Looking to discover L.A.’s Mexican history? Check out these 10 places

- Share via

The history of Los Angeles is complicated, and there’s no better example of this than Olvera Street. Located downtown in the L.A. Plaza Historic District, the popular marketplace is lined with Mexican restaurants, stores and kiosks selling everything from T-shirts to pottery to statues of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

For decades, many have believed that Olvera Street was the historic Mexican center of Los Angeles. In reality, it was created in 1930 by Northern California transplant Christine Sterling, who fell in love with a romanticized Old Mexico filled with strolling guitar players in sombreros and women in colorful peasant dresses.

The city’s first Mexican immigrants came to L.A. from the states of Sinaloa and Sonora in Mexico during the Gold Rush and settled in an area that became known as Sonora Town. It wasn’t located on Olvera Street but several blocks away, in what is now Chinatown.

What happened to Sonora Town? Like so many Latino neighborhoods, transportation and rising real estate prices pushed residents to other parts of L.A. when the Southern Pacific Railroad put its depot nearby.

Historic monuments all over the city and county tell a story of Los Angeles from the people who settled here, not necessarily those who existed here until their land was taken away.

We can’t forget that California belonged to Mexico until it became a state in 1850 after the Mexican-American War. For centuries before that, California was home to hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people until the Spanish arrived in 1769 and wiped out many of them through violence, enslavement and disease. The Indigenous communities that survived faced another horrific challenge when in 1851, California’s first governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, declared war against them “... until the Indian race becomes extinct …” resulting in more than 100,000 more deaths.

There’s so much hidden history to be found. So where can you go in Los Angeles to uncover these stories? Here are 10 places to learn or think about L.A.’s Mexican history.

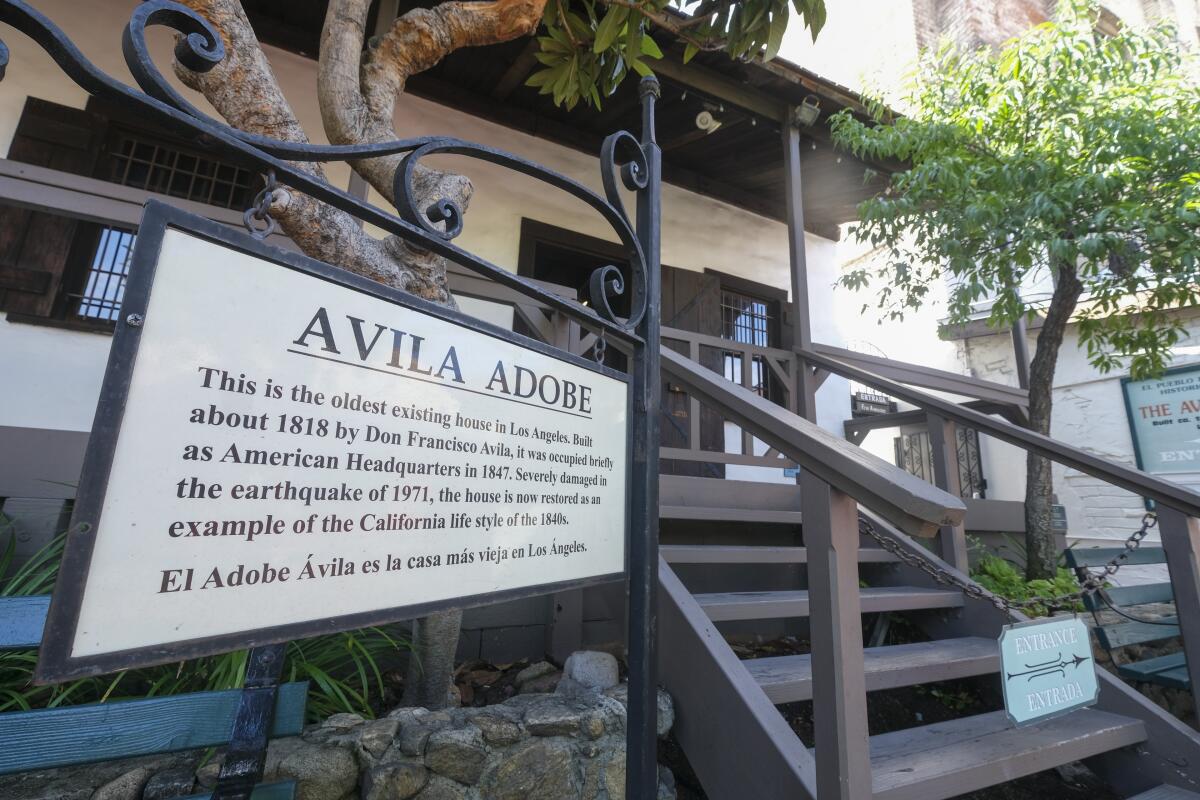

Ávila Adobe

Pico House & Los Pobladores

Alta California’s last governor, Pío Pico, opened Pico House in 1870. Pico, who was of Spanish, African and Indigenous Mexican descent, was one of the most powerful men of the 19th century and had a major L.A. thoroughfare named after him.

If it’s surprising that one of California’s richest and most influential 19th century men was Afro-Mexican in a time of great racial unrest, you may want to visit the Los Pobladores plaque on the southwest side of the Plaza. It honors the 11 families (44 adults and children) from Sinaloa and Sonora that the Spanish government persuaded to travel 1,000 miles to settle in the new pueblo of Los Angeles in 1781. Nearly half of the adults identified as Black or mixed race.

La Placita (La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Ángeles)

The Spanish Bishop of Monterey, Calif., took the martyred Saint Vibiana’s remains to Los Angeles, made her the patron saint of L.A. and built a grand cathedral in her honor. The original cathedral was damaged in the Northridge earthquake and the Catholic Church tried to demolish it in 1996. The L.A. Conservancy sued to stop the demolition and won. The original cathedral was renovated to its former glory and is now Redbird restaurant and the stunning Vibiana event space.

Ft. Moore Pioneer Memorial

Boyle Hotel/Mariachi Plaza

Kuruvungna Village Springs

Bust of Arcadia Bandini Stearns de Baker

'The Ink Well' rock

Campo de Cahuenga Memorial Park

Dominguez Rancho Adobe Museum

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.