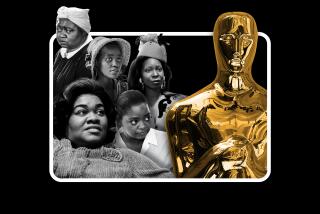

Commentary: It’s not just the Oscars that fail Black women. It’s the entire awards ecosystem

As in the years of “Selma,” “One Night in Miami” and “Mudbound” before it, Tuesday’s Oscar nominations, an hour filled with elation for many, brought disappointment to Black women.

It’s not the first time the Academy Awards have been scrutinized for their shortcomings on diversity: The organization supposedly went through a collective soul-searching after 2015, when April Reign made #OscarsSoWhite a cultural touchstone. The resulting multiyear effort to diversify the academy’s voting body has produced seismic wins such as “Moonlight” and “Parasite” taking the prize for best picture. For Black women, little has changed. In the entire history of the Oscars, the only Black woman ever to win lead actress is still Halle Berry. Still no Black woman has ever received a directing nomination. (Six Black men have been nominated; still none has won). And still only one film directed by a Black woman — Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” — has been bestowed with a best picture nomination.

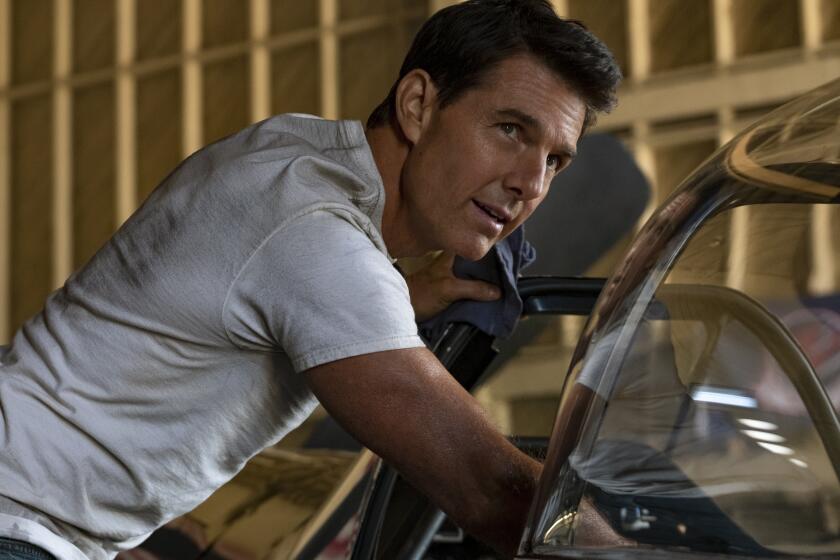

Oscar nominations bring surprises, including Andrea Riseborough, Ana de Armas and Brian Tyree Henry; and snubs of Danielle Deadwyler and Viola Davis.

This year, that bleak track record became more glaring: Alice Diop’s critical darling “Saint Omer,” France’s submission for international film, didn’t make it over the finish line. Gina Prince-Bythewood’s “The Woman King” didn’t appear in any categories, not even the technical areas where many pundits expected the historical epic to perform well. Both Viola Davis (“The Woman King”) and Danielle Deadwyler (“Till”) were shut out of lead actress after months at the front of the race. (Angela Bassett did score a supporting actress nomination for “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.”)

Meanwhile, Andrea Riseborough, spurred by a last-second, grass-roots campaign, which witnessed celebrities publicly supporting her case, received a surprise lead actress nod for the little-seen indie “To Leslie.”

Although it’s easy to point a finger at Riseborough for taking a slot from Black women, broken systems persist when we focus our ire on individuals. Rather than interrogating Riseborough’s specific campaign — for a harrowing performance, I might add — one should ask a different question: What does it say that the Black women who did everything the institution asks of them — luxury dinners, private academy screenings, meet-and-greets, splashy television spots and magazine profiles — are ignored when someone who did everything outside of the system is rewarded?

Before #OscarsSoWhite, the (flawed) prevailing logic held that there simply weren’t enough Black women making movies. In the director field, the rise of DuVernay, Regina King, Dee Rees, Nia DaCosta, Chinonye Chukwu, Janicza Bravo, Mati Diop and many more has obliterated that canard. In addition to Davis and Deadwyler, Keke Palmer, Zendaya, Dominique Fishback, Taylor Russell and more have contributed to an explosion of Black women actresses in contemporary cinema. Black women have always created. But their heightened prominence in today’s Hollywood means the excuses for not highlighting them ring especially false.

Why does the inequality persist? Maybe voters aren’t making these films a priority on their dense screener pile. Or maybe they’re not understanding the cultural specificity of the work. Even with the changes, the academy is still a majority white organization, after all.

Then there are the all-important precursors before the Oscars. The Directors Guild of America, for instance, has never nominated a Black woman director in its main feature category, and a miss in the primary feature category is a near-death blow to any director’s chances with the academy. Mati Diop, Alice Diop, Melina Matsoukas, Radha Blank and Regina King did receive nods for first-time feature, but in the entire history of the award, instituted in 2015, Jordan Peele is the only nominee for that prize to be nominated for a directing Oscar.

Best picture is the only Oscars category that uses a preferential ballot, where voters rank all 10 nominees. Here’s how our critic would rank them.

While Black actresses have fared better at finding nods in precursors like the Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild and BAFTAs, wins have proved harder to come by. In the last 20 years only one Black woman took home lead actress at the Globes (Andra Day), only one for SAG (Viola Davis, twice) and none at the BAFTAs.

Even major critics organizations struggle with Black women: The National Society of Film Critics and the New York and Los Angeles film critics associations have never awarded a Black woman as director. The last time the National Society of Film Critics bestowed lead actress to a Black woman occurred in 1972 (Cicely Tyson in “Sounder”). It’s happened twice with NYFCC (Regina Hall for “Support the Girls” and Lupita Nyong’o in “Us”). It’s never happened for LAFCA.

So the problem isn’t solely the academy’s. Nor does it trace back to one white actress’ awards campaign. No, such prejudice has deeper roots, reaching into fields outside of film: Black women are often stereotyped as aggressive, loud and unprofessional. They’re critiqued for their hair, nails and fashion. They’re hypersexualized. They’re less likely to be hired, and even less likely to be promoted.

If a director like Prince-Bythewood, a creative with decades of critically lauded films, can’t break through with a studio-backed crowd-pleaser like “The Woman King” — the kind of film the academy has awarded in the past, like “Gladiator” and “Braveheart” — then what hope does that leave for others? If Davis, a performer who might be the Meryl Streep of her generation, can be honored with an Oscar only by running supporting rather than lead, as she did with “Fences,” then who will break through? Why is the work of Black women continually seen as lesser?

As a critic, I find that many well-meaning white folks assume the problem continues because of racists. But if the issues are systemic, then surely those who think of themselves as on the “right” side are not as well-meaning as they believe. During the summer of 2020, many white people in the entertainment industry pledged — as with #OscarsSoWhite — to be better. As normalcy returned those promises faded, and fast.

Hollywood continues to opt for the bare minimum when it comes diversity: window dressing on its blind spots, as it were. And unsurprisingly, these efforts have mostly fallen short of sustainable change. Few have a vested interest in remaking the system they call home, the one that affords them advantages, the one they came up in themselves.

The actor received a groundswell of support from A-listers for her role in the otherwise little seen “To Leslie.”

“For how does one overthrow, change or even challenge a system,” asks bell hooks, “that you have been taught to admire, to love, to believe in?”

After Black women lost on Oscar nominations morning, the awards apparatus deserves a prize of its own: least likely to learn from its mistakes.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.