What came after Japanese American internment? A mystery novelist holds the key

- Share via

On the Shelf

"Clark and Division"

By Naomi Hirahara

Soho Crime: 312 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Just as only James Ellroy could have written the Los Angeles Quartet and only Walter Mosley could have crafted Black Angelenos’ experiences into the Easy Rawlins mysteries, crime novelist and research maven Naomi Hirahara was destined to write “Clark and Division.”

For the record:

5:27 p.m. Aug. 3, 2021An earlier version of this article misspelled the last name of Newbery winner Cynthia Kadohata as Kadota.

“So much of my work has been informed by current events and little-known histories,” Hirahara says during a video call one warm summer morning. “While my earlier series involved cold cases where the past was dredged up to solve the current crime, ‘Clark and Division’ is actually my first real historical mystery.”

Out this week, “Clark and Division” spins a capacious crime saga out of a little-known historical episode — the resettlement of Japanese Americans interned during World War II from places like Los Angeles to the heart of Chicago.

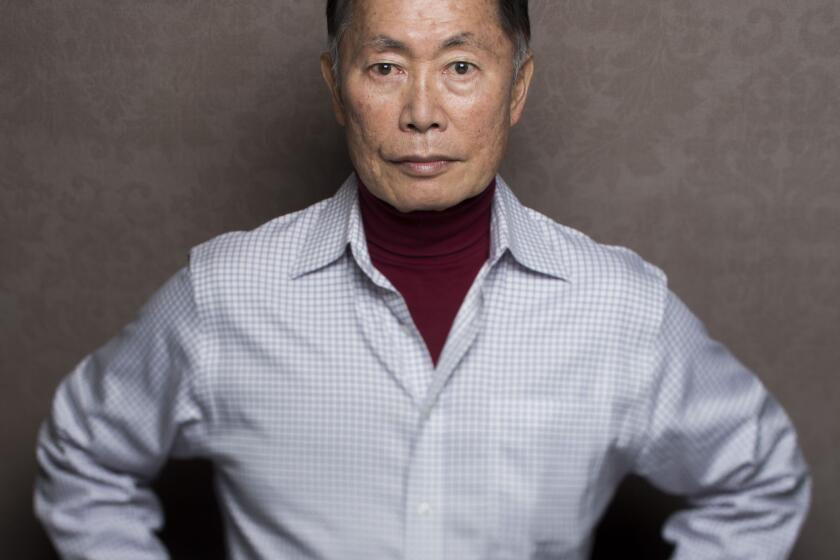

Hirahara, an engaging presence with a sweep of graying dark hair and pink transparent eyeglass frames, spent a decade as a reporter and editor at the Rafu Shimpo, L.A.’s Japanese American daily newspaper, during the battle over redress and reparations for the government’s wartime concentration camps. In those years she also embarked on an award-winning seven-book series featuring Mas Arai, an issei (first-generation) Japanese gardener and Hiroshima survivor whose background is a tribute to her father. She followed up with another series featuring an LAPD bicycle cop.

Hirahara never stopped being a journalist, however, writing or co-writing eight nonfiction books on cultural history ranging from the floral markets of downtown L.A. to the Japanese American community that once thrived on Terminal Island. One of her collaborators was Heather C. Lindquist, an editor and developer of interpretive exhibits for the National Park Service. After working together on an exhibit, in 2018 they co-authored “Life After Manzanar,” a document of incarceration and resettlement that brought Hirahara back to long-simmering ideas.

Her enthusiasm bubbling through the screen, Hirahara asks if I want to see her PowerPoint deck explaining the foundations of “Clark and Division,” which she first developed for a writing workshop at Occidental College. “After I saw this beautiful PowerPoint [Newbery Award winner] Cynthia Kadohata showed during a joint book discussion, I thought it would be fun to look at the images.”

On one slide, her hand-drawn cartoon illustrates the city of Tropico, a once-thriving enclave nearly lost to history. “Maybe 30 years ago,” Hirahara recalls, “I interviewed a Japanese American physician in the San Fernando Valley who told me he grew up in Tropico, which I’d never heard of! Just that one fact, and how I loved the sound of that word, Tropico, stayed in the back of my mind.”

George Takei’s graphic memoir “They Called Us Enemy” depicts his childhood years in an internment camp during World War II.

Hirahara shares the fruits of the research that followed — photos of Japanese farmers from the early 20th century crouching in fields. Nestled between Glendale and what is now Atwater Village, Tropico was where many Japanese Angelenos first settled in the early 20th century. It became the home of the Itos, the family at the center of “Clark and Division”: Pop, who worked as a manager at a Japanese-owned produce distributor; Mom, a homemaker; older daughter Rose, an outspoken beauty; and her little sister, Aki, a Los Angeles City College student who considered herself second fiddle.

It was a solidly middle-class life, and it was severed when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. By March 1942, the family is shipped off to Manzanar War Relocation Center, some 200 miles north of Los Angeles. Rose, perceived as a “model minority” in the camp, is chosen to be among the first of 10,000 Japanese Americans forcibly resettled in Chicago. The Itos later follow.

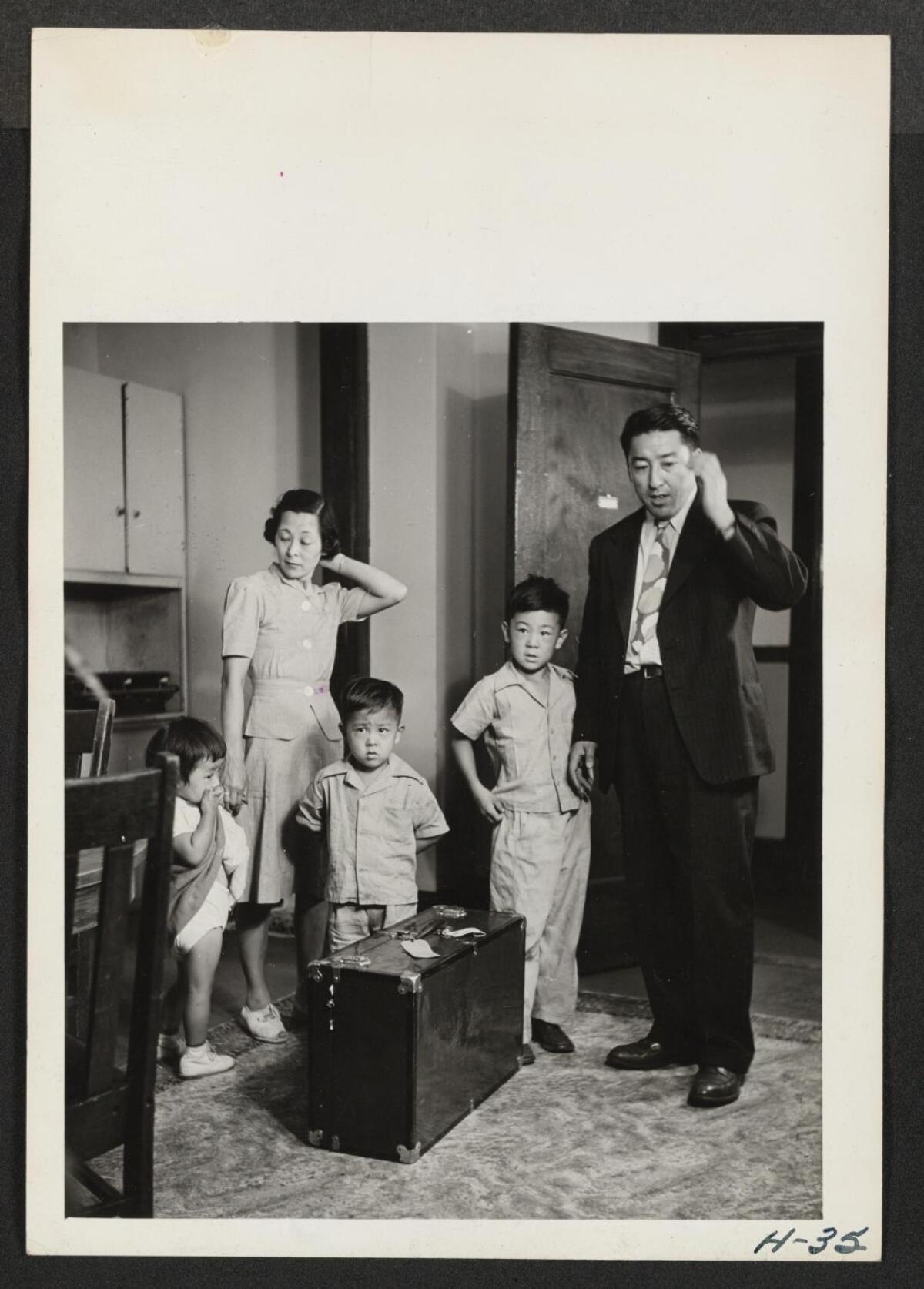

A photo from the Bancroft Library served as inspiration for Hirahara: A resettled family looks with bewilderment at their lone suitcase, dropped unceremoniously in their new Chicago apartment. “In their official photos, the War Relocation Authority liked to present these images that Japanese were happy and smiling, very neat and respectable,” Hirahara says. “In my novel, I try to remove some of that sheen, that mask, not to deny that people participated in the official photos but that it wasn’t the whole story.”

The Itos thought their acclimation to Chicago would be easier because Rose had preceded them and found employment. But it was not so. The family arrives by train, only to learn Rose has been hit by a subway car at the Clark & Division station.

As Aki, now 20, determines to investigate her sister’s death, “Clark and Division” expands into a complex mystery, a coming-of-age romance and an absorbing look into a previously unexplored corner of American history. In its attention to the aftermath of internment, it is light-years ahead of crime novels like James Ellroy’s “Perfidia” or David Guterson’s “Snow Falling on Cedars,” which gloss over Japanese Americans’ experiences in favor of characterizations that flatten their humanity to suit the author’s needs. “Perfidia” in particular hits a nerve with Hirahara.

Masako Miki came to this picturesque landscape of snow-tipped mountains and desert shrubs Saturday on a mission of remembrance.

“I appreciated Ellroy’s rhythm of language and the overall themes,” she says. “But let’s imagine the reality — the thick layer of oppression that prevented Japanese Americans from becoming public school teachers or police officers. How did people adjust, survive or even succeed in such a climate? That’s the more interesting examination, at least from my perspective.”

“Clark and Division” puts Japanese American characters at the center of the story — and the crime. To say more would diminish the joy of immersing oneself in Hirahara’s deeply felt, meticulously researched tale. Everything bears the heft of truth, from the description of Manzanar to the Ting-a-ling Candy Shop, a real store that once stood at the corner of Chicago’s Dearborn and Division streets.

Behind those descriptions, invisible to readers, are archival photos, family albums and ephemera, some of which Hirahara purchased on eBay. To the author, they opened up a world wider than any one story, which she describes as she moves through the slides of young men in zoot suits and pompadours. “All kinds of mostly young people were resettled in Chicago — from the camps, from Father Flanagan’s Boys Town in Nebraska, from orphanages like Manzanar’s Children’s Village. And despite the war, the internment camps and relocation, they wanted to live, to have fun and just be young.”

The vibrant characters, the history and the aura of determined optimism that permeate the novel make it feel like the beginning of a saga not unlike Jacqueline Winspear’s Maisie Dobbs mysteries. Hirahara seems surprised at the comparison; her ambitions are still more tentative. She first thought of “Clark and Division” as a stand-alone mystery. For all her research and travel, she said, “Because I don’t live there, I wondered: Could I adequately describe all the complexity of Chicago in the 1950s? I was much more confident writing about a confined neighborhood.”

Fans can relax: “Clark and Division” is the first of at least two books about the Ito family and their intrepid daughter Aki. “With the Mas Arai series, which went for seven books, I thought I was just writing one book and I said to myself, ‘Wow, this is interesting,’ and I just kept going,” Hirahara says. “So we’ll see what happens.”

Woods is a book critic, editor and author of the Charlotte Justice series of crime novels.

“Widespread Panic,” Ellroy’s latest novel, trades political intrigue for hardcore 1950s gossip via the confessions of real-life lowlife Fred Otash.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.