Review: Anthony Marra’s new novel both celebrates and punctures American myths

On the Shelf

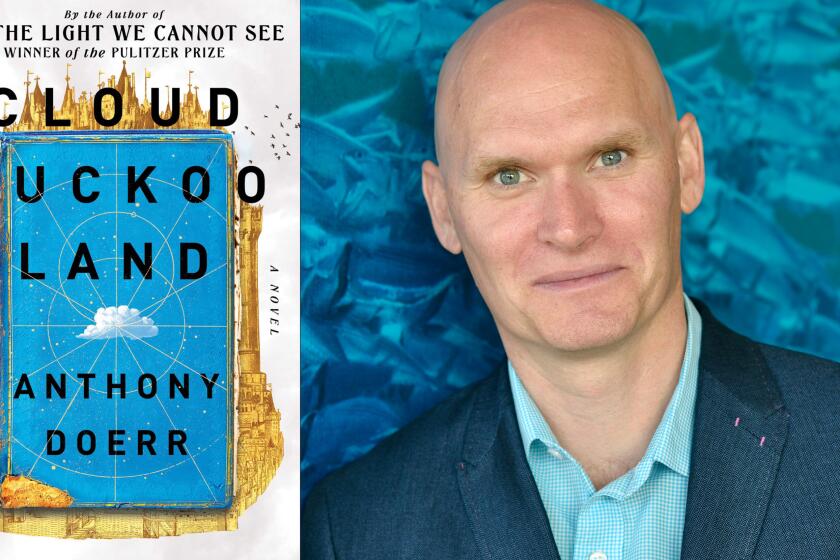

Mercury Pictures Presents

By Anthony Marra

Hogart: 432 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

As our country spirals into more and more discord over who did what on Jan. 6, 2021, and whether women should have reproductive rights, it seems right and proper for a novel concerning World War II-era Italian fascism to highlight how easy it is for all of us to fall prey to false romantic narratives. All the better if the author is Anthony Marra, and the book “Mercury Pictures Presents” does so through the perspective of a poorly run Hollywood film studio.

The book sounds almost like Fellini in reverse: Life itself provides the ridiculous parts. Only make-believe can save us. Though as protagonist Maria Lagana discovers, sometimes make-believe is just as dangerous as reality. An Italian immigrant who has made a dark personal choice that lands her in a Los Angeles house with her mother and various maiden aunts, Maria has managed to become associate producer and deputy to Artie Feldman, the co-owner, with his brother Ned, of the titular ramshackle studio.

Marra, whose 2013 novel, “A Constellation of Vital Phenomena,” told the story of Chechnyan war refugees and whose 2015 story collection, “The Tsar of Love and Techno,” was set in the mid-20th century USSR, possesses a seemingly inexhaustible imagination. He can conjure both a bleak Italian hut and a gossipy American household, both a farcically bickering pair of siblings and the interior world of a Chinese American actor.

He also knows exactly where to insert historical anecdotes and when to opt for pure invention, weaving it all together with witty asides. Maria thinks “her great-aunts’ understanding of Catholicism was so fickle you couldn’t really call it monotheism. It was a protection racket.” To them, “Like any invasive procedure, it was best to get matrimony over with while you were young enough to bounce back.”

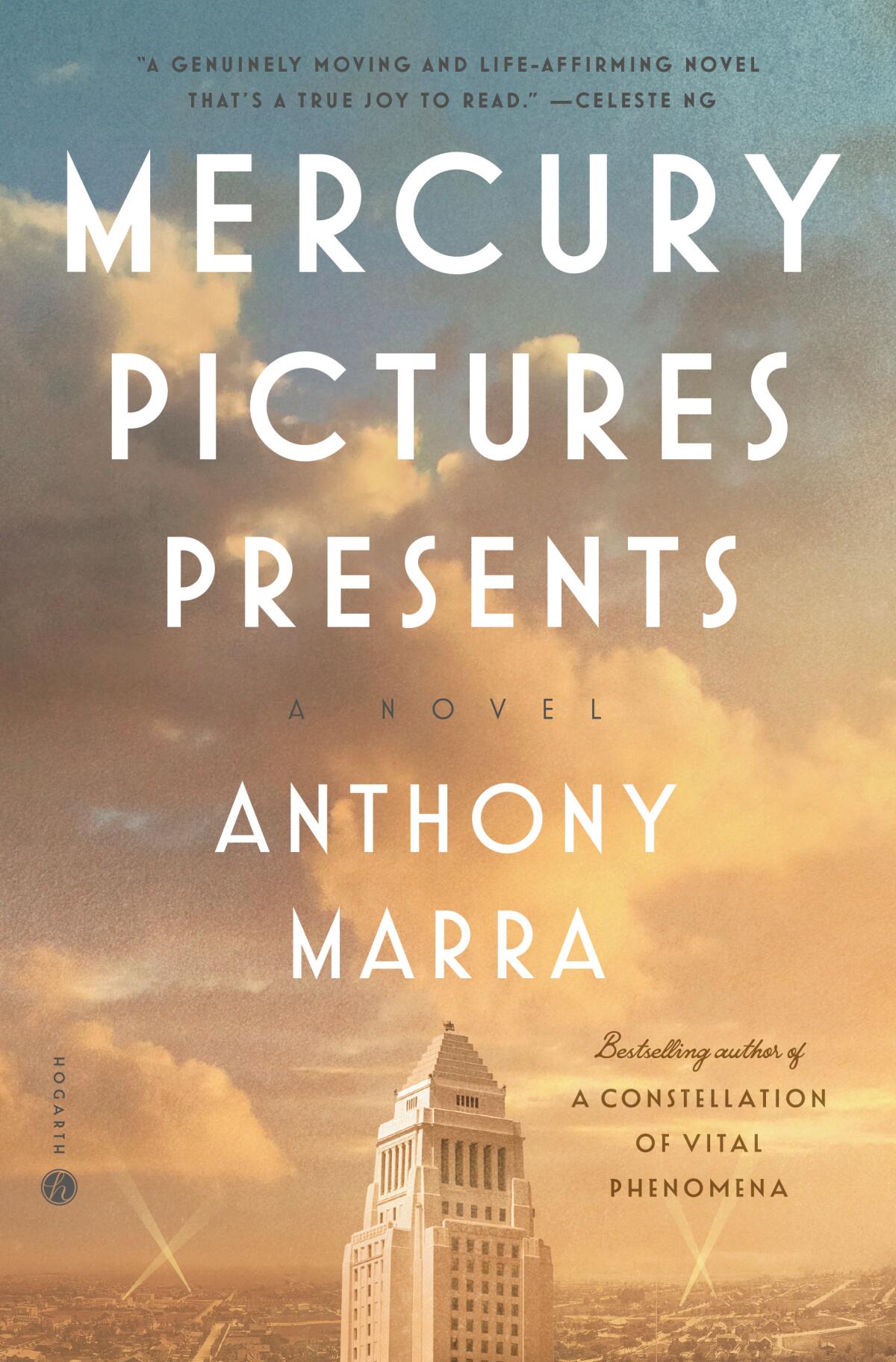

‘Cloud Cuckoo Land,’ Doerr’s followup to ‘All the Light We Cannot See,’ ambitiously maps a world connected by stories — if we know how to read them.

The first third of “Mercury” feels aptly cinematic, whirling readers through half a dozen scenes so varied that they feel like a passel of movie trailers, more evocative than narrative. The action ping-pongs from Maria and Artie’s “Adam’s Rib”-like repartee (fully platonic, as Maria remains steadfast to her true love, Eddie Lu) back to her father Giuseppe’s confinement by Mussolini’s thugs and on to Artie and Ned’s Borscht-Belty Punch and Judy show.

If these set pieces were the trailers, what’s the feature film? Strangely, there doesn’t seem to be one in “Mercury Pictures Presents.” After a long section in Italy that involves a stolen identity, a village boy turned Mafia kingpin and a harrowing escape, we get two more long shaggy-dog stories: Eddie Lu acting in American propaganda films; German emigrée Anna Weber watching her architecturally precise miniatures of Berlin used in bombing test-runs. Woven throughout is the story of Vincent Cortese, a photographer whose camera is taken away due to his status as an “enemy alien.”

Maria is another “enemy alien.” One of Marra’s themes in this novel is confinement of all kinds. Giuseppe and his comrades, restricted to an invisibly demarcated “confino,” comply because they have nowhere else to go, while Maria seeks out a tiny, hidden office space on a studio lot to pursue a passion project in private. Anna mentally confines herself to the Kreuzberg streets of beloved memory. And as for Eddie, a would-be leading man, his Asian features relegate him to voiceovers and bit parts, confinements reflecting another ugly facet of wartime xenophobia.

“Mercury” begins and ends in Italy, which makes sense within the logic of the plot, but its deepest meaning, if not its main action, lies in Eddie’s realization about how a government simultaneously uses and abuses citizens. His epiphany involves the treatment of Asian Americans, but given the various groups whose talents are swept up and spit out by the war machine (painters, writers, scientists and more), the threat has tentacles that, Marra might agree, could reach all of us if left unchecked.

The author of ‘A Gentleman in Moscow,’ a consummate historical novelist, comes home with a 1950s story of boys riding forth into a chaotic future.

At one point, Artie wonders “how to act morally when moral action incites egregious immorality in response.” Could there be a more succinct way to talk about modern warfare? After Maria meets Leni Riefenstahl and views the famed director’s work in service of the Third Reich, she is troubled by “the spectacle of a filmmaker pressing her undeniably singular vision into the service of a picture that denied the singularity of individual experience.”

Maria decides “Riefenstahl couldn’t be outdone ... only undone” and starts to plan “The False Front,” a pastiche of a production combining studio B-roll of war scenes with bare-bones new material. Her project echoes the revelations of the poor, dispossessed photographer Vincent and brings to mind Susan Sontag’s essays on the form.

In other words, Maria aims to show that it’s not what a photographer shoots, but how: “It was the unsteady presence of the photographer’s mortality ... that created a sense of authenticity. It was realism perfected by error. The constant reminder that you were watching a faulty record made it viscerally trustworthy. And this, of course, was manipulable.”

For Eddie, participating in the manufacture of that facade ultimately proves untenable in light of Hollywood’s prejudices — not to mention the nation’s internment of Japanese Americans. Marra, however, knows he is the director of his own novel; he won’t give in to disappointment and despair. Instead, he brings readers back across the Atlantic Ocean to Italy, where a great wrong is made right not through confession or the wheels of justice, but through unstinting love and forgiveness.

Bethanne Patrick’s August highlights include fiction from Mohsin Hamid and Marianne Wiggins, a sequel to “Dopesick” and a revisionist feminist history.

Is this too pat a conclusion, an affirmation of the American passion for happy endings as manipulative as the faux authenticity that sets Eddie on edge? Marra has, though, been smart enough to sprinkle his novel with unhappier endings, so that when this one good thing happens it feels earned, even … authentic.

Although “Mercury Pictures Presents” is uneven and downright discursive in many places, its cinematic scope ultimately achieves a grandeur beyond its particulars. Besides, we could all use a grand narrative now and then, especially now, when such a thing seems to recede past the horizon with every passing day.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.