Toni Morrison called her only short story ‘an experiment.’ But it’s no game

On the Shelf

Recitatif

By Toni Morrison

Knopf: 96 pages, $16

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

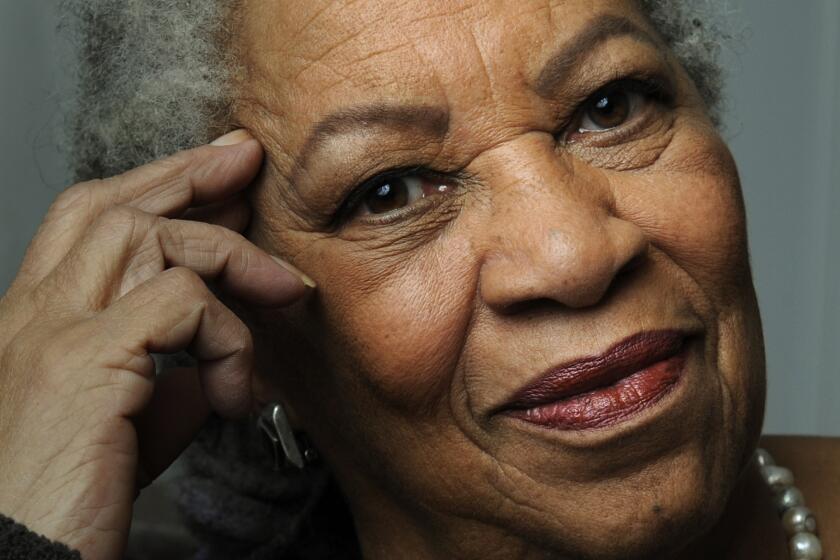

I’m at a bit of a loss over how to write about Toni Morrison’s “Recitatif.” The only short story ever written by the late Nobel laureate, who would have turned 91 this week, “Recitatif” was originally published in 1983 in “Confirmation: An Anthology of African American Women,” a collection edited by Amiri and Amina Baraka. Now it’s been issued as a book of its own, with a typically insightful introduction by Zadie Smith.

“The fact that there is only one Morrison short story,” Smith writes, “seems of a piece with her oeuvre. There are no dashed-off Morrison pieces or ‘occasional essays,’ no filler novels, no treading water, no exit off the main road. There are eleven novels and one short story, all of which she wrote with specific aims and intentions.”

Morrison never writes without purpose. “Toni Morrison does not play,” Smith observes. “When she called ‘Recitatif’ an ‘experiment’ she meant it. The subject of the experiment is the reader.” The story is an extended attempt to write about race by, in the most fundamental sense, writing around race as a strategy not so much for making us complicit — Morrison understands that we are already complicit — as for provoking us to confront that complicity.

As for how she manages this, if you’ve read “Recitatif” — it has been discussed and taught since its initial appearance — you understand already. If not, discovery is a key reason we come to narrative. The turn here, the twist if you will, comes in how Morrison addresses (or doesn’t) the racial identities of her characters, the way she uses the story to show us our preconceptions, offering details that are by turns sharp and ambiguous. What she’s doing is not to implicate us so much as to lead us to implicate ourselves.

To experience “Recitatif” for the first time is to remember that books, at their best, teach us how to read them. The story is so simple yet at the same time so ingenious. We wonder: Is she really doing what I think she is? Then you realize: Yes, she is. In the spirit of that fresh approach, I won’t be more specific about the experiment. In fact, I might suggest you read Morrison’s story first and Smith’s introduction afterward. The pieces are very much in conversation with each other. Equally important, both seek to be in conversation with us.

Toni Morrison, the author, essayist and winner of Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, famously encouraged would-be writers to take action.

Do I need to say that this is a form of generosity? But, of course, that’s what literature — what Morrison — offers: an angle of engagement with the world. Consider how she frames “Recitatif,” as if we were already in the middle of things. “My mother danced all night and Roberta’s was sick,” the story opens. “That’s why we were taken to St. Bonny’s.”

The narrator is an 8-year-old named Twyla, although she is also, we will learn, the adult looking back. She and Roberta meet as roommates at a New York orphans shelter. One is Black and one is white, “like salt and pepper standing there.” Even as they form a society of two, Twyla recognizes that theirs is a relationship of convenience. “We didn’t like each other all that much at first,” she confides, “but nobody else wanted to play with us because we weren’t real orphans with beautiful dead parents in the sky. We were dumped.”

What strikes you first is the language, the way Morrison makes it do so much. That riff about the beautiful dead, which repeats more than once, clearly represents the 8-year-old’s perspective. Yet underneath its surface we intuit the older Twyla peeking through. Parents in the sky — it’s the kind of euphemistic deflection offered by adults such as “the Big Bozo,” as the orphans call their overseer. Twyla, though, is too smart for that. When her neglectful mother comes to visit, she is flush with glee.

“I was feeling proud,” she tells us, “because she looked so beautiful even in those ugly green slacks that made her behind stick out. A pretty mother on earth is better than a beautiful dead one in the sky even if she did leave you all alone to go dancing.”

A similar double vision recurs throughout “Recitatif,” which moves from St. Bonny’s to a highway Howard Johnson’s, where Twyla and Roberta reencounter each other, and later to the Hudson Valley community of Newburgh, where both settle as adults. The location is hardly coincidental: “Geography, in America, is fundamental to racial codes,” Smith asserts. “[A]nd by the time Morrison wrote ‘Recitatif,’ Newburgh was a depressed town, hit by ‘white flight,’ riven with poverty and the violence that attends poverty.”

The novelist and essayist’s slim new collection, “Intimations,” probes our COVID-19 reality as well as her own gifts, blind spots and vulnerabilities.

It’s a perfect place, in other words, for the pair of reckonings that bring the story to fruition: the first about busing (Twyla and Roberta are on opposing sides of the issue) and the second involving an incident from St. Bonny’s, in which a mute woman named Maggie — “She was old and sandy colored and she worked in the kitchen” — fell while walking to the bus. “We should have helped her up,” Twyla admits, but instead she and Roberta mocked her. “And it shames me even now,” Twyla continues, “to think there was somebody in there after all who heard us call her those names and couldn’t tell on us.”

It is with Maggie that Morrison’s purpose reveals itself. That first description of the incident is a throwaway; it is forgotten, or set aside, as soon as it is over. And yet, as Faulkner wrote, the past is never past, which means the incident must fester for Twyla and Roberta both. Was Maggie Black or white? The two have different recollections. Their memories shift each time they come up. Did she fall or was she pushed? Did Twyla and Roberta participate in the aggression? Does it matter if they meant to cause her pain? “[W]anting to is doing it,” Roberta says during their final encounter. Even as the story ends, the truth remains beyond their reach.

It would be enough if this was where Morrison had chosen to leave us, in the slipstream of her characters’ subjectivity. It is so if you think so, to borrow a phrase from Luigi Pirandello: the notion that narrative, or identity, must be conditional, a reflection of the observer more than the observed. Morrison, however, doesn’t stop there; throughout “Recitatif,” she turns that conditionality back on us.

“A black girl and a white girl meeting in a Howard Johnson’s on the road and having nothing to say,” Twyla remembers. “Two little girls who knew what nobody else in the world knew — how not to ask questions. How to believe what had to be believed.” She and Roberta are all this and more. What’s essential, though, is that the way the characters flow in and out of one another requires us to confront something about ourselves. What are your preconceptions? Morrison demands. What do you take for granted in the world? And what if you are wrong? Not about everything, necessarily, but about the most important thing?

What does it mean not to know?

With “Beloved” and other writings, Toni Morrison gave voice to the silences in the past and created some of the most memorable characters in American literature.

Ulin is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.