Why Virginia Woolf matters: What one critic learned from annotating “Mrs. Dalloway”

On the Shelf

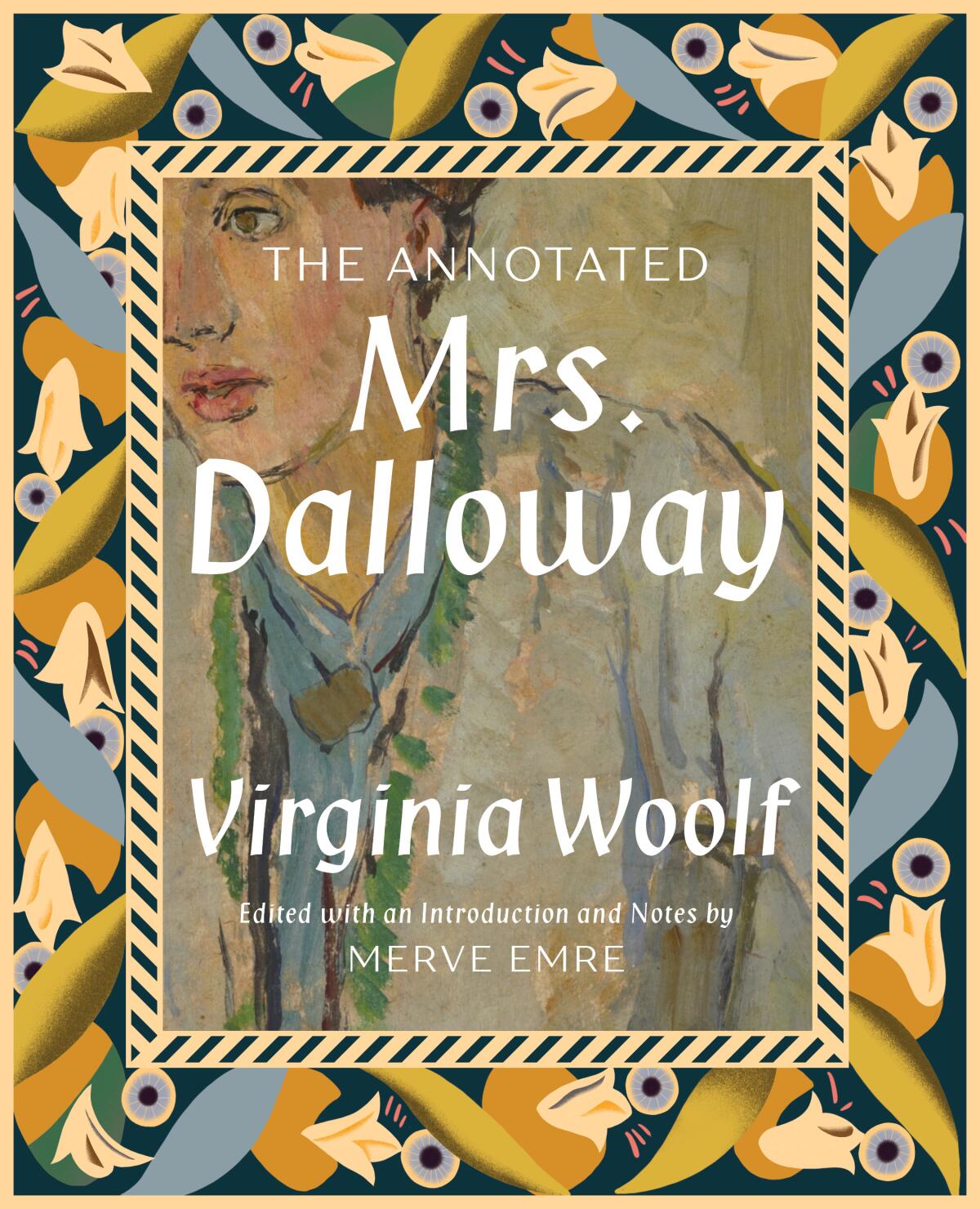

The Annontated Mrs. Dalloway

By Virginia Woolf and Merve Emre

Liveright: 320 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In the introduction to “The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway,” Merve Emre describes Virginia Woolf as the hostess of her 1925 modernist classic: flitting from room to room, introducing us to each of her characters in such a way that their consciousness merges with ours into a collective stream. It’s a fitting metaphor for a book whose title character, Clarissa Dalloway, runs errands for her own party, which will bring the stories of its characters — London’s elite muddling past the traumas of World War I — to a dramatic conclusion.

As the editor and annotator of this new edition, Emre functions much in the same way, leading the reader to a new understanding of “Mrs. Dalloway.” Her hundreds of notes — some quite critical — along with maps, illustrations and photographs, constitute a precious gift for the great novel’s many fans: a careful accounting of Woolf’s process. A critic, professor and previously the author of “The Personality Brokers,” Emre spoke with The Times from her home near Oxford University about Woolf’s conflicted politics, her modern relevance and what we can glean from analyzing her suicide note.

Congratulations on this gorgeous book!

Can I tell you something about the cover? If you go to Woolf’s home, Monk’s House, there’s an amazing mirror that Woolf’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, designed and was then put in this fabric frame, and right across from the mirror is the portrait of Virginia Woolf that you see on the cover. So when you stand in the room, the painting appears reflected in the mirror! When I sent the designers at Norton they saw this and immediately designed this gorgeous cover. This just blew my mind.

Out of all of Virginia Woolf’s books, why “Mrs. Dalloway”?

It hits that sweet spot in her career, the middle period of her novels, and with it a much more deliberate and purposeful understanding of her own craft, which you see in the diaries and drafts. Also, “Mrs. Dalloway” is the first novel I remember reading with another person and writing to them about. That impulse to identify with a character seems to be one of the most pervasive impulses that we have.

Why do readers need an annotated version?

My approach is that the annotator is a kind of companion along with the author, a friendly voice or an occasionally critical or combative voice. I transcribed the entire manuscript myself, and I had never been that close to a text before.

In doing this I realized just how political a novel “Mrs. Dalloway” is! Many of my students ask, “Why should we care about an old posh woman throwing a party?” But when you read it you realize how concerned she is with British imperialism and how bitingly satirical it is. It is about an entire society coming out of lockdown and mass death and how to grieve without compensation.

You’ve lived in America and the U.K. Is there a difference in the way Woolf is read in both places?

I can only give an impressionistic answer, which is in the U.K. she has been canonized in higher education as one of the greatest modernists of her time — and as a great feminist writer, which I feel more ambivalent about. One of the things that has been interesting about writing these annotations is coming to terms with the limitations of her feminism, along lines of class.

I think sometimes people see Woolf as a traditional, upper-crust figure — especially those who haven’t read her work. But this isn’t exactly true.

One of the arguments that is very persuasive to me is that the reason she is able to parody colonialism so well is that she harbors the same prejudices as the characters. I’m not very interested in judging dead writers for the beliefs that they held 100 years ago, but I am interested in how the beliefs are refracted in their novels. What she does in “Mrs. Dalloway”’ is aesthetically interesting enough, and you can hold the beauty of the style and the politics in your mind.

How does that square with her bold queerness?

Woolf’s understanding of sexuality is radical, and it does agitate where she might seem conservative by today’s standards. Sally and Clarissa’s kiss, even at an early age I was trying to figure it out what it was: Is this a lesbian novel or is it not?! Its refusal to settle into those categories is part of its great charm.

Paul Lisicky’s memoir “Later” encapsulates a quarter-century of queer life

Does Woolf’s “stream of consciousness” have any influence on autofiction today?

I don’t think that autofiction is a stable or useful category. Novelists have been drawing from their own lives since Cervantes. It’s just that now we have so many more mechanisms for verification — social media, author interviews — that make autofiction seem distinct from fiction. But I don’t think it is. I was joking with a friend that it should be called “verified realism.”

And what influence did the annotations have on your own work?

It made me a much better reader, to read someone this closely and familiarize myself with all the versions and pieces that go into different editions of one work.

For instance, the first American edition contains a very famous line, which comes immediately after Clarissa learns about Septimus’ suicide: “He made her feel the beauty; made her feel the fun.” Woolf excised it in the British edition but kept it in the American edition. A posh woman derives pleasure from the death of a working-class veteran?! It is an indictment of her character — but is a question for the editors of any new edition, what to do with that line.

I’ve always thought of that line in the sense that someone else’s suicide forces us to reevaluate our own choices.

Woolf revised the scene of Septimus’ suicide extensively: “Life was good. The sun hot.” In one draft, she adds that line, “the sun hot.” One way you can read this is that he kills himself so that he isn’t confined or institutionalized — he’s choosing life by killing himself.

When you read the drafts of Woolf’s suicide note, you see these same ideas reflected. In the second draft, all the “I’s,” “I can’t read,” etc. are removed, so the note ends up being entirely about [her husband] Leonard. It’s very unsettling in part because she’s enacting self-annihilation even through the act of writing.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.