In a Korean author’s U.S. debut, uncanny pleasures rear their ugly heads

- Share via

Review

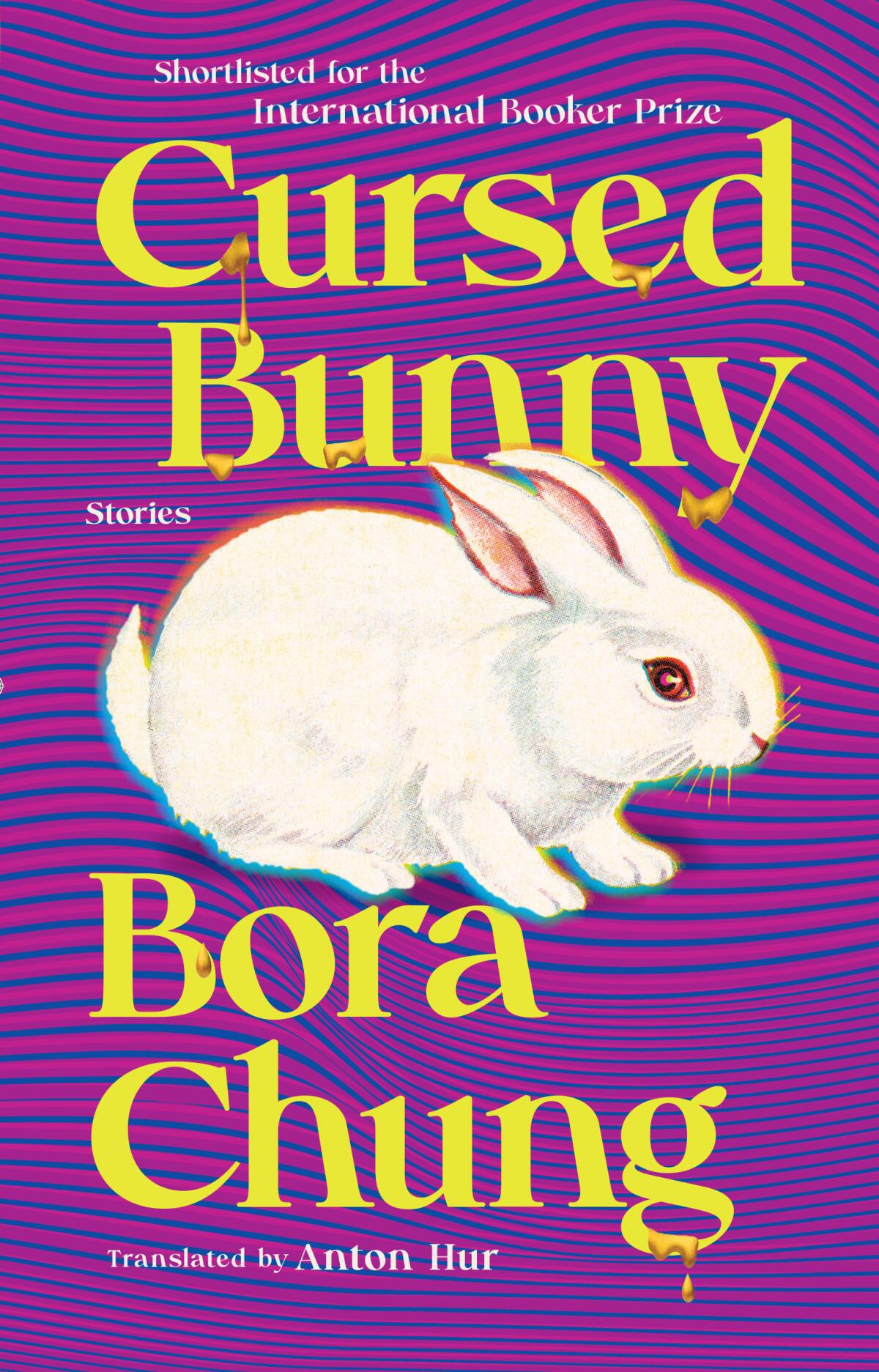

Curse Bunny: Stories

By Bora Chung

Translated by Anton Hur

Algonquin: 256 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Over the last couple of decades, literary fiction has increasingly unhinged its jaws to gulp down genre fiction, creating new, lumpy hybrids — Stephen Graham Jones’ bloodily stitched together literary slashers; Susanna Clarke’s magic potion of epic fantasy and realism; Kate Atkinson’s sliding doors of historical fiction and time travel.

South Korean novelist Bora Chung’s first translated work, the short story collection “Cursed Bunny,” is an example of the new amalgamated norm. Drawing from Korean folk tale and Chung’s expertise as a Slavic literature professor, the narratives here shamble and ooze across a porous divide between highbrow absurdism and lowbrow jump scare. The balance changes from story to story, and sometimes the genre conventions feel too pat, as genre conventions will. But the more predictable moments set you up to miss a crucial step and fall right into the abyss when Chung gets weird.

Over the course of the collection, Chung dabbles in science fiction, fantasy, fable and horror. The last is her most typical mode. She’s especially fond of an EC Comics/”Sixth Sense” style twist, in which you learn that an important character is dead, or a ghost, or unreal. Chung uses that trick in half of the 10 selections here — enough that it ceases to be a shock and starts feeling like an irritant or a cop-out. Rather than disorienting you, the last-minute flip of narrative reality becomes so expected it’s almost comforting. As in (the less interesting versions of) genre, you know what’s coming.

Chi Tai-we’s ‘The Membranes,’ finally out in English, is dated as sci-fi, but its mind-bending narrative was a prescient exploration of identity.

The sense of tropes clicking into the usual places is perhaps strongest in “Goodbye, My Love,” a story about an android companion that does what any “Frankenstein” reader would expect a story about an android companion to do.

Less rote, but also well within genre expectations, is the title story, narrated by the youngest member of a family that makes cursed objects and sics one of them on a greedy villain. The rabbit of the title is an ensorcelled lamp, which wreaks vengeance as ruthlessly and inevitably as an on-screen assassin — albeit with less slashing and more nose-wriggling. As in assassin stories, the instrument of vengeance must also suffer; in the end, the narrator expresses satisfaction in knowing their family line has no heir: “In this twisted, wretched life of mine, that single fact remains my sole consolation.” The story concludes with the satisfying click of a bunny-light going out, or a trap closing.

The expected conclusion has its pleasures. But Chung’s writing is stronger when she leans toward literary fiction’s more open forms and pursues odder ends. In “The Head,” a young woman finds a disembodied head in her toilet, which claims to be the product of her waste. In “The Embodiment,” another young woman takes too many birth control pills and ends up becoming pregnant.

In both these stories, as in Kafka, there’s horror in the initial setup. But (also as in Kafka) what’s really disturbing is the way that others — family members, doctors, passersby — treat the nightmare as normal. It’s a kind of mass gaslighting, in which women are blamed for their fear, confusion and disgust. “You’re the one who overdid it with the pills; it’s your own fault,” an obstetrician snaps in “The Embodiment.”

Similarly, in “The Head,” the woman’s family tells her to just ignore the half-formed thing in the toilet that calls her “mother.” She works to do that for practically her whole life, which in the story becomes a tedious journey from toilet to toilet. Women, the story implies, are treated —and encouraged to treat themselves — like waste. “What have you given me besides your feces and trash?” the head asks. Even anger is just more abject excess, to be flushed away uselessly and memorialized only by a shiver of disgust.

Five authors of Korean thrillers you should be reading: You-Jeong Jeong, Un-Su Kim, Young-Ha Kim, J.M. Lee and Hye-Young Pyun

“The Head” has the feel of a literary classic, unfolding with the focused power of a myth. Wonderful as it is, though, I don’t think it’s the high point of the collection. That would be a 50-page long story called “Scars.”

“Scars” opens with the kidnapping of a nameless child, who is tossed into a cave. There he is ravaged by a bird-like monster that sinks its beak into his spine to feed, leaving behind hideous triangular scars. The boy grows up in the lightless void before managing to escape. But he’s immediately captured by an unscrupulous bald man who has him fight rabid dogs in an arena. From there … well, things don’t get any better.

“Scars” is reminiscent of Amos Tutuola’s “My Life in the Bush of Ghosts” — a picaresque hallucination in which one horror stumbles into another in a jumble of supernatural confusion. But it is in the end comparable to nothing else: a sealed, sprawling mess of a story, with elements of folk tale, dream and traumatic memory, told in straightforward prose that makes the fantastical cruelties feel both more vivid and more unreal.

“The strangers who stole his childhood with their sorcerer and beliefs, the despondent life he had lived on the brink of death, it had all been meaningless in the end,” the protagonist realizes toward the story’s conclusion. Genre’s utility for literary fiction lies partly in its ability to add structure, propulsion, meaning. But mixing modes and influences can also cause electrifying static, breaking down the formal expectations of both pulp and literature with more highbrow aspirations. From the resulting meaninglessness, with the landscape cleared of obvious paths, “Cursed Bunny” at its best sets out across the rubble to find new ground — and nibble it away.

Bethanne Patrick’s December standout books include a Gen X caper, a wild adventure tale and surprising new novels from Jane Smiley and Cormac McCarthy.

Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.