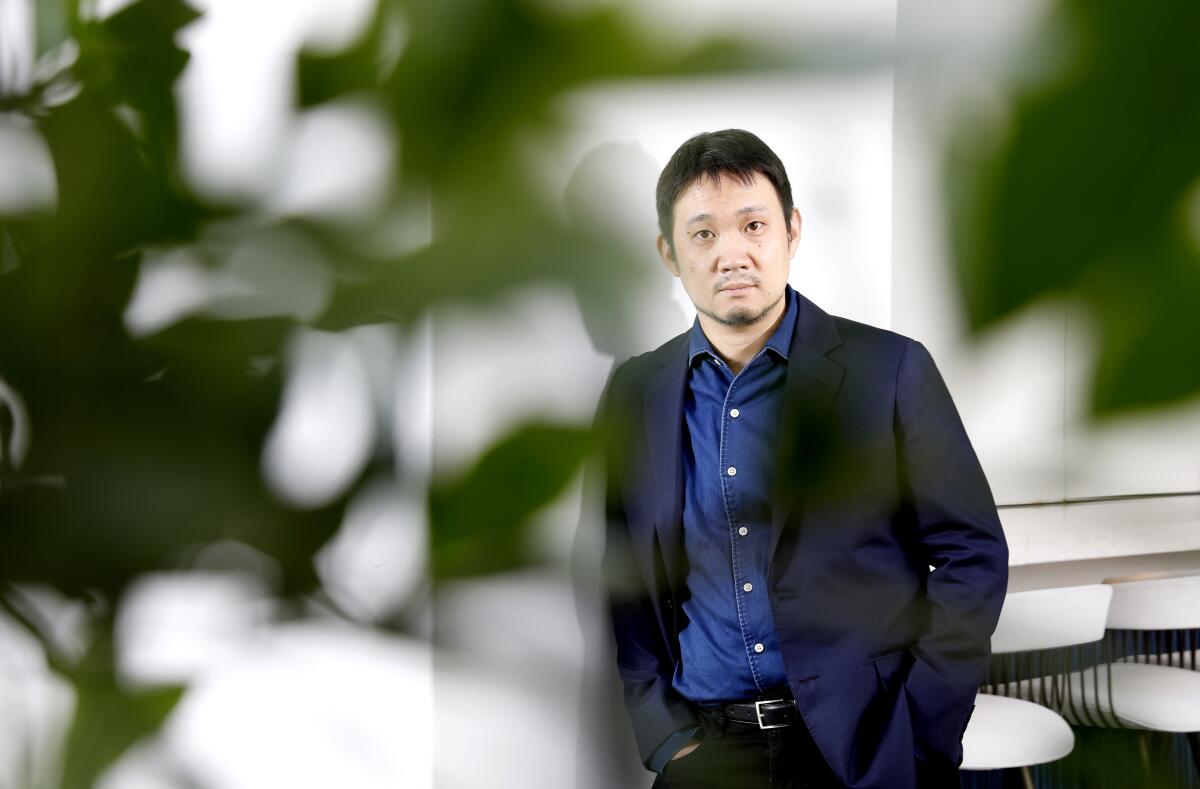

How Ryûsuke Hamaguchi adapted three stories and a play to create ‘Drive My Car’

Japanese auteur Ryûsuke Hamaguchi adapted a roughly 40-page Haruki Murakami short story into a fully realized, seamless three-hour film, “Drive My Car.” But it was much more involved than that: He actually took material from three Murakami stories, and within that adaptation, he included significant passages of Anton Chekhov‘s stage classic “Uncle Vanya” — in multiple languages. And he accomplished all of that while retaining Murakami’s themes and expanding far beyond where the author left his characters.

“The short story didn’t really have a conclusive ending; it was sort of midway through,” said Hamaguchi, through an interpreter. “From the audience perspective, that’s something they might be dissatisfied with. I had to think of ‘What were the characters’ issues, and how were they going to be solved?’ I thought the most legitimate way to do it would be to use other stories from this collection ... there were common themes running through them.”

“Drive My Car,” nominated for four Oscars, including best picture, director and adapted screenplay, could as easily have been called “Men Without Women,” after the book from which Hamaguchi mined the three tales. The central relationship, between actor-director Kafuku (played by Hidetoshi Nishijima in the film) and laconic driver Misaki (a perfectly cast Tôko Miura), and Kafuku’s wife’s infidelities — including with a man Kafuku came to know, Takatsuki — come from the collection’s first story, “Drive My Car.” But the most unforgettable aspects of Kafuku’s wife, Oto, come from another, unrelated story: “Scheherazade,” in which a woman having an almost regimented affair tells her lover fascinating stories of her past following their sexual encounters. In the film, that basic scenario exists with the stories being inventions, not memories. A third entry in the collection, “Kino,” contributes more subtly, with its decisive violence and main character’s catharsis.

Hamaguchi said, “The character Kino, in the short story, is also cheated on by his wife, and there are things that he should be noticing that he doesn’t. In the same way, there are things Kafuku should have realized, so I used ‘Kino’ to show the place where he should be getting to. Also, in regards to the violent nature of Takatsuki [in the film], this was something depicted in ‘Kino’ that influenced the character of Takatsuki.”

That’s quite a bit of surgery on material by one of the world’s foremost authors of fiction. Hamaguchi was undaunted.

In the Murakami story, Kafuku is a somewhat fading stage actor in a performance of “Uncle Vanya”; the discovery of his glaucoma requires the use of a hired driver, a young woman named Misaki. In the car, Kafuku drills his lines with a cassette tape of the other characters’ dialogue. Apart from a brief, quoted passage, the Chekhov barely appears in Murakami’s pages. In Hamaguchi’s film, it’s a major presence: The artistically formidable Kafuku is directing the play; his “Vanya” is cast with actors from several different Asian countries, speaking the dialogue in their own languages (one uses sign language).

Hamaguchi said, “I had a friend who had gone to France and performed with a multilingual acting troupe. That was extremely interesting. Even if it’s in just one language you don’t speak — let’s say for me, it’s in English — I’m not going to get everything, but I’m going to base my understanding on nuances, emotions, things like that. [The actors] are going to have this very intense concentration to be in tune with the other people.”

This device suits his and Murakami’s theme of deeper understanding, realizing one didn’t know another as one thought. But Hamaguchi also saw parallels between the play and his characters. Vanya is envious and obsessed with what might have been; Kafuku is likewise unable to free himself from the past and looks jealously upon Takatsuki, whom he has cast in “Vanya” despite knowing of the affair.

“I was surprised by the amazing [correlation] between Vanya’s character and Kafuku’s character. The lines spoken by Vanya really match up with the feelings Kafuku has. Because I wasn’t using [Murakami’s devices of] flashback and inner monologue, this would also help express those things.”

He also saw “parallels between Misaki and Sonya [Vanya’s niece, a practical person to whom Vanya listens]. The driver Misaki is able to guide Kafuku to solutions to ease his burden. This is similar to the relationship of Sonya and Vanya. There was the solution of being able to live on, to move forward with your life.

“The theme of how those left behind, those surviving, go on with their lives — this is definitely in the film. You have to move on, or it won’t end. I thought, how can the audience come to think that Kafuku will be OK, to think, ‘He’ll be all right’? That’s how it turned out this way.”

One of Hamaguchi’s subtler changes is also one of the most significant. The film adds the wrinkle that the voice on the cassette with which Kafuku runs lines belongs to his wife, Oto.

“After she dies, he’s continuing this conversation with her even though she’s not physically there anymore,” said Hamaguchi. “Of course, it’s a [set] conversation; he’s not gaining any information about the things he wants to know about her, her secrets. It’s a safe way for him to interact with her. It’s also a way to show how he’s still so caught up with his wife.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.