The glamour and the underbelly of the hippest party house in 1960s L.A.

- Share via

On the Shelf

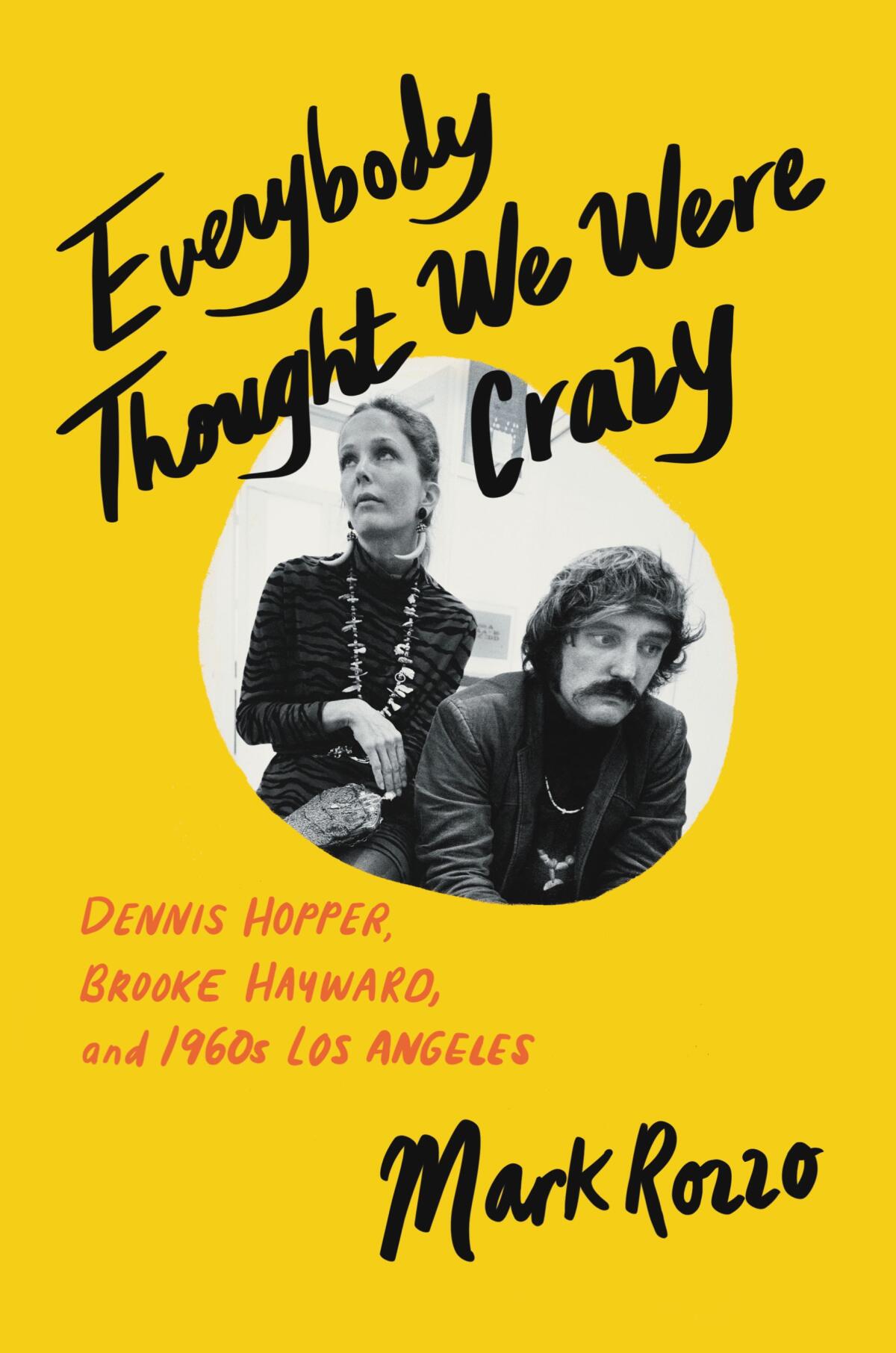

Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward, and 1960s Los Angeles

By Mark Rozzo

Ecco: 464 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

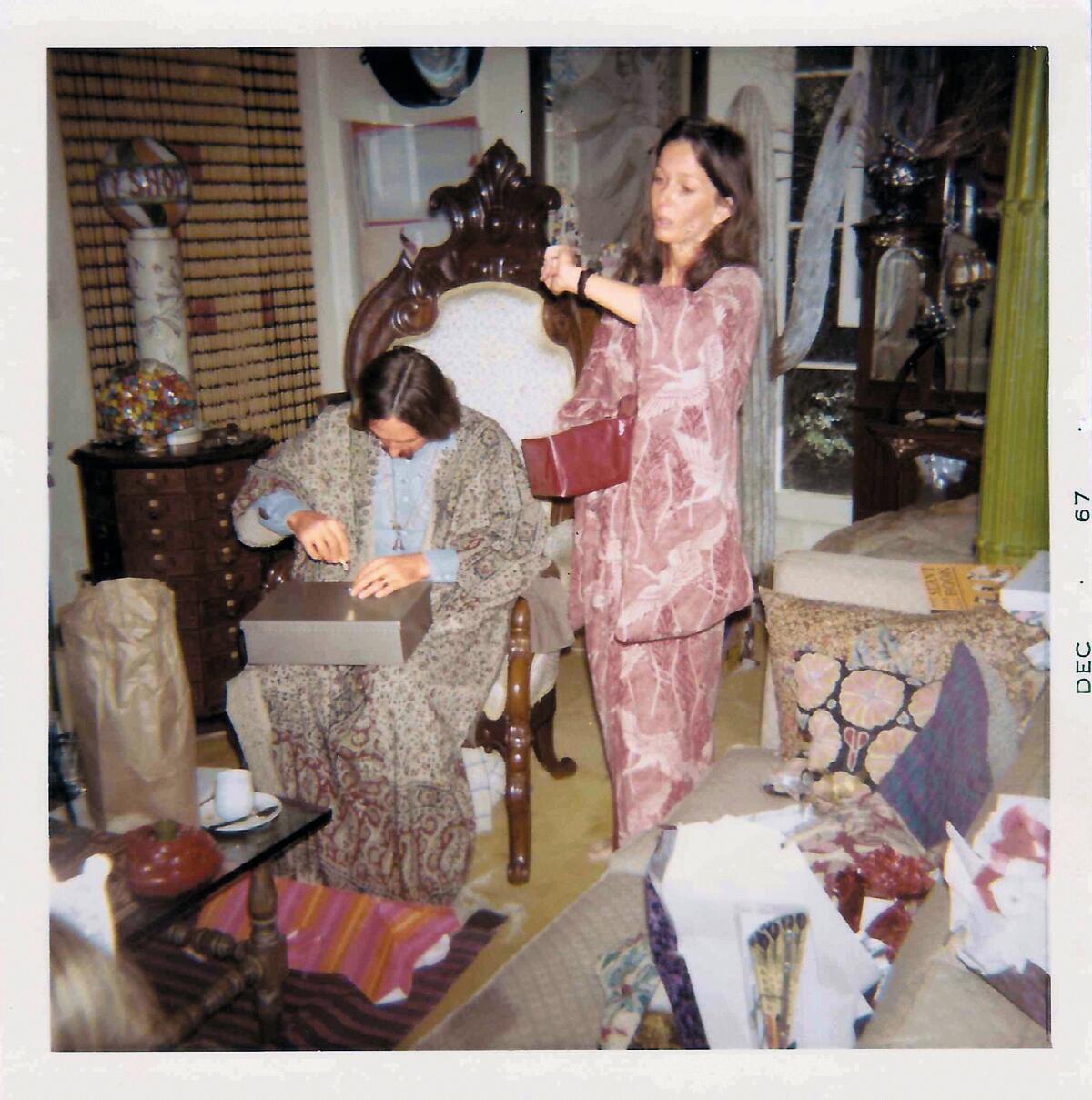

BROOKLYN, N.Y. — Before the ‘60s were what we know as the ‘60s, the house in the 1700 block of North Crescent Heights Boulevard hosted an ever-evolving mix of art and artists, working and nonworking actors, the adult children and slightly feral grandchildren of Hollywood’s golden age, musicians not yet famous, writers, gallerists, directors and random people in cool outfits who’d been invited up from Sunset Boulevard. For most of the decade, Brooke Hayward and her husband, Dennis Hopper, threw what might just have been the best parties in L.A.

If you’d been there in 1964, would you have realized that the guy with the grass was Peter Fonda, the one by the stereo was David Crosby, the silk-screen print in the kitchen of two Mona Lisas was by Andy Warhol? Sometimes it takes a few decades for the magic to come into focus. Mark Rozzo brings the lost scene to life in “Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward and 1960s Los Angeles.”

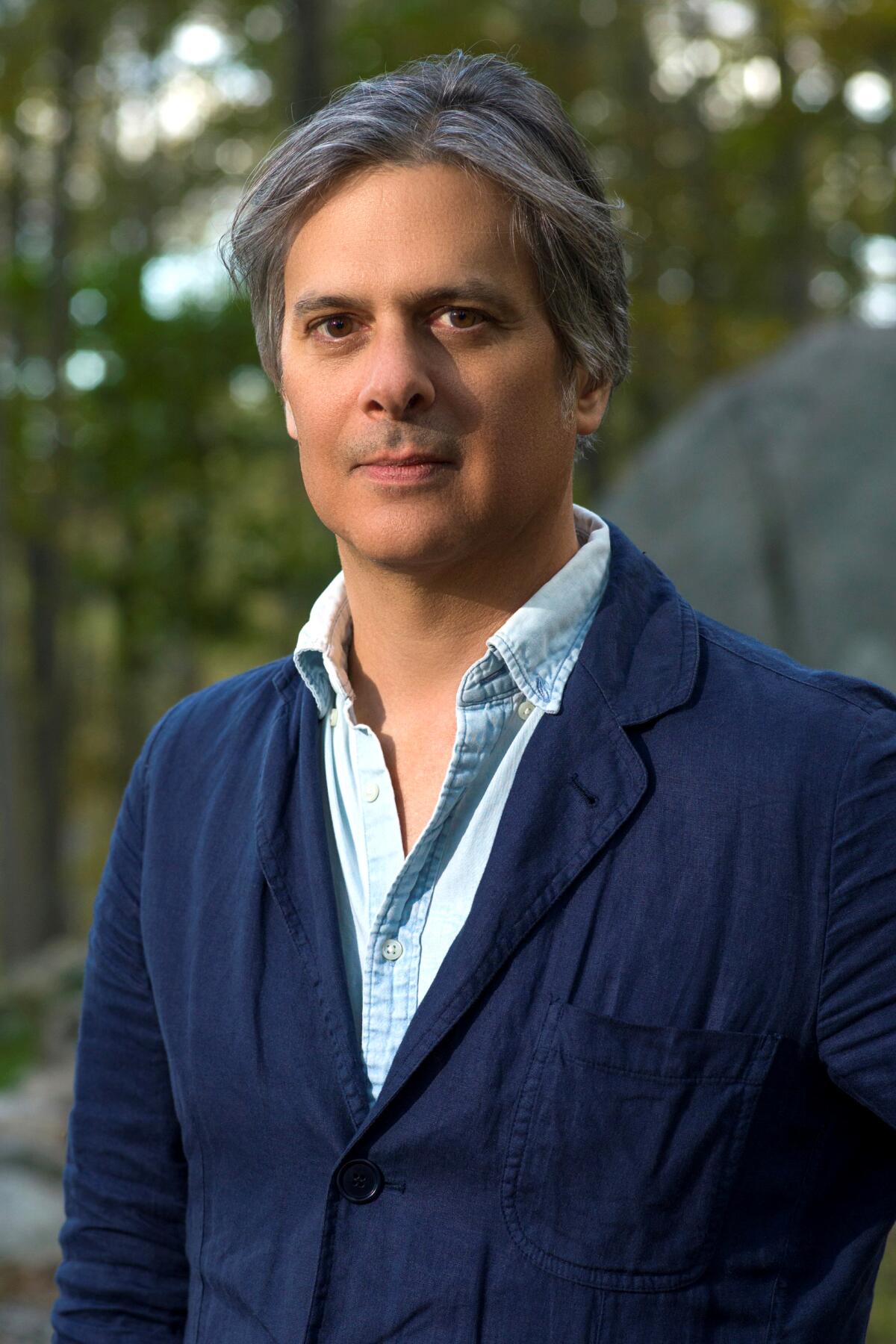

“The fact that there seemed to be concurrent revolutions in the world of art, the world of music and the world of film really made it so dynamic and interesting,” Rozzo told me. “I think that there was something singular in the way that Dennis and Brooke connected all those worlds.”

We were sitting on a shady patio in Brooklyn, 2,806 miles from the house Hopper and Hayward owned in Hollywood more than 50 years ago. “L.A. in the ‘60s was so fascinating to me; we’re talking about a place that has been compared to Paris in the ‘20s. Whether or not the comparison is completely irresponsible, I’m not here to debate that.” Point is, he was besotted.

Dennis Hopper’s carnival ride through life

The book focuses on Hopper and Hayward’s marriage, which lasted from 1961-69, and the worlds they moved through. Hayward was the daughter of actress Margaret Sullavan and agent Leland Hayward, so they regularly got looped into the orbit of Hollywood power brokers such as David O. Selznick and Jennifer Jones. Hopper was one of the Hollywood crew invited to join civil rights marches in the South; he photographed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma. Hayward had been on the cover of Vogue and Life, but she was distinctly bohemian, filling their house with unfashionable oddities and buying Pop art from friends showing at Ferus Gallery — a crew now famous, but then not at all.

The book follows Hopper and Hayward separately until they meet on the ill-fated play “Mandingo,” then slows down for the early, happiest days of their marriage before, like the ‘60s, it spirals downward. Reading the book can feel at times like an obstacle course over dropped names. But when given time to stretch, “Everybody Thought We Were Crazy” does a good job of giving people enough time to explain themselves, or work fruitlessly on projects, or show up making misunderstood art.

To be enticing to us in 2022, a story like this has to walk a tightrope, featuring figures famous enough to grab our attention while also telling us something new. I wish Hayward had top billing in the subtitle — she’s still with us, seems uniquely creative and spirited, and once wrote a bestselling book (“Haywire,” 1977) about her privileged but troubled upbringing. With the encouragement of daughter Marin Hopper, Hayward learned to trust Rozzo, sometimes sharing stories over BLTs at a tavern in Connecticut. But Hopper is the bigger star, the name you’re most likely to recognize.

How you think about Hopper depends on where you came in. For some, that would be his masterful, demented turn as Frank Booth in David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet” or his unhinged performance in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” For others, it was the clean, redeemed Hopper — “Hoosiers,” “Speed” — living in a Frank Gehry-designed compound in Venice. For fans of classic film, he’s the intense co-star of James Dean in both “Rebel Without a Cause” and “Giant.” But if you know Hopper for just one thing, it’s probably as the co-writer/director/star of 1969’s “Easy Rider,” the independent film that blew up Hollywood and changed American filmmaking.

That story has been told much before, in books such as Peter Biskind’s “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” and “Pictures at a Revolution” by Mark Harris. “I couldn’t write that book now,” Harris told me. “Because just in the 18 years or so since I started researching it, so many of the people who were doing interesting things and were part of the fabric of the Hollywood scene back then have died.”

Dennis Hopper dies at 74; actor directed counterculture classic ‘Easy Rider’

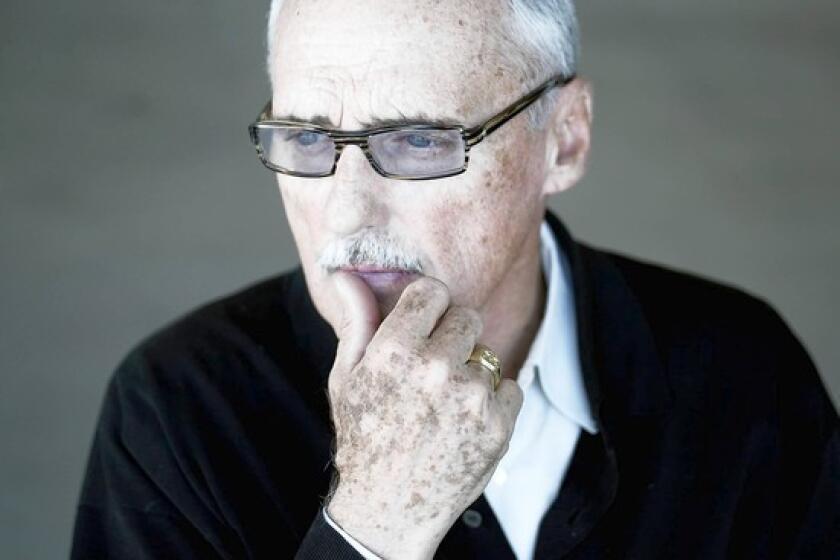

Hopper died in 2010. “I’ll never have a chance to talk to him,” Rozzo said, but one key figure among the many he did talk to was Hopper’s younger brother David. “When I was sitting with David, those blue eyes, the presence, I was like, this is the closest I’ll ever get.”

Rozzo also dug into archives, of course. He found that essayist and oral historian Jean Stein not only interviewed Hopper extensively, she also talked to his mother. He got to read correspondence by a Scottish nanny who wrote home about the comings and goings at the North Crescent Heights residence, the extraordinary side-by-side with the everyday. He had access to some of Hayward’s private writings and her father’s archives. And he got to see Hopper’s proof sheets.

“Dennis created 18,000 images with his camera in the 1960s,” Rozzo said. Hayward gave Hopper a camera when they first got together, and he carried it everywhere. I had thought of Hopper as something of a photography dilettante, but Rozzo makes the case that his work had genuine artistic merit.

Yet the contact sheets held another sort of value for a cultural historian: chronology. “I would just pore over them,” Rozzo said. “My challenge was to take a largely visual record from Dennis and turn it into some kind of written narrative.”

Rozzo is an East Coaster, but longtime readers of The Times book section will recognize his byline — he was a regular contributor in the mid-2000s. During that time, he once spent a month living in L.A. “I was living the dream, up in a canyon with my Frye boots, my denim shirt, my 12-string guitar. I loved it … the entire time I was there I felt like I was becoming an armchair student of L.A. cultural history, wanting to do something, not sure what it should be.”

Mark Harris’ masterful biography of Nichols, director of ‘The Graduate’ and much more, explores an artist who succeeded by having no fixed identity.

He fell in love with an L.A. era that appeals to many cultural historians. “It’s a period that ceaselessly fascinates me,” said Harris, most recently the author of the biography “Mike Nichols.” “You’re looking at a really interesting, fertile, churning set of artistic movements and revolutions in the making, not just one.”

Two significant factors distinguish that time from ours. First was its relative isolation. What was happening at the intersection of music and art and film in New York, London or even San Francisco was substantially different from what was happening in Los Angeles. The internet and Instagram may unite us today, but now everybody can see everybody else’s new boho chic.

The other, sadly, is money. Rozzo writes that in 1965, Hayward’s lifelong friend Jane Fonda and her French director boyfriend Roger Vadim rented a beach house in Malibu for $200 per month. Adjusted for inflation, that would be about $1,800 today. That same 1930 house, since renovated, is currently available for rent — for $125,000 per month. You have to have much, much more money in the 21st century to live like a bohemian.

But even if it was easier to take creative risks in those days, there was something special about Hopper and Hayward. Before he made “Easy Rider,” Hopper was oh, so close to getting another picture made (“The Last Movie,” which was eventually a disaster). He’d gotten some money but kept falling short. He and Hayward were invited to the home of a wealthy friend to meet Doris Duke, then considered the richest woman in America.

All Hopper had to do was charm her and he could get the money for his film. He was outrageously late, rolling in from the Human Be-In in San Francisco without stopping to bathe or change. And when tasked with giving Duke a ride home, Hopper skipped his film pitch and lectured her on socialism.

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

“I love that little moment,” Rozzo said, “Because Brooke is not very pleased with Dennis blowing off the dinner, coming in late looking the way he did. Their relationship is starting to get into a very weird place at that part. They’re clearly on diverging paths.” And yet, as he writes, “Brooke said she had never loved anything as much as watching Doris Duke run for safety that night.” As bad as things would get — and they would get very bad — Hopper and Hayward were on the same page.

Kellogg is a former books editor of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.