Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Review

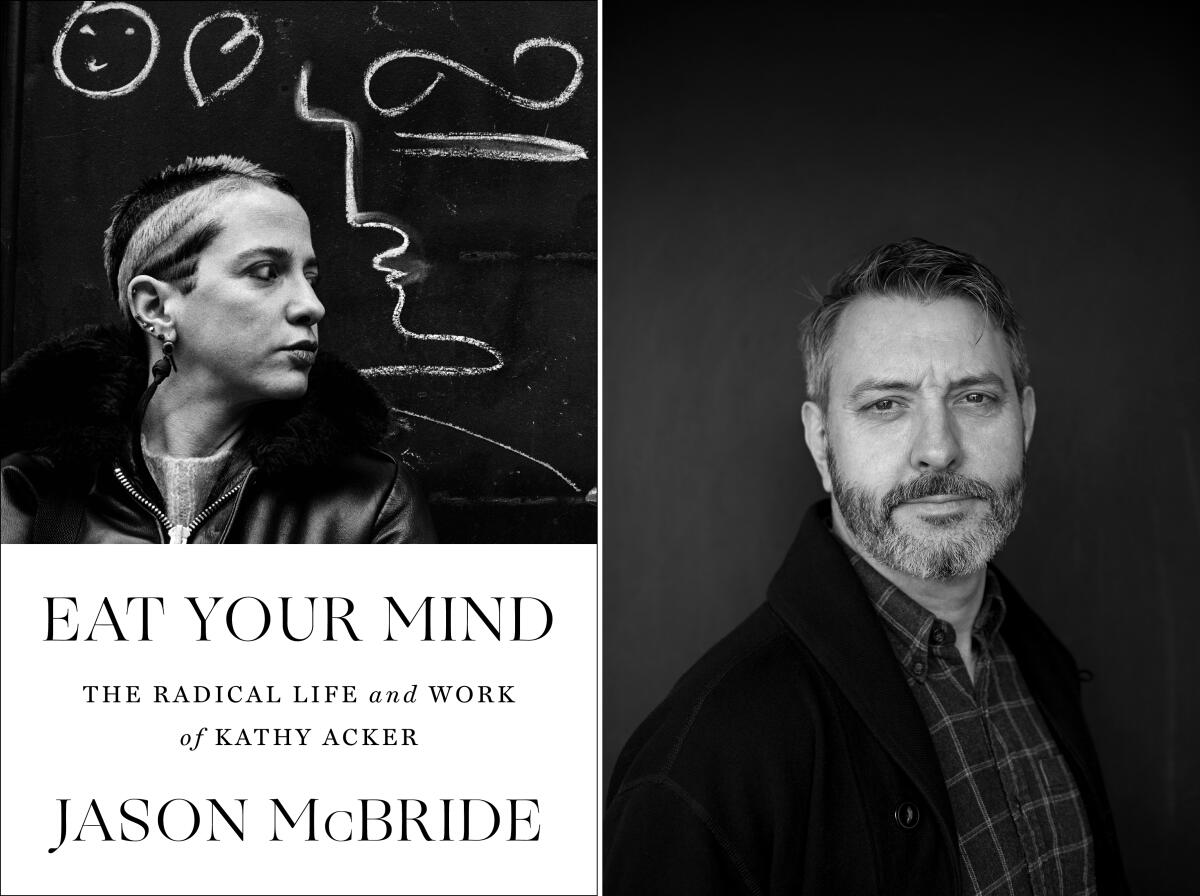

Eat Your Mind: The Radical Life and Work of Kathy Acker

By Jason McBride

Simon & Schuster: 416 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

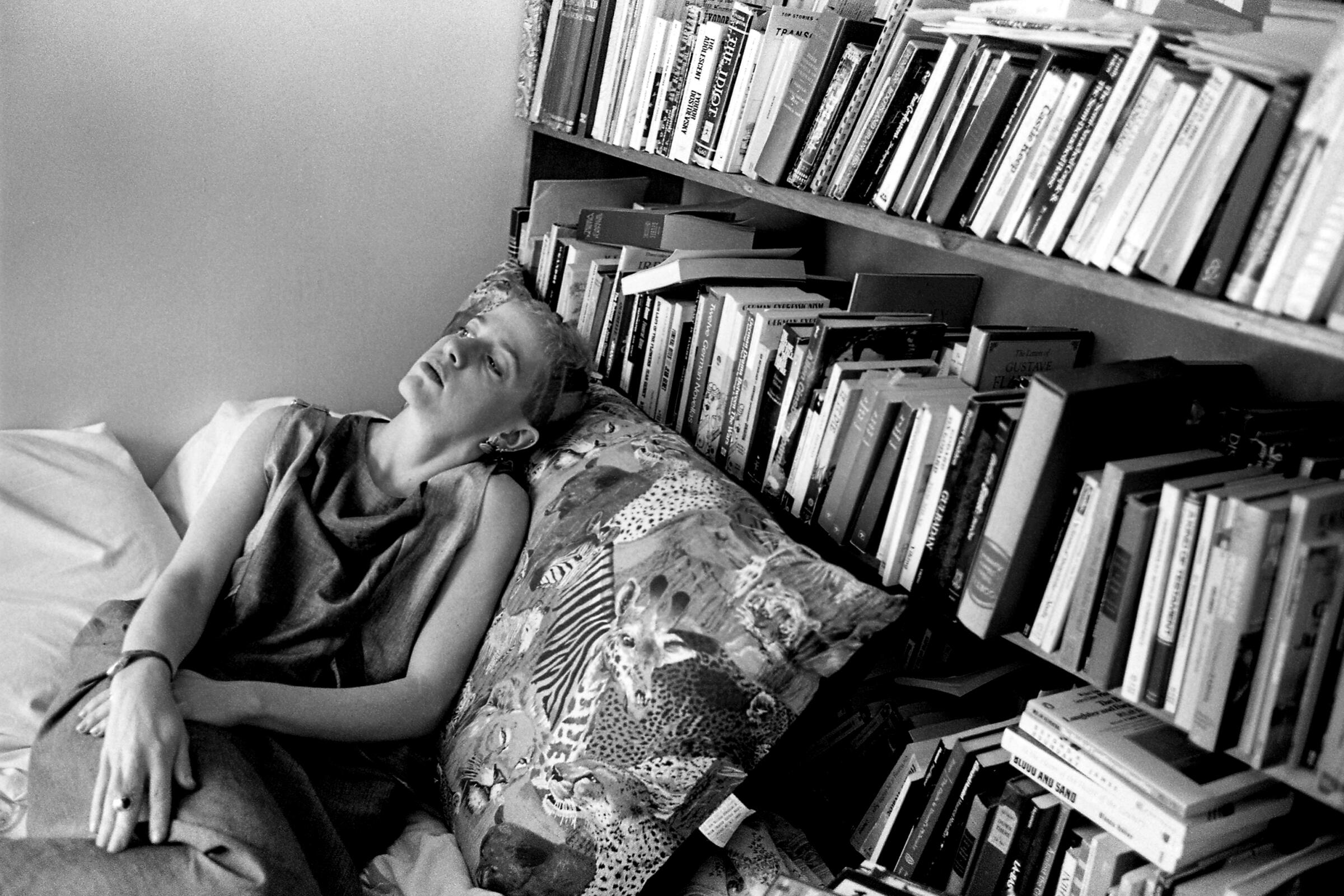

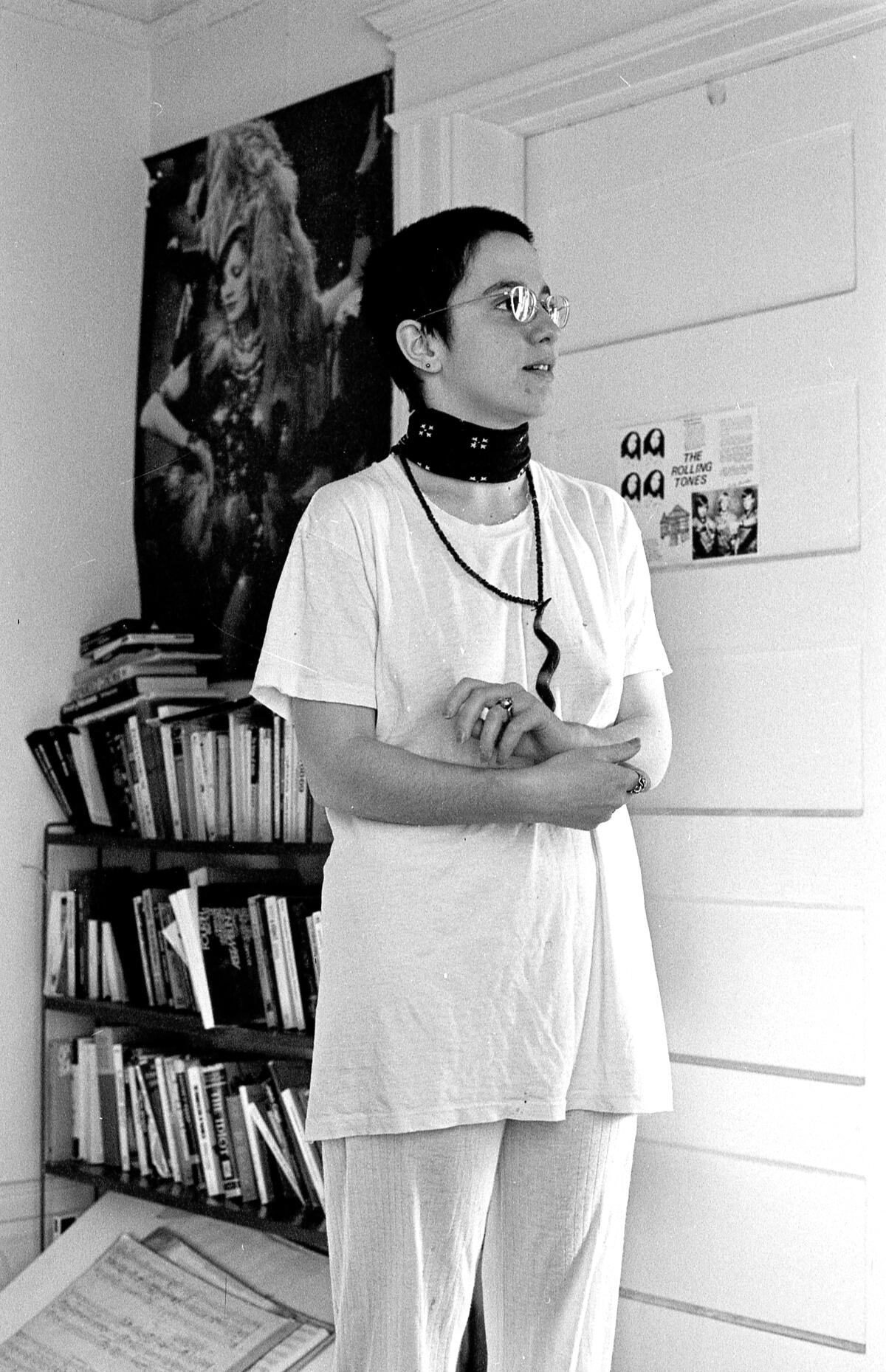

Kathy Acker is the perfect subject for a literary biography. Her work is unreadable; her allure is undeniable. She died a tragic death, from breast cancer, at age 50. She was a bodybuilder, she was a feminist — then again, maybe not. “I’m so queer I’m not even gay,” she said. She struck a fierce pose: tattooed, mounting a motorcycle. She once forced Neil Gaiman to “whip her p—.” Even in death, she is deeply intimidating.

My mom, looking through my books during a recent visit, picked up my copy of the latest book on Acker, Jason McBride’s biography “Eat Your Mind: The Radical Life and Work of Kathy Acker,” and said, “What is this about?!” What, indeed, mom.

Acker has become a small-scale personality cult. She represents a kind of deconstructivist punk empress. Her work, with its collage of classic texts and her own biography, has influenced countless writers. Her name, dropped, is a calling card. Kathy Acker is hardcore.

Growing up in New York in an “affluent” neighborhood with a mother who concealed their Jewishness and the fact that her husband had walked out the moment he learned she was pregnant, Acker performed toughness from a young age. She was “from the streets,” even if those streets might have been the Upper East Side, where Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller were neighbors. Especially after the death of her stepfather, the family’s affluence was far more precarious than it seemed. On Christmas Eve 1978, with less than $30 in her bank account, Acker’s mother checked into the Midtown Hilton and took her own life.

When Bob Dylan becomes most fully Bob Dylan, switching religions and spinning violent fantasies, it’s art. When female artists do this, it’s unhinged. Yet, like Dylan, Acker wasn’t on this Earth to make friends. “She was such a c—,” Eileen Myles tells McBride. “But the fact is, she got up every f— day and wrote. It was her religion. That’s why she was here. That’s awesome. That’s awesome for a woman. It’s awesome for a woman to say, ‘I have that,’ then deliver.”

Eileen Myles, the scholar, author and UC San Diego professor emeritus, gathers up ‘Pathetic Literature’ across the centuries and curates a new genre.

McBride is a card-carrying member of the Acker cult. But he’s also ready to acknowledge her problematic moments, of which there were more than a few. Acker once called poets “the white N—s of this Earth” and described herself, being Jewish, as a “woman of color.” McBride plays interference: “Empathy has its limits; it can be misguided. All trauma is not created equal,” he writes. “But Acker herself never really acknowledged this, and refused to let it impinge on her freedom as an artist. For someone who only ever saw fixed identity as a trap, this isn’t surprising.”

The personal is political, sure, but oftentimes the biographies of female artists are too eager to make the monster into a victim. McBride resists this through speaking to those who knew his subject and aren’t afraid to be frank. Acker was so doggedly determined to be a writer, you get the sense she would rather marry a guy than work a job that was beneath her (she married twice). “My last job was selling cookies,” she said. “It was so bad. I was 31 and said, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ Sentences out of my mouth for hours: ‘What cookie would you like?’”

It’s shocking to learn that this is McBride’s first book. He’s magnanimous when it comes to Acker’s critics, and he can paint a picture of New York’s queer art scene almost as vividly as Cynthia Carr in “Fire in the Belly,” her biography of the artist David Wojnarowicz. But Carr was one of Wojnarowicz’s friends. McBride never knew Acker.

“Eat Your Mind” effectively interlaces Acker’s books with the events in her life. Even more crucially, it places her in the grand scheme of letters, tying her ideas to predecessors including Julia Kristeva and Hélène Cixous; to contemporaries such as Myles and Lynne Tillman; and to those who’ve come after her, Kate Zambreno and Sheila Heti among them. Acker received some pretty harsh reviews in her lifetime, reviews that claimed her work had “nothing to offer,” called her writing “nasty and cantankerous.” It’s not a stretch to compare this line of criticism to the reception of contemporary novelist Ottessa Moshfegh. “She’s a different kind of writer,” the late Sylvere Lotringer said of Acker. “She became a writer in spite of writing.”

Lotringer was best known as the founder of the influential magazine Semiotext(e) — as well as for being name-checked in Chris Kraus’ ‘I Love Dick.’

I think what Lotringer meant is that Acker had something to say and her struggle was figuring out how to say it. As Myles puts it, “She was on a climb.” Scholar Avital Ronell said, “Like many writers ... she had that narcissistic motor. That meant, if it wasn’t on her GPS, she didn’t want to hear about it. She didn’t want to be stalled or slowed down.” And McBride, for his part, writes, “She didn’t know that time was running out, but then, she’d always lived as if it were.” Some of the fascination we have with certain late artists concerns the question of who they could’ve been, or what they would’ve achieved, had they lived longer.

Things did get weird at the end for Acker. A friend, sensing she wanted “touch,” felt Acker up on her deathbed, after which she “kissed the air.” After she was cremated, some of her friends ate her ashes. “They were delicious,” Kevin Killian said, “I felt her energy entering my body.”

It’s easy to want a piece of the creative action without the baggage of the artist themselves. Narcissism, ambition and flagrant disregard for others in service of art is perhaps only enviable in the abstract. Particularly when it comes to women. Tillman thought she and Acker were friends, but, “you were always Kathy’s friend,” Tillman said. “She was never your friend.”

“Eat Your Mind” does everything a good biography should and more. McBride reminds us that there’s something deeply romantic, still, about the costume of the artist that Acker wears so well. For readers and consumers, that performance is enticing. For the artist performing, it can be destructive. “Writing is one method of dealing with being human,” Acker writes in “In Memoriam to Identity,” “ ... in order to write you kill yourself at the same time while remaining alive.”

Kate Zambreno’s process is rumination and frenzy. That’s how she completed “To Write as if Already Dead,” an homage to the late writer Hervé Guibert.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.