Review: From the Nazis to RBG, how Richard Wagner changed the world

On the Shelf

Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music

By Alex Ross

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 784 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

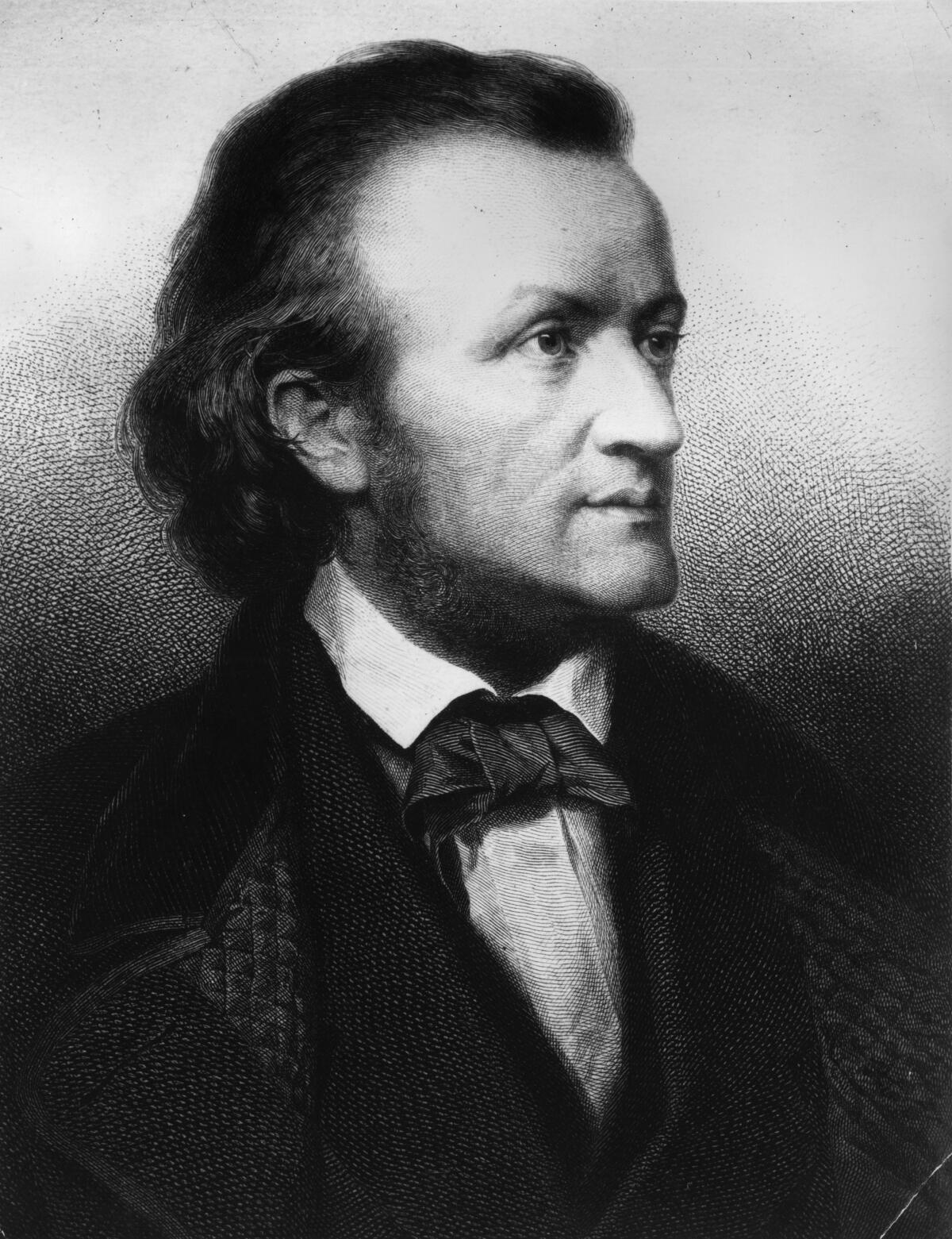

You cannot escape Richard Wagner.

If this review has reached you, anywhere in the world and by whatever means, you have already had your life affected in some way by a 19th-century megalomaniacal composer of mythic German operas. It doesn’t matter that classical turns you off and you wouldn’t be caught dead (or asleep) at the opera. It doesn’t matter if you have canceled Wagner and every domineering dead, white, European male thing about him. That hasn’t stopped the “Lohengrin” Bridal Chorus from bringing near-universal joy at weddings.

New Yorker music critic Alex Ross’ magnificent new book, “Wagnerism,” presents this particular “ism” as an overwhelming force containing, like atomic energy, constructive and destructive powers. Underscoring Wagner’s pervasive influence on culture and society, Ross makes his subject less Wagner himself — although he has plenty to say about the music and the problematical man — than the way we absorb ideas and attitudes, how they can grow into cancers or panaceas.

The novelist Thomas Mann, who had an epic love/hate relationship with Wagner, called the composer the “greatest talent in the entire history of art.” There is no question that he offered something for everybody. Ross points out that in the early days of the Weimar Republic, Wagnerites could be found among the Communists just as among the proto-Nazis. Despite Wagner’s poisonous anti-Semitism, Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, spent many an evening at performances of “Tannhäuser.” W.E.B. Du Bois, the pioneering African American author and activist, was another Wagnerite. Go figure, and that is exactly what Ross does in this very big and heroically even-handed book.

Wagner, Ross asserts from the start, was the progenitor of “the cultural and political unconscious of modernity.” By “conjuring legends in the dark,” he anticipated the advent of cinema. An incomparable publicity hound, he gave us the modern notion of self-promotion, turning provincial Bayreuth, where he created Germany’s most exclusive festival, into a Wagner company town. An equal-opportunity influencer, Wagner made a mark on the modern novel, modern poetry, modern architecture, modern visual art, modern philosophy, modern psychology, modern warfare, modern genocide and, of course, modern music.

The great, pugnacious critic Stanley Crouch died last week. Rock critic Robert Christgau, who edited his reviews at the Village Voice, remembers him.

Ross demonstrates how the city you live in, the government you live under, the culture you consume (high and low) and the way you consume it very likely has Wagner molecules in its DNA. The concepts of total theater, surrealism and stream-of-consciousness could all be traced to Wagner, along with any number of religious cults. The seductive eroticism of his music was an aphrodisiac for French and Italian decadents. The masterful triumphalism in the operas gave erstwhile losers, like the young painter Adolf Hitler, ideas. Wagner was called the Sorcerer of Bayreuth for a reason.

Most famously, Wagner was a mythmaker who remains relevant for our time. Discussing Wagner’s four-part “Ring” cycle, Ross notes that the story of the fatal ring “can always speak to the latest soul-stealing technological miracle.” The 20th century’s two greatest mythologists, Claude Levi-Strauss and Joseph Campbell, credited the operas for the birth of their professions.

The “Ring” operas went on to vivify everything from the Nazi obsession with the Aryan superman to the blockbuster superhero of our own day. Yet the men in the “Ring” are all duplicitous or clueless, and by the end, as the opera-loving Ruth Bader Ginsburg was said to have pointed out, it took a woman to save the world. As director Francesca Zambello recently recalled in the New York Times, “Götterdämmerung,” the finale of the tetralogy, was the feminist, liberal, Jewish Supreme Court justice’s favorite opera.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

Wagnerism, as a movement, had strong roots in the fandom of Friedrich Nietzsche. “Every fiber, every nerve in me is quivering,” Ross quotes the philosopher in response to hearing Wagner’s music. Like many other relationships with Wagner, then and now, Nietzsche’s went sour. But pro or con, the fixation remained. Throwing off the Wagner yoke only affirms the power of Wagnerism.

Ross focuses much of his attention on Germany, Vienna, Paris, London, Milan, St. Petersburg and Hollywood. French Wagnérisme funneled through Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Cézanne, Gauguin, Debussy. British Royals fetishized Wagner; Bloomsbury and James Joyce came under his spell; Shaw was the perfect Wagnerite, taking a socialist swirl through “The Ring.”

Every culture has its own issues with Wagner, and Ross’ even hand is especially impressive when taking on the Big One. His explication of Hitler’s rise and the legacy of Wagner’s anti-Semitism is a moving lamentation, yet it lays bare the contradictions. Wagner was misread, misinterpreted. He had been a youthful revolutionary and anarchist who became increasingly reactionary as his renown — and his insatiable needs for luxury — grew. But he remained opposed to standing armies and war. He spewed venom all the while considering himself a man of the people. For all his anti-Semitism, he entrusted his final opera, the Christian-themed “Parsifal,” to a Jewish conductor.

In the end, the inconsistencies are what made Wagner matter, and what make Ross today’s perfect Wagnerite. The operas, often stemming from his insecurities, are among art’s greatest psychological studies in what makes us, with our angels and devils, tick. On that subject, Ross is most persuasive in his close readings of canonic post-Wagnerian literature, particularly Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past,” Joyce’s “Ulysses,” Virginia Woolf’s “The Waves” and the novels of Mann.

Wagnerism in the U.S. is the most remarkable phenomenon of all. It reached Nebraska through Willa Cather. Lincoln Kirstein co-founded New York City Ballet with a dash of Wagnerism on his mind. Upton Sinclair got a helping hand from Wagnerism in his mission to save the free press and democracy. Mark Twain parodied Bayreuth but he was not immune to Wagner’s allure.

Underscoring Richard Wagner’s influence on film music

Never short of contradictions, Hollywood is a Wagnerian story in and of itself. Wagner’s music was in films from the start — at least 1,000 to date. “The Ride of the Valkyries” notoriously animated Klansmen in their raid during early screenings of the racist silent classic “The Birth of a Nation,” and made its equally famous ironic reprise 64 years later in a helicopter raid on Vietnam in “Apocalypse Now.”

The first sound film, a year before “The Jazz Singer,” opened with the New York Philharmonic playing the overture to “Tannhäuser.” The émigré founding fathers of the film soundtrack happened to be trained in Wagnerian techniques in Vienna and Berlin, and their use of themes, or leitmotifs, set the stage for symphonic film music to this day. John Williams’ scores to the very Wagnerian “Star Wars” series are a prime example. Hollywood has surely spread Wagner furthest of all.

Finishing the appropriately all-consuming “Wagnerism,” a reader can easily come to fear there is no stopping Wagner. Much progressive music created in the aftermath of World War II was necessarily anti-Wagnerian. On the West Coast, a musical ethos, established by Henry Cowell and carried on by Harry Partch, John Cage and Lou Harrison, looked much farther East and was notably disinterested in Wagner, not even bothering with him enough to oppose him.

Yet Wagner continues to fascinate. Some of the most imaginative and relevant opera productions today tend to directly address the troubling issues he raised about human nature, society and the environment. In a turn no one could have predicted, an Angeleno Cagean, Yuval Sharon, is about to stage a COVID-appropriate version of “Götterdämmerung” in a Detroit garage. His thinking is very much along the lines of Ginsburg’s: that the notion of a powerful woman willing to undo the system to allow for something new is the message for our times, Wagner willing.

And when isn’t he?

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.