photographed naked and forced to play a game called “Naked Movie Star.” They spoke of mutilated animals and Satanic rites. One veteran child-abuse prosecutor articulated the article of faith underpinning the case: “No amount of questioning can make a child believe what he doesn’t believe.”

In March 1984, then-Dist. Atty. Robert Philibosian, in the thick of a campaign to keep his job, filed charges of child molestation against Buckey and six women — his sister, his mother, his 76-year-old grandmother, and three teachers. It was a conspiracy involving “millions” of items of child porn, a prosecutor alleged.

At the 19-month preliminary hearing, amid huge publicity, 14 former McMartin students testified. Some spoke of being forced to drink rabbit’s blood at the preschool, of being taken to a cemetery to watch a corpse dug up and mutilated. Asked to ID his supposed abusers, one child picked two men — the city attorney and action star Chuck Norris — out of a photo lineup.

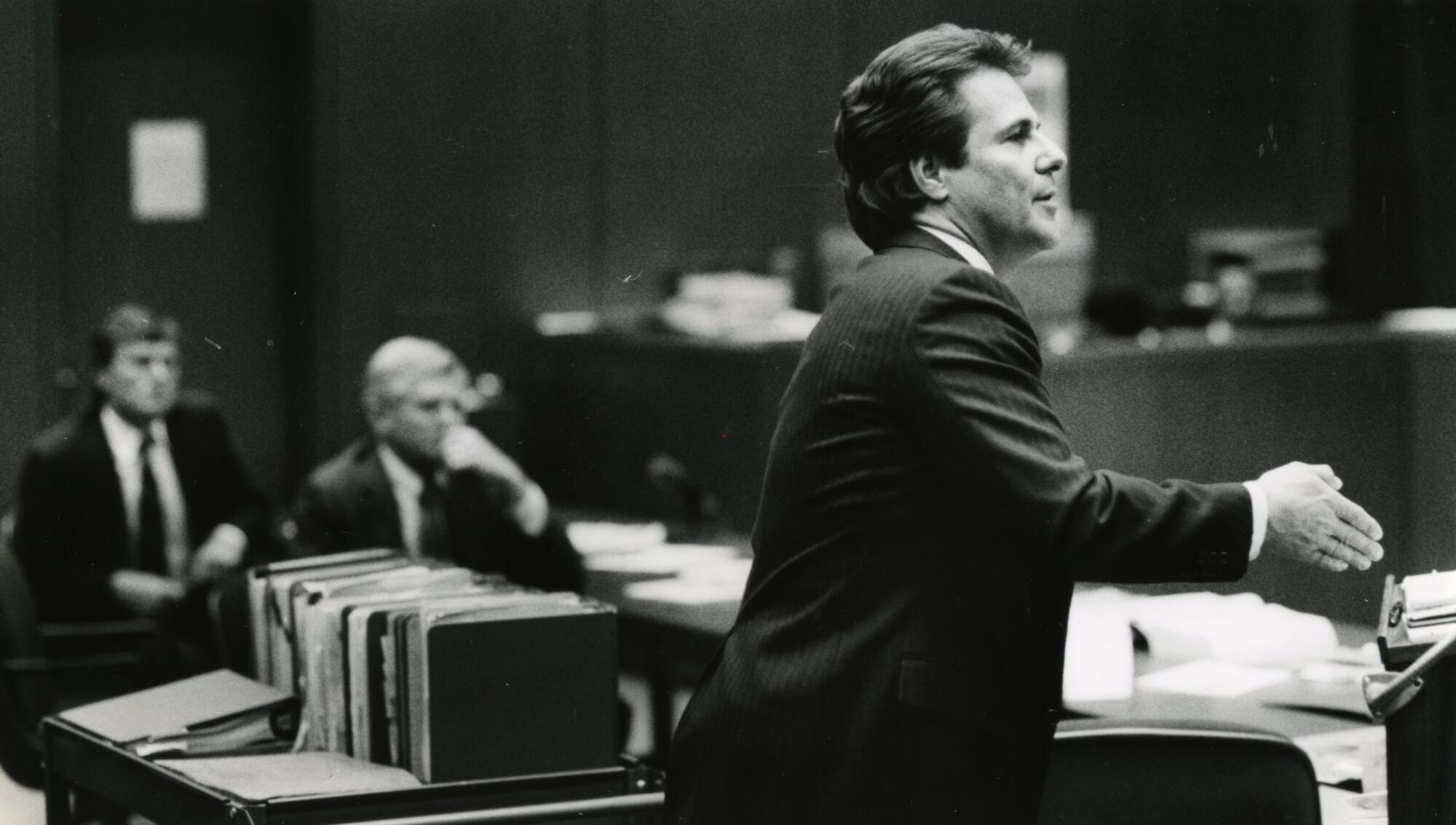

Danny Davis, the defense attorney who represented Raymond Buckey, cross-examined the children thoroughly and assailed the government’s scientific testimony, which relied on controversial “colposcopic evidence” — magnified scars alleged to show sexual abuse.

Davis endured death threats from people who believed he was defending monsters. “I was the face of it,” said Davis, now 78. “I was Darth Vader in their mind.”

He said Buckey, locked up without bail, would grind his teeth at night “down to the quick.”

A credulous media exacerbated the hysteria with “an echo chamber of horrors,” in the words of Times media critic David Shaw, who eviscerated the pack-journalism coverage. He itemized his own newspaper’s sins, which included the headline, “Brutality at McMartin’s School Revealed.”

“On the McMartin story, most of the media didn’t light a match within three miles of the D.A.’s feet during the first year or two of the case,” Shaw wrote.

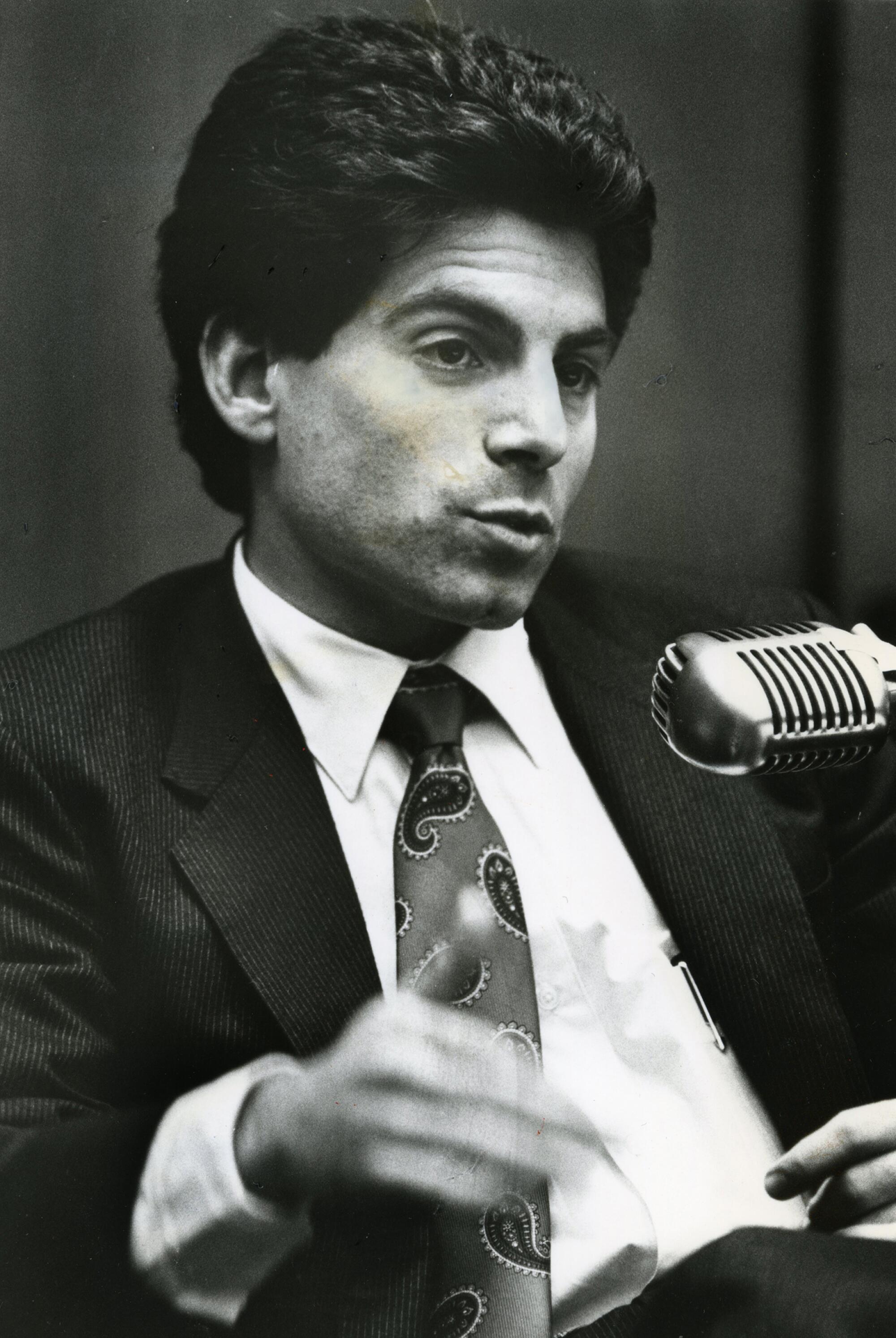

Glenn Stevens was one of the prosecutors. His belief in the case withered as the preliminary hearing progressed. Despite a massive search, not a single photograph turned up suggesting a child porn ring. Nor did evidence of trapdoors, subterranean rooms or tunnels at the school.

“I was out there with an entire investigative team from the Sheriff’s Department,” Stevens, now 71 and a real estate attorney in Beverly Hills, told The Times in a recent interview. “They had ground penetrating devices. They pulled up the floor, and there was a concrete slab on grade, and underneath it was dirt.”

The alleged abuse could not have plausibly occurred anywhere in the high-visibility school, he said. “It had no curtains on the windows. It was on the busiest street in Manhattan Beach. There are no locks on the gate, so anybody could have come in while this was happening.”

Then there were the tapes — hundreds of interviews conducted by Children’s Institute International. He said the D.A.’s team didn’t study them until the case was already moving through the courts, a process he described as “ass-backward.” Watching the tapes in chronological order, he was chilled. The accounts became wilder and more embellished, and what had seem like cross-corroboration now seemed a clear case of cross-contamination.

“When you start watching about 20 or 30 of these things, you really see what’s happening — they’re pulling information from particular victims and asking that stuff to subsequent victims.” The case “just ballooned, monstrously so.”

He said Judy Johnson, whose report about her son launched the case, showed signs of paranoia and mental instability and refused to let him interview her son.

To Stevens, a conspiracy among McMartin staff seemed increasingly remote. “How do you find seven people who have the same lustful interests and get them all to work at the same preschool? How is that even done?” Stevens said. “None of them had a record of any kind, even a traffic ticket.”

Stevens shared his misgivings with the media, embarrassing the office, and soon after resigned.

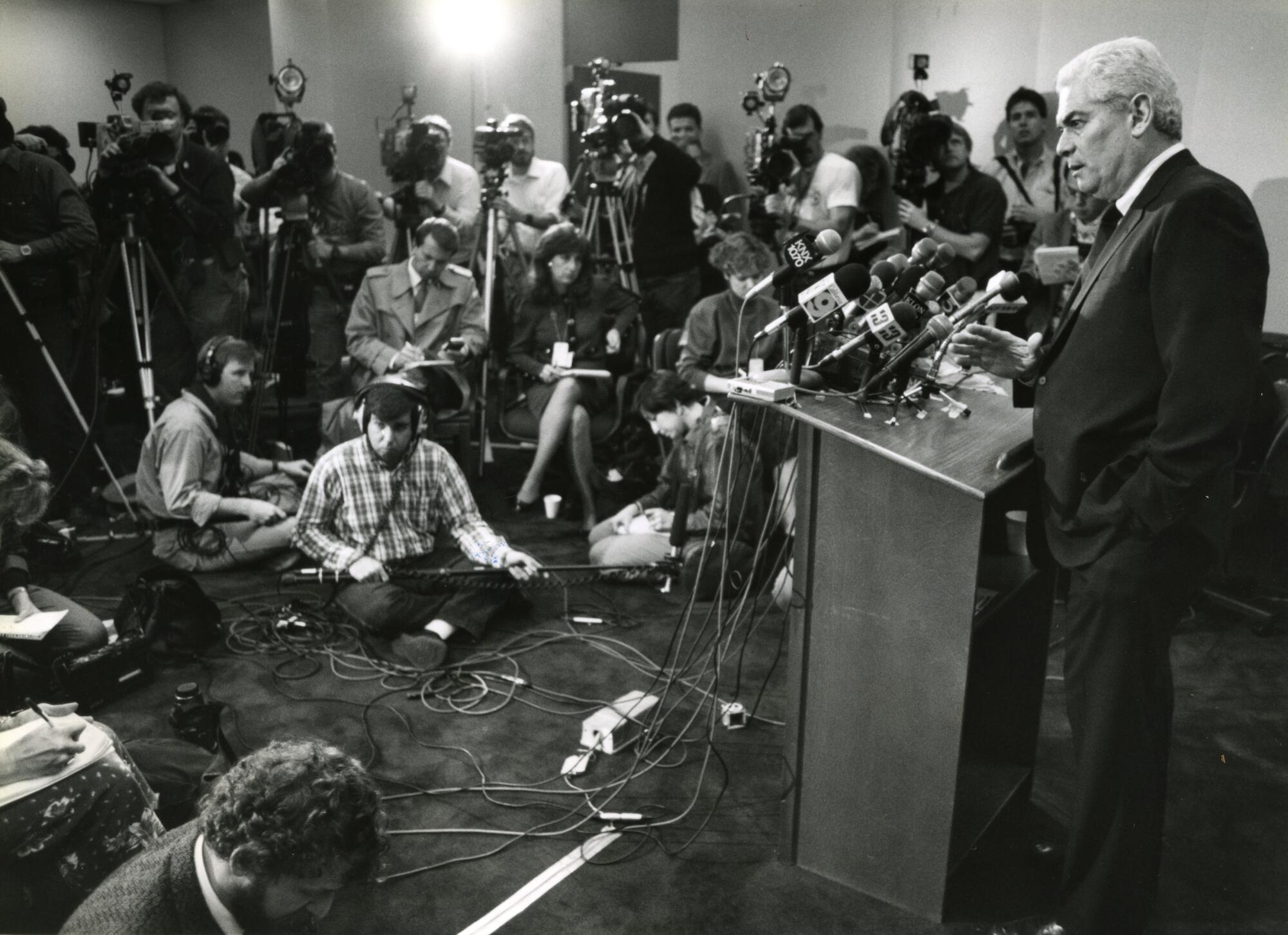

The same month, a judge decided there was enough evidence to send all seven defendants to trial. To the outrage of McMartin parents, the new D.A., Ira Reiner, dismissed charges against five of the defendants, calling the evidence against them “incredibly weak.”

But he allowed the case to proceed against Raymond Buckey and his mother Peggy Buckey, 59, a decision he now regrets.

Because the evidence had been corrupted beyond repair by Children’s Institute International, “I made a mistake by not dismissing against all the defendants,” Reiner told The Times recently. “They operated on a single principle, which was a fallacy: No child can make up such stories, therefore it was OK to lead them and push them. These kids believed what they said because it had been planted in their heads.”

For the record:

10:47 a.m. July 17, 2024An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to defense attorney Danny Davis as a prosecutor. Glenn Stevens was the prosecutor who was criticized for not disclosing questionable statements by Judy Johnson, the initial complainant in the McMartin sex-abuse case.

Defense attorneys questioned the mental stability of Judy Johnson, the initial complainant, and were furious that Stevens and other prosecutors hadn’t revealed some of her more unhinged statements. Among her allegations: an AWOL Marine had sodomized the family dog. She was found dead in December 1986, just before she was expected to testify, of an alcohol-related illness.

By the time the trial began in summer 1987, the news coverage had grown tougher-minded, but prosecutors did not relent. In their hands, Buckey’s quirks were presented as potentially sinister. A believer in pyramid energy, he slept with a big pyramid over his bed and sold pyramid-shaped hats at a UFO convention.

In January 1990, after a 30-month trial, the jury acquitted the Buckeys on 52 counts but deadlocked on 13 others. Raymond Buckey was retried, and after another deadlock, the D.A. finally dropped the case.

The estimated cost to taxpayers was $15 million. The Buckeys’ business had been destroyed, and the damage to their names was permanent. Raymond Buckey and his sister are still alive but through a friend declined to be interviewed.

Zoe Klemfuss, associate professor at UC Irvine who researches children’s eyewitness testimony, said the case spurred dramatic improvements in child-interviewing protocols. It is now widely accepted that “we can get kids to say all kinds of things that aren’t true just by showing them what we want them to say,” she said.

“As horrific as it was on so many fronts, the only silver lining to take from it is the research field really took off, and this fuel came literally from the McMartin case.”

Kevin Cody covered the case extensively for the community newspaper he publishes, the Easy Reader. He attended almost every day of trial and concluded the McMartins were innocent.

“They went through every minute of Raymond Buckey’s life. He was the perfect scapegoat,” Cody said. “Do not leave the impression that we’ll never really know. We do know. We know in hindsight the McMartin case was a fraud.”

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact christopher.goffard@latimes.com

The parents of the McMartin accusers were “doctors, lawyers, engineers,” he said, and they believed what the supposed experts were telling them.

Manhattan Beach is just 2½ miles long, and Cody still runs into some of the parents.

“Nobody talks about it at all,” he said. “The parents are just in a horrible position and so they just bury it.”

In the decades since, some former McMartin students have shed further light on the case. One accuser, Kyle Zirpolo, who was 8 when he spoke to CII therapists in 1984, said the stories he told about McMartin teachers — including the claim that kids were stripped and photographed — were not false memories but fabrications.

He hoped to win the love and attention of the adults around him, and he grasped what they wanted him to say.

“I would try to think of the worst thing possible that would be harmful to a child,” he told journalist Debbie Nathan. He conjured “satanic details” by imagining his own family church.

“From going to church, you know that God is good, and the devil is bad and has horns and is about evil and red and blood. I’d just throw a twist in there with Satan and devil worshiping.”

Maureen Flannigan, 50, a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker, calls herself a “unwitting victim.” She attended McMartin as a child and was interviewed by Kee MacFarlane, the CII social worker who became known as “the puppet lady” during the case.

Flannigan was given an Officer McGruff puppet and anatomic dolls. She told MacFarlane nothing bad had happened at the preschool, but her denials were interpreted as fear and repression.

“I was introduced to sexual concepts, not between a mom and a dad but between teachers and babies, basically,” Flannigan told The Times in a recent interview. “My 10-year-old brain exploded ... I knew early on if I didn’t give her what she wanted, I wasn’t getting out of that room.”

Despite her denials, she said, CII told her parents she had “most likely” been abused, and she came to believe that she had been, which haunted her for decades.

“They really did think they were doing the right thing. It was really under the banner of saving children.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.