For many children of immigrants, going home — whether for the holidays or as a quick stop on your way home from work to pick up the caldito de res that your mom lovingly packaged in an emptied Cool Whip container — often comes with some added chores.

Resetting the router, calling the pharmacy or, in my mom’s case, restoring the Candy Crush points she fears she lost in an iPhone update. But as our parents get older, the chores become a means of addressing their traumas.

Over the holidays, TikTok was filled with posts of children of immigrants cleaning out their parents’ cluttered homes. In one video showing an overstuffed closet and someone placing a Hannah Montana CD in a storage bin, the text onscreen reads, “That part of the holidays when you have to force your parents to declutter the house & work through their scarcity mindset.”

Melissa Barrera showed solidarity with Palestinians. Hollywood showed its persistent double standard

Barrera’s firing is a sad reminder of how historically marginalized groups, like Latinas, are forced to walk a tightrope when advocating for social causes, and of how fragile “representation” is in Hollywood.

In another, various piles of objects are seen collected on tables or stuffed into bags. The onscreen text reads: “As a child of immigrant parents who hoard every single thing, I became minimalist…I help my parents reduce their clutter because I don’t want to deal with it all in the future. And I want them to see how much better life is with less.”

A scarcity mindset is the anxiety one feels when you believe the resources you have, whether money, opportunities or objects, are limited. They’ll disappear, and you won’t be able to replace them. The anxiety can be so real that we take on more work than we can handle or accept things we may not need because maybe one day we will.

It manifests in different ways for people, depending on the circumstances of their lives and experiences.

These TikToks feel all too familiar for other children of immigrants, who see how the scarcity mindset can cause their parents to obsessively hang on to or collect stuff, or how the immigrant mentality of saving things that can be reused (see: Country Crock container full of beans in your mom’s freezer) leads to a mountain of mess.

“There’s some deep, deep, trauma about things and recuerdos and making good use of whatever,” said Genaro Ulloa, an educator based in L.A. whose family lives in El Centro. “To take that away from somebody that has, in their mind, worked so hard to collect and maintain all of these things, regardless of the value, regardless of the sentiment — it really strikes a nerve.”

For Ulloa, his mother struggles the most with attachment to objects, but his dad “also has got a lot of s—.” The family moved into their home in 1995, but there are still boxes they’ve yet to unpack. As they’ve accumulated things over the years, the family house has become overrun with boxes.

There are over 2,000 variations of pan dulce, but the soft bread bun topped with sweet cookie-like dough is popular for a reason.

Ulloa explained that it becomes a bigger issue around the holidays when his parents prepare to host a big family Christmas party.

“She has this checklist. ‘I have so many things for you to do,’” he explained. “But she has to do them with me, and she has to take her time to clean, to go through every box and assign where they should go. And so like for me, my mom just needs me to be with her there to keep her company, to keep her calm, to let her do her process.

“I never considered it my place to have that judgment, or that push to want my mom to change,” he added. “All of my other siblings get really frustrated with her, and she ends up crying. My role is just to keep my mom happy.”

That resonates with Amanda, an L.A. actress who didn’t want her last name used to protect her family’s privacy. She was helping her parents temporarily move out of their home in Chula Vista to a condo in Tijuana, her dad’s hometown, where they’d be living while their house was being remodeled. “My mom had to look at every little thing that we’re all packing,” she said. “So it was six of us packing stuff, but it took so long because she had to revise every little thing.”

On the day they had to be out of the house and have it cleared out, Amanda’s mom had a breakdown. “She’s like, ‘Everybody grab everything you see!’” said Amanda. “And she’s just grabbing all the trash we left. I’m like, ‘Mami, give me this. Leave this.’ She’s grabbing a broken hanger. I’m like, ‘This is just trash.’ She was freaking out. She really didn’t want to leave anything.”

Amanda recalls hearing stories from her mom, who grew up extremely poor in the Philippines, about not owning any shoes and having to walk barefoot everywhere. As a result, her mom has held onto things and takes anything free that’s offered to her.

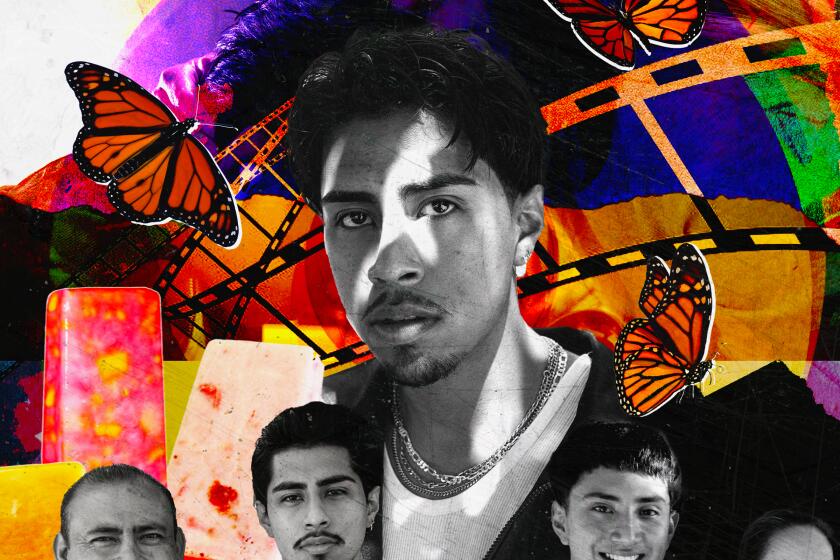

A DACA recipient from a humble background, Ezekiel Pacheco’s story bears a striking resemblance to that of Nico, his character in ‘At the Gates.’

“It’s beautiful to see the way that she tends to her stuff like her treasure, and then it goes from treasuring something to hoarding,” said Amanda, who admits she’s taken after her mom in her love of “junk” and clutter.

Both Ulloa and Amanda try to be present as a support system for their moms and not force them to unpack their behavior.

In doing so, they carry an emotional burden.

“There’s so many things that I wish that I could just let go for her, but these things are archived within her own body,” said Amanda. “I feel like I see my mother as a baby in these moments where all you can do is hug her and tell her it’s gonna be OK.”

Evelyn Alvarez is a caregiver for her mother and an ambassador for the Alzheimer’s Assn. in the Bronx. She and her family had to declutter her mother’s home, but in their case, it was “a little bit easier because my mom has dementia so she didn’t have the emotional attachment.”

As she has navigated cleaning out her mom’s home, managing elder care and helping others as they do the same, Alvarez encourages a compassion-forward approach as well as starting the process early on, before your parents get too old or possibly ill.

“[It’s about] being conscientious about what it means to get rid of something that people really worked hard to obtain, even if it’s not good,” she said. “And the emotional relationships that people have with their little items, and being creative about the ways that you can save things that are important.”

Steve Corona is a Los Angeles skater who has gone viral on Instagram thanks to videos that show him dressed in what he calls his ‘Pati-Charro’ aesthetic.

Alvarez says the holidays are a good, albeit extra stressful, time to talk about what’s gonna happen as parents get older. That includes what will be done with their things because each person has an entire lifetime’s worth of objects that may be meaningful to them. She recommends taking photos of items of deep personal connection and saving them in albums, so parents can still see them even after the objects are gone.

Alex Zaragoza is a television writer and journalist covering culture and identity. Her work has appeared in Vice, NPR, O Magazine and Rolling Stone. She’s written on the series “Primo” and “Lopez v. Lopez.” She writes weekly for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.