Review: How a Guatemalan kidnapping inspired Eduardo Halfon’s autofictional ‘Cancion’

- Share via

On the Shelf

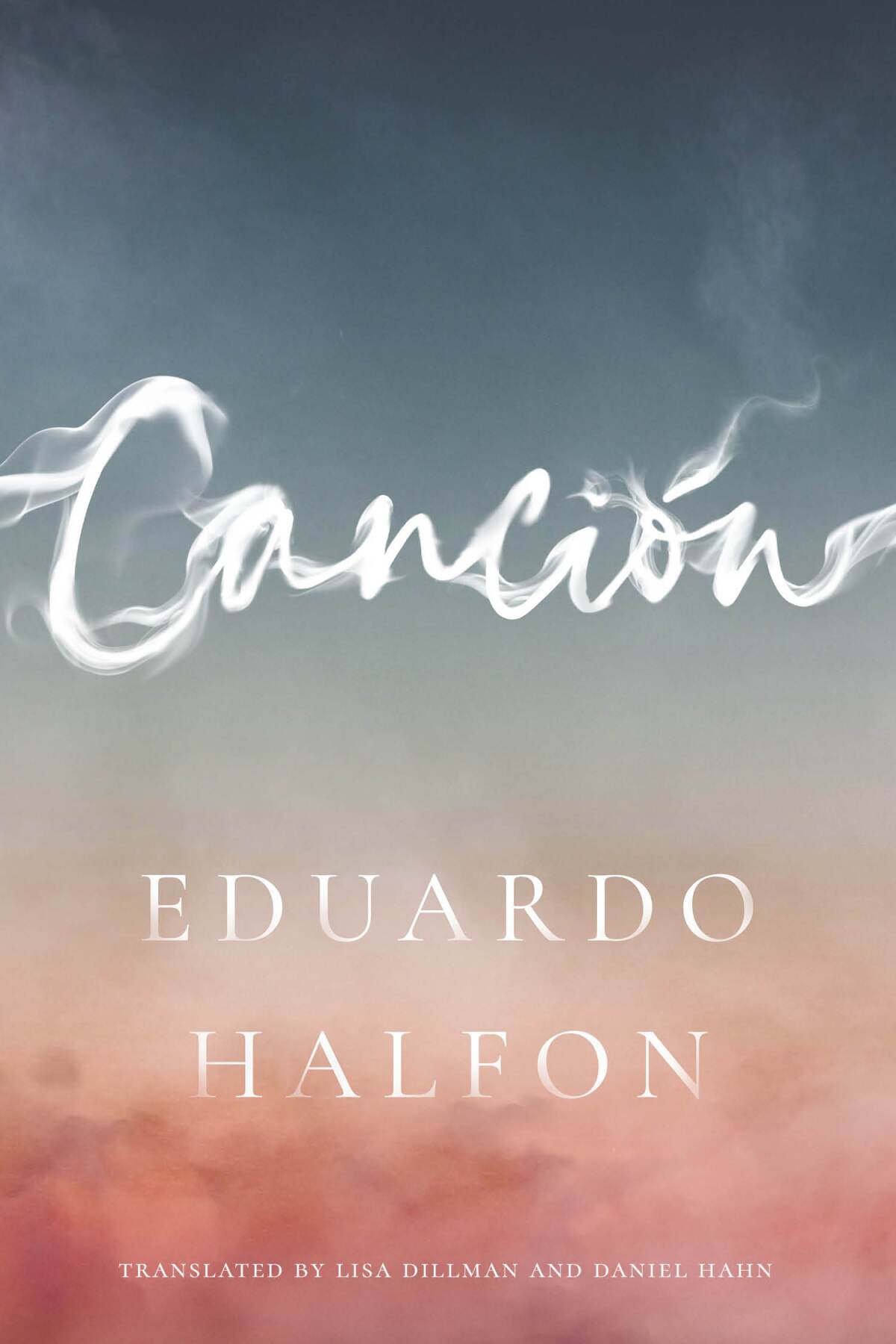

Canción

By Eduardo Halfon

Bellevue: 160 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

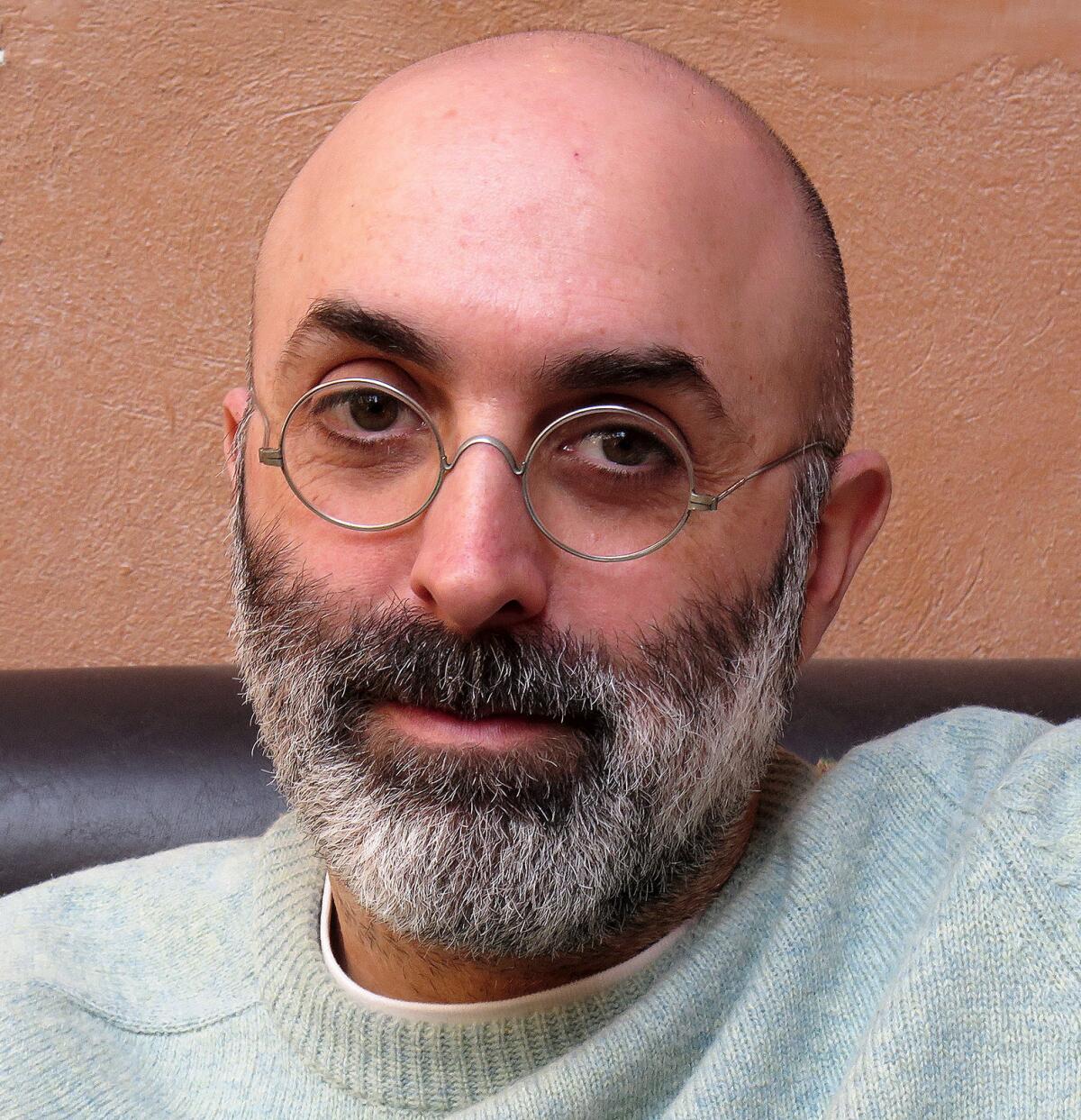

“Every writer of fiction is an imposter,” Eduardo Halfon insists near the end of his new book, “Canción.” The declaration is both an admission and a challenge. Halfon — or his narrator — has come to Tokyo for a conference on Lebanese literature. The connection is tenuous at best. Yes, his paternal grandfather left Beirut in 1917, but that was three years before Lebanon was founded. It was still “part of Syrian territory.” As for what this means for Halfon’s family, it should be simple. “Legally,” he acknowledges, “they were Syrians.” But simple is not always so simple: “They called themselves Lebanese. Perhaps as their race or their people, the way it was written in the logbook. Perhaps as their identity. And so I am the grandson of a Lebanese man who was not Lebanese.”

Like so much of Halfon’s writing, the narrative of “Canción” unfolds in an elusive middle ground where heritage becomes porous. For anyone familiar with his project, this will not come as a surprise. The author is a diasporic figure: Born in Guatemala City, raised there and in Florida and educated in North Carolina, he has lived in Europe and Nebraska. His métier is family: the way we are shaped by it and the way we push back on or move beyond it; how it both supports and limits us. In “The Polish Boxer” (2012), his first book to be translated into English, this leads him to consider his other grandfather, who survived Auschwitz with the help of a fighter who came from his village. “Mourning,” his most recent book, revolves in part around his uncle Salomán, whose drowning as a child resonates in “Canción” as well.

What Halfon finds particularly compelling is memory and how it may or may not accrue. In that sense, he is working the territory of autofiction, not so much creating narrative as using it to frame a set of inquiries. He does not seek a definitive story because he understands no story can be definitive; each is influenced by who we are and what we wish to know. With “Canción,” that means excavating the saga of his grandfather’s kidnapping, four years before the author’s birth, by Guatemalan rebels who held him for ransom for 35 days.

L.A.’s authors, from 19th century novelists to Wanda Coleman to Steph Cha, have always pushed genre boundaries and dissected California myths.

How to build a book around a bit of history you didn’t witness, one shrouded in mystery and even myth? Here we see the fictional aspect of the autofiction — “Canción” comes labeled as a novel — although for Halfon, such signifiers remain beside the point. Instead, he is interested in the incremental passage from one moment to the next. He structures his book as a series of nested digressions, jumping from Japan first to his grandparents’ lavish home in Guatemala City, where, in the late 1970s, during a dinner with cousins from Argentina, the family is interrupted by a detail of soldiers, “serious, mustachioed, in their tight khaki uniforms,” requesting an audience with “the man of the house.”

Halfon’s first-person character is too young to know what’s happened; all he can describe is what he sees. This includes the soldiers, as well as the image of another Salomán, not a blood relation but a family fixture nonetheless, who reads the fortune of a guest in the grounds left in her coffee cup. Salomán does not reveal what he sees, an act of narrative reticence that will be echoed as the book progresses. Remembering this moment, the narrator reminds us that we are compelled to find meaning in incompletion, even as he complicates our sense of time and space:

“Some of the family thought he’d seen Nono’s impending death. Others, that he’d seen Berenice and her parents’ hasty return to Buenos Aires. Others, that he’d seen the reflection of the present, of that moment, of all those soldiers prowling through the house like wild beasts while one of them — I would learn decades later — was in the study, informing my grandfather of the final whereabouts of one of the men who had kidnapped him in January of 1967.”

The effect of these lines, which reach back into the past while projecting far into the future, is that of a rebus, with the stunning phrase “the final whereabouts” offering one more breath of indirection. Surely he means the kidnapper’s resting place? Halfon, however, is less concerned with how he died than who he was. “They called him Canción,” he writes, introducing both the man and the long central chapter of the book, “because he used to be a butcher. … Or at least that’s what some of his friends claimed.” That final proviso recalls to us the shaky ground we’re on.

Knut Hamsun’s novel ‘Hunger’ is found on a bench in the south of France and completely disintegrates as it is read one last time.

Halfon heightens the tension by cutting back and forth from the kidnapping itself to an account of the narrator waiting, decades later, in a Guatemala City bar for a source who will soon tell him: “I’m asking you to never, under any circumstances, write anything about what we discuss. Alright?”

I’m not going to reveal what Halfon does with the information, whether he discloses it or not. But it’s suggestive that he should name his book after the kidnapper — who is, by turns, consequential and something of an extra, both a catalyst and a mechanism of the plot. Without him, nothing happens: not only the kidnapping but also the dinner years later and even, one imagines, the framing trip to Tokyo. At the same time, Halfon keeps asking, what is plot or narrative? Are its consolations in the resolution, or the questions it provokes?

The answer is both and neither. Or perhaps it’s that all books operate according to their own rules. “I imagine Canción suddenly turning into a singer in the Suchiate River,” Halfon writes, “and singing his killer a song that is both sad and sweet about a Lebanese Jew who long ago gave a guerrilla fighter a couple of dazzling gold pens, one final song before the crack of one final bullet exploding in the dark tropical night.” We are who we imagine we are, in other words, which is the faith that sits at the heart of family and literature.

Every writer of fiction is an imposter, indeed.

The latest from Ling Ma, Yiyun Li, Russell Banks and Namwali Serpell as well as exciting newcomers round out our critics’ most anticipated fall books.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.