By the time 38-year-old Caryl Chessman was executed on the morning of May 2, 1960, he had been on California’s death row for 12 years. His brooding, rough-hewn features were recognizable worldwide, his name a rallying cry from South America to the Vatican.

He was mid-century America’s foremost tough-hooligan intellectual, a high school dropout and autodidact who wrote and published four books while waiting to die. He bragged colorfully about his prolific crime sprees, but swore he was innocent of the charges that made him infamous.

He inspired literary admiration, hunger strikes, protest songs, diplomatic crises and a crisis of conscience for the state’s Catholic governor.

He is mostly forgotten today. But Chessman’s case dominated the debate about capital punishment for years. Apart from his skill as a writer, his gift for publicity and the length of his stay on death row — a record at the time — his case was unusual because he had not been convicted of murder or even charged with it.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

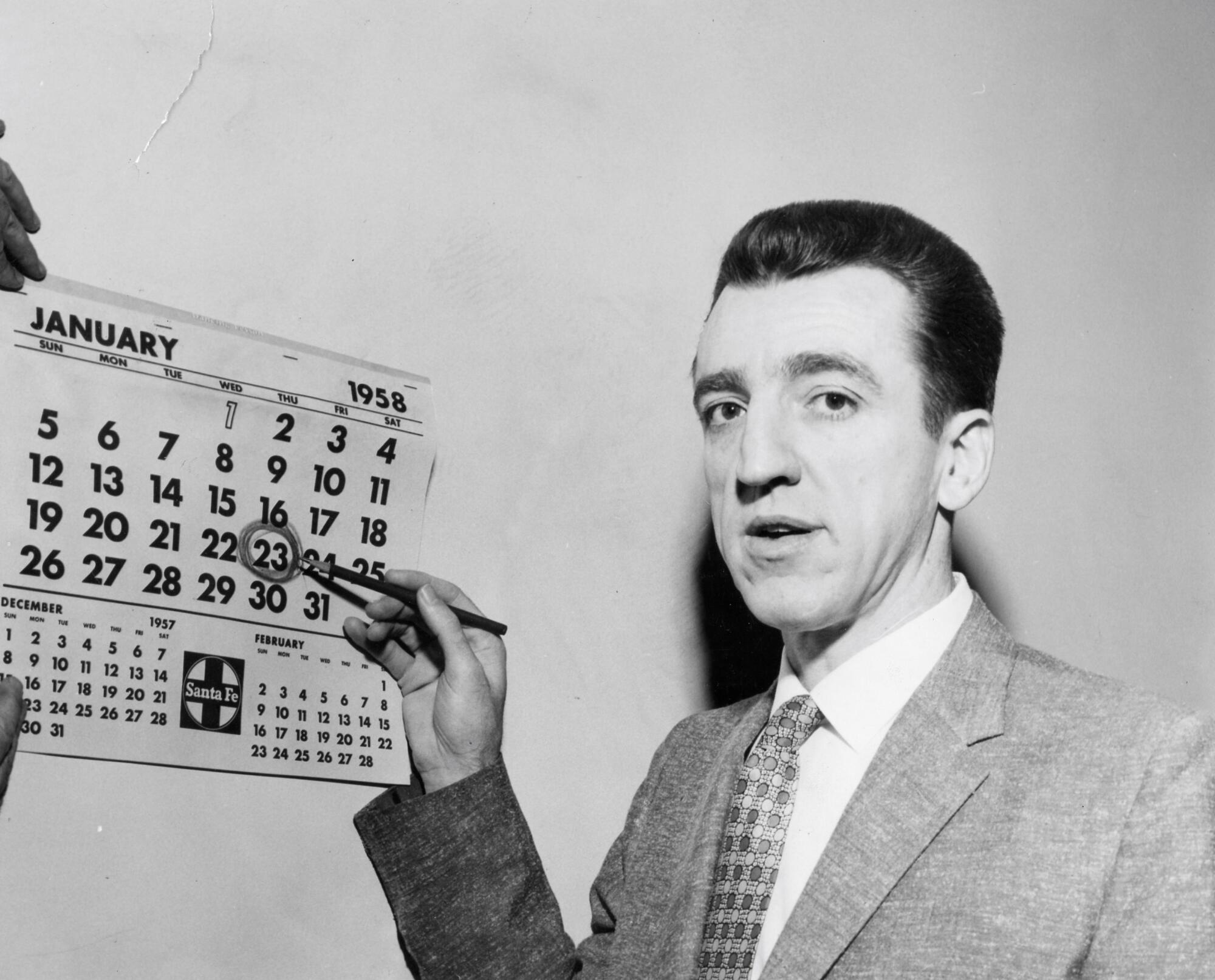

He became notorious, however, as the terror of lovers’ lanes. During a four-day stretch in late January 1948, the Red Light Bandit — so-called because his late-model Ford was equipped with a police-style flashing light to deceive victims — robbed couples at gunpoint in Malibu and Laurel Canyon, on hills and secluded roads above L.A. and Pasadena.

In one attack, the gunman forced a woman to accompany him to his car — a distance of 22 feet made arduous, a prosecutor would say, by the effects of polio — and forced her to perform oral sex. Two nights later, the gunman abducted a 17-year-old girl, drove her around the city for hours, and again demanded oral sex. Those two incidents would bring charges under the state’s Little Lindbergh Law, which permitted the death penalty in kidnapping with bodily injury.

After a high-speed chase, police caught Chessman at Sixth Street and Vermont Avenue in a stolen Ford linked to a Redondo Beach stickup. During interrogation, Chessman implicated himself in the bandit’s crimes, though he claimed police beat the confession out of him.

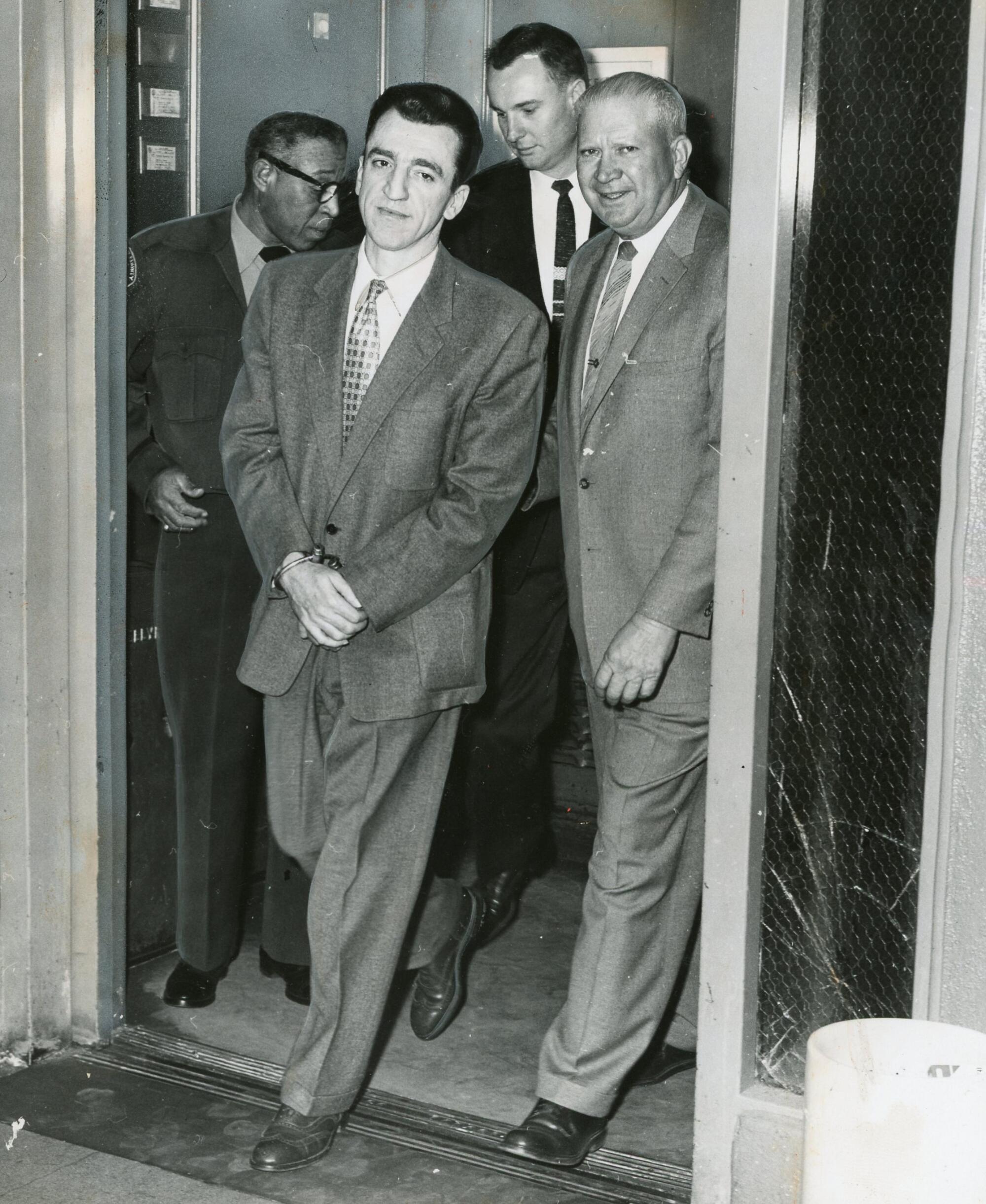

Disastrously for Chessman, whose arrogance and hunger for the spotlight were among his most striking traits, he insisted on acting as his own attorney. He cross-examined the sexual assault victims, who identified him as their attacker. The teenage girl looked at him directly and said, “I know it was you.”

“He liked to boast about being a great criminal, but great criminals don’t keep getting caught,” Theodore Hamm, who wrote a book about Chessman, told The Times in a recent interview. “He thought he was the smartest guy in the room and he could outwit any prosecutor and win over the jury. It obviously didn’t work out in his favor.”

Jurors convicted him of 17 counts for a month-long crime spree. He was 26 years old, and smiling defiantly, when the judge handed down two death sentences. His 12-year legal battle to avoid San Quentin’s gas chamber — what he called “that ugly green room” — attracted worldwide attention, as did his prison writings.

His 1954 memoir, “Cell 2455, Death Row: A Condemned Man’s Own Story,” became a bestseller.

He described his face, with its battered nose and large features, as one “that has seen too much, a young-old face, scarred by violence… a predatory face that seemingly has found its rightful place in the gallery of the doomed.”

Born in Michigan and raised in Glendale by devout Baptists, he became conscious of “the shame and the degradation” of poverty when his father’s business ventures flopped.

He wrote of a childhood in which he learned to scorn society and its codes, concluding that “you got away with anything you were smart enough to get away with.” He spent years in juvenile detention, reform school and jail.

He loved “the game of cops and robbers,” he recounted, and became an expert prevaricator. Arrested for theft on his 17th birthday, he told police “one glib lie after another” and developed “a fool-proof technique: tell near-truths, half-truths, but never the whole truth.”

He described himself as having been “a grinning, brooding young criminal psychopath in defiantly willing bondage to his psychopathy.” With “hate and guile the tools of his trade,” he held up bordellos, liquor stores and gas stations. In a gunfight with police, he yelled, “Come on, you dirty bastards, let’s play!”

His long criminal record was never in dispute, but it’s easy to suspect he embellished some of his outlaw exploits. His stories had a self-dramatizing flair. He understood the tug of crime for the attention-hungry — and society’s weakness for outlaw heroes.

“All you have to do is be a violent, robbing, murderous bastard and your fame is assured,” he wrote. “One of the peculiarities of squares is their screwy propensity to glorify rogues and scoundrels.”

In some circles, his death row writing was greeted with rapture. It was a “sparkling contribution” to criminology, according to the New York Times, and evidence of “salvation of the self,” as Partisan Review magazine put it.

“He impressed the New York intellectuals,” Hamm said. In a postwar period teeming with optimism about the possibilities of reform, “he came to stand for a rehabilitated prisoner, and the evidence of his rehabilitation was his articulate explanation of things that wove in pop psychology about reform.”

Eleanor Roosevelt, Ray Bradbury and Aldous Huxley signed pleas to spare Chessman. Petitions poured into the office of Gov. Edmund “Pat” Brown, a Democrat who believed Chessman guilty but abhorred the death penalty on religious grounds. In 1959, he denied Chessman clemency, saying he’d shown no contrition but rather “steadfast arrogance and contempt for society and its laws.”

Chessman made the cover of Time, and around the world, from the Vatican newspaper to the Daily Mail in London, editorials weighed in on his side.

Ronnie Hawkins recorded a protest song, “The Ballad of Caryl Chessman,” with lyrics that captured the sentiment among many sympathizers: What they’re saying may be true, but what good would killin’ him do? Let him live, let him live, let him live. I’m not sayin’ forget or forgive…If he’s guilty of his crime, keep him in jail a long, long time, but let him live, let him live, let him live…

The Los Angeles Times was not among the sympathetic voices. An editorial denounced the “save-Chessman madness,” arguing that the real outrages were the drawn-out legal maneuvering and political weakness that had delayed his execution.

“Grinning, arrogant, sharp-witted — and alive — Chessman, committer of indescribable crimes, is a heavy reproach to the state’s conscience,” The Times argued, saying his supporters were ignorant of the gravity of his crimes “because the newspapers dare not publish the horrible details.”

The U.S. State Department warned Brown that Chessman’s execution might inflame protesters during an upcoming trip President Eisenhower planned in Uruguay, where the prisoner was a cause célèbre. And Brown got a call from his 21-year-old son, Jerry, a recent seminarian and future governor, who pleaded with his father to spare Chessman’s life.

The governor ordered a reprieve, but when he asked lawmakers for a death penalty moratorium, they refused. Anti-Chessman crowds burned Brown in effigy and booed him and his family in public.

Prison officials tried to muzzle Chessman, but he kept writing and had pages smuggled out. Eight times, he was assigned dates with the green room, and eight times he won delays.

In the end, Brown claimed he was powerless to stop the execution, because the state Supreme Court had ruled against Chessman.

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact christopher.goffard@latimes.com

Until his death, Chessman denied he was the Red Light Bandit. He suggested he knew who the “real” Bandit was, but refused to say. One of his last comments was, “I hope my fate has contributed something toward ending capital punishment.”

The circumstances of his execution gave further ammunition to critics who saw the system as capricious and absurd. That day, Chessman’s lawyers had persuaded a judge to issue a brief stay, but the judge’s secretary misdialed the prison to relay the news — and by the time the call went through, Chessman was dead.

Chessman wanted his remains deposited alongside his parents’, but Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale refused on the grounds that he had been “unrepentant.”

The case galvanized opponents of the death penalty, and reformers used it to press for modified kidnapping statutes. California executed another inmate under the Little Lindberg Law in 1961, the last for a nonlethal crime, and the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty 11 years later (though it was reinstated). In 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a moratorium on executions in California.

The case haunted Brown’s political career. When Ronald Reagan defeated him as governor, Brown knew his opposition to the death penalty played no small role. Brown believed Chessman a nasty and arrogant man, yet his failure to do more to save him would prove a source of deep regret.

There were political calculations “for an elected official with programs he hoped to implement for the common good,” Brown would say, decades later. “I firmly believe all that. I also believe that I should have found a way to spare Chessman’s life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.