- Share via

I saw something on the internet (where I live) the other day, something that got my mind going.

It was a photograph of a poncho featuring a “chibi Guadalupe.”

For the uninitiated, “chibi” is a Japanese style of caricature that features cute, exaggerated features such as small, chubby bodies and oversize heads. This made me want to explore the many representations of the Virgen de Guadalupe in Mexican and Chicano culture, and how her constantly shifting image has provided the glue that holds our unstable identity project together.

For Chicanos in particular, the sweet treat has become a mascot. But what is it about the concha that has elicited such fanfare?

Celebrated Mexican poet Octavio Paz once said that “the Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments and defeats, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery.” That sounds about right. Our history with La Virgencita stretches all the way back to the founding of the nation of Mexico, with some claiming it goes back even further.

The famed origin story of the iconic image goes something like this. In 1531, an Indigenous Chichimeca peasant named Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin was chosen by the Virgin Mary to deliver a message to the bishop to build a chapel in her honor. The bishop demanded a sign, and so the Virgin instructed Juan Diego to collect some flowers on a hill, place them in his tilma (a mantle or cloak), and bring them to the bishop. When he did so, the flowers dropped to the floor, and Guadalupe’s image was emblazoned on the mantle. It’s sort of like the world’s greatest outfit reveal, for fellow “Drag Race” fans.

Juan Diego would go on to be canonized as a saint (whose name I took at my confirmation ceremony), and the image would go on to become an instantly recognizable icon of Mexican culture. She became a symbol of revolution in 1810 when she was brandished on the banners of Padre Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla as he led the nation in the war for independence from Spain. In 1859, when Mexico’s first Indigenous president, Benito Juarez, implemented separation of church and state, he left the Day of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Dec. 12, intact as a religious holiday.

She also was an important image for the Chicano movement starting in the 1940s and for farmworkers in the ‘60s. In both cases, her image was used as an expression of revolution and ethnic unity in the face of oppression, much as she was in the 1850s. She even features heavily in art about crossing the border, as seen in retablo-style works meant to either request divine protection or thank a heavenly figure for allowing loved ones safe passage into the United States.

But while she’s often been at the forefront of movements seeking to upend the status quo, she is also, of course, a symbol of the Catholic Church and a tangible product of the colonization of what we call the Americas. How can the image of one woman hold so many paradoxes, and why has her power as a symbol so totally captivated us?

All of this will get back to the star of the show, the chibi Guadalupe, I promise. But first, it’s important to understand that Mexicans and Chicanos see themselves as paradoxical. “¡Viva México, hijos de la chingada!” goes a popular cry, and it’s a declaration of pride in being the offspring of a wound, the sons of a woman who was forcibly ripped open. To quote Paz again, “In this shout we condemn our origins and deny our hybridism.”

For Paz, and for many Mexicans, including those in diaspora, there is a persistent anxiety rooted in ethnic identity. This isn’t unique to Mexicans at all. Most nation-states are deeply concerned with questions about ethnic coherence. How do you make a group of people who speak different dialects and who see themselves as culturally distinct consent to the requisite fictions of statecraft? How, in other words, do you make a large body of individuals come to see themselves as united under a national project?

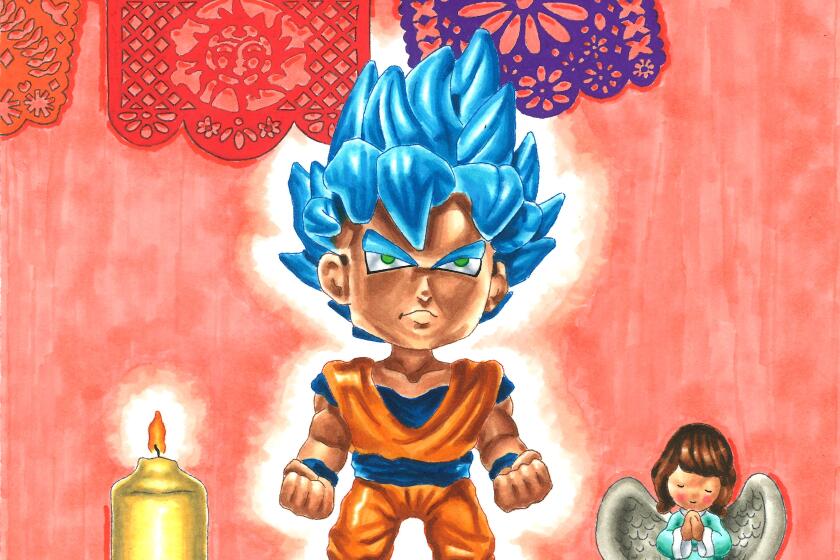

Legendary manga artist Akira Toriyama died Friday. Among his work was the ‘Dragon Ball’ series, which has found mass success with Latino and Latin American audiences.

Imagery plays a huge role on that front. The power of imagery can resolve paradoxes that might otherwise be sources of confusion or complaint. The Catholic Church itself has long relied on images to this end, using the cross to represent the mystery of the Trinity, and using marble and gold and towering spires to signal its power to worshipers of a religion that preaches austerity. For it to work, there has to be a great degree of flexibility to the symbol, which exists in the material world, but mostly in the ether of ideas, where it can take on whatever shape it needs to in order to perpetuate itself.

Even though the original tilma is allegedly on display in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on the Hill of Tepeyac in Mexico City, there is no one true image of La Virgencita. She exists as a symbol of staunch devotion to the church, of the Mexican Revolution, of Chicanos looking to identify themselves with Mexico, of both the colonization that devastated Indigenous populations who still struggle to this day, and of syncretism in the form of her association with Tonantzin, a goddess of the Anahuac peoples. She speaks to the pride, guilt, confusion and clarity that color the Mexican experience.

All of this came to my mind when I saw chibi Guadalupe, which immediately made me laugh. It reminded me a bit of my previous column about Mexicans loving Goku from “Dragon Ball Z,” and there’s definitely another point to be made here about the fascinating relationship between Latin America and Japan. But what I love about this image, specifically, is that, well, it’s a bit blasphemous, isn’t it? I can’t imagine the Catholic Church ever condoning such a thing. But for centuries now, Mexicans have been doing things with the symbol of Guadalupe that the Catholic Church wouldn’t officially approve of. It’s not unprecedented in the least.

Chibi Guadalupe, to me, represents yet another mask of Guadalupe, one of many she has worn over the years. They all say something different, and they all speak to different cultural attitudes and shifts in attitudes toward aesthetics, nationalism and religion. Chibi Guadalupe comes to us in a globalized world that borrows freely from the visual traditions of a country on the other side of the planet for the purposes of commercialism. One imagines this poncho resting alongside many purses featuring Frida Kahlo’s face and colorful luchador masks.

It’s both entertaining and fascinating to be reminded that even symbols as towering and enduring as Our Lady of Guadalupe are subject to reinterpretation, and, indeed, that’s why such symbols exist in the first place. They are made to withstand the test of time, to be able to adapt to the ebbs and flows of modernity so that they might continue to provide an answer, however incomplete it might be upon closer investigation, to that age-old question, “Who are we?”

And, I mean, mira, que cute!

John Paul Brammer is a columnist, author, illustrator and content creator based in Brooklyn, N.Y. He is the author of ”Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons,” based on his successful advice column. He has written for outlets like the Guardian, NBC News and the Washington Post. He will write a weekly essay for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.