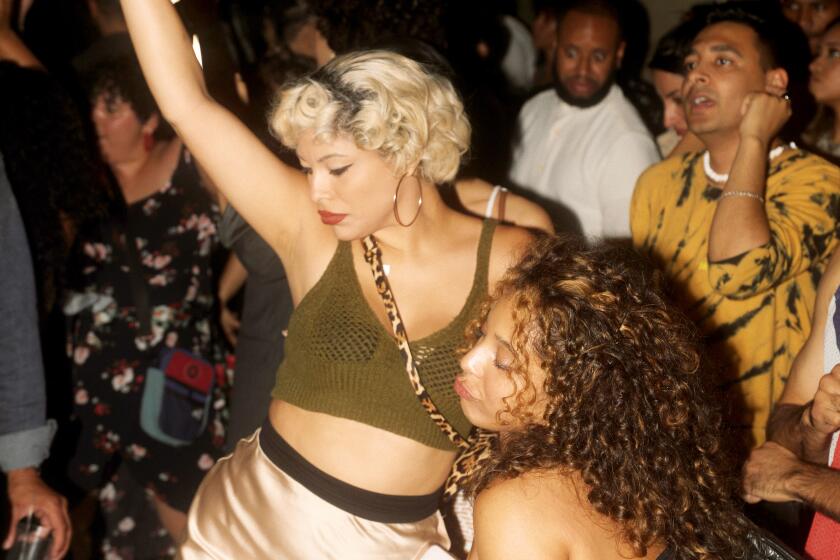

I met Jenny when I began my research on modern Oaxacan sexualities in the summer of 2017 at Club Tempo. At the time, I was an introverted PhD candidate in the City of Angels with no informants to guide me through my research quest until my gay brother introduced me to Jenny — a gender nonconforming diva who took me under her red phoenix wings. Jenny introduced me to the ambient — the social scene that Mexican queer folk at Club Tempo use to construct their lives.

Jenny is a Malandrina, the kind of woman who listens to Jenni Rivera’s Mi Vida Loca. She is a vestida, a woman born biologically male, and a regular at Club Tempo. One time she confessed to me, “Amiguis, yo voy a morir en Tempo” (“Friend, I will die in Tempo”).

To learn more about Club Tempo, read this feature story by Frank Rojas from October 2022.

On one of my usual trips to the club, I went to the vaquero dance floor, located on the first floor, to the right of the front door. On this floor, the music consists of banda and norteñas. Many of the songs come from central and northern Mexico. As usual, I came dressed in a vaquero, cowboy attire, with a black Tejana hat and boots. The floor was filled with dancing men dressed in cowboy hats, striped shirts and boots.

It’s clear there’s a desire for Caribbean culture in L.A., as more and more Caribbean Latines make their way to the West Coast.

I went to the left corner of the bar, walking by seven cowboys who were drinking a tecate cahuama — a two-liter beer. Jenny stood inclined on the bar, wearing a blue and black dress with red lipstick. Her hair was often as glamorous as that of Jenni Rivera, the late Mexican singer of regional Mexican music. In her choice of makeup, she liked big lashes and lots of mascara that made her look like a soap opera actress. I walked up to Jenny and hugged her. She whispered in my ear, “Amiguis, con quien veniste?” (“Friend, who did you come with?”).

Jenny is a vestida and also a Zapoteca, a member of the American Indian people living in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. She was born in a town on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the state of Oaxaca. She came to the United States when she was a boy — a teenager. She told me she crossed the border undocumented and according to her, she made the coyote (smuggler) fall in love with her.

Club Tempo in Hollywood caters to the queer vaquero community. It’s where they can show off their pride in both who they are and where they come from.

The first city she arrived in was Fresno, where she lived with her uncle and aunt. They kicked her out of their house when they found out she was a gay boy and was flirting with a neighbor. After struggling with homelessness, she eventually became a hairstylist. She ran her hair salon until city inspections closed it for not having a license, but Jenny attributed the salon’s closure to the stylists who were jealous of her success.

While in Fresno, she made trips to Los Angeles where she fell in love with Club Tempo and has not stopped going there ever since. She was 18 back then. She told me that Tempo used to be a club for real vaqueros but that it was not like that anymore, now that the majority of the patrons are feminine.

When hanging out with Jenny in Tempo, I came to know her friends, Edgar, Junior, Jorge and a blue-eyed man that Jenny called la Minaj. Jenny also introduced me to her friend Oscar, a handsome and smiling gay man from Shihuahua (Chihuahua, Mexico) who grew up in El Paso.

The organization’s founders saw a need for an LGBTQ+ youth mentorship program, so they set out to create one where Latinos and others could feel accepted.

Since Jenny had been going to Tempo for about a decade, she’d made many friends. There were the drag queen performers like Maritza, who was one of the most famous drag queens, the transgender women that hang out on the outdoor patio of Tempo’s second floor and the bouncers who flirted with her once in a while. In addition to friends, Jenny also had enemies. I remember Jenny was involved in a fight with a man who was known to be very good at dancing to banda. She also fought with another vestida. Jenny did not tell me the details about that fight, but the rumor was that this person got engaged with a man to get papeles, meaning to get a green card.

I was seduced by Club Tempo’s music, performances, stylish outfits, and most importantly, stories of migrations and painful love affairs. Within months, I could not have enough of Tempo. Jenny’s thrilling way of seeing life was not easy to ignore. It was inspiring.

When it was time to leave Los Angeles’ ambiente to continue my research in Oaxaca, Jenny organized a final night out to Tempo. After we said goodbye, I drove up north from Los Angeles to Oxnard, where I grew up after arriving from Oaxaca in 2003. I danced by myself in the middle of the agricultural fields.

Noé López has a PhD from the University of Texas at Austin and works in finance and digital banking. His writing and research focus on the socioeconomic development of his homeland, Oaxaca. @noelpzoax

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.