How 2022’s Booker Prize winner managed a whirlwind novel and a roller-coaster year

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

By Shehan Karunatilaka

Norton: 400 pages, $19

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

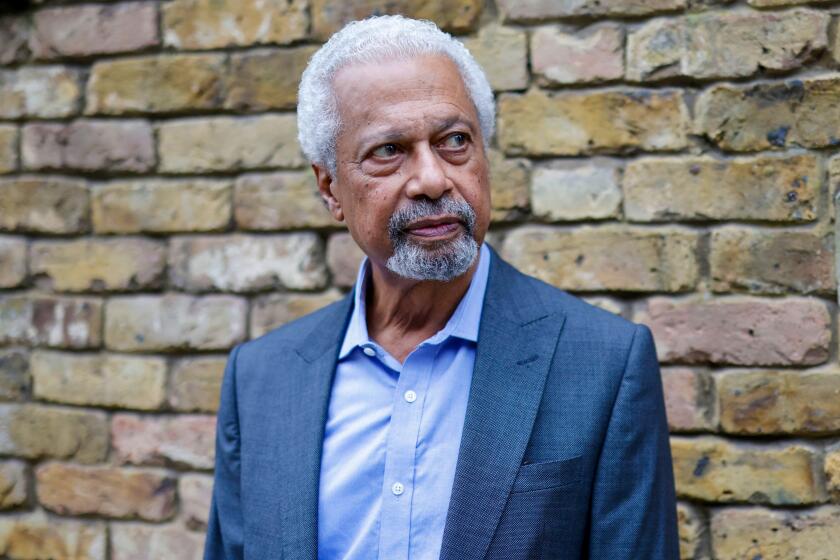

The year 2022 is one Shehan Karunatilaka won’t soon forget. The author is only now beginning to catch his breath after a journey that began by watching his native Sri Lanka explode from afar and culminated in winning the Booker Prize for his novel “The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida.”

It was a fitting story for a book that offers a roller-coaster ride through Sri Lankan history: Maali Almeida, the garrulous narrator, has a unique perspective on the conflicts ravaging his nation in the late 1980s. In fact, he’s just been murdered. And though his body has sunk to the bottom of Beira Lake in the capital of Colombo, his spirit hovers over the war-torn island, looking down on the crimes, massacres and sinister machinations haunting the country.

“How ugly this beautiful land is,” he thinks. And there’s a lot for him to take in: There are the Tamil Tiger separatists, government death squads, Marxist insurrectionists, Indian Peace Keeping Forces (which aren’t so peaceful), Chinese and Israeli arms dealers — the list goes on. The question is: Who among these factions would want to kill Maali, a freelance war photographer who sold his work to the highest bidder but refused to take sides? Sadly, more people than he thought.

‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ author Shehan Karunatilaka is the second Sri Lankan-born writer to win the Booker Prize, after Michael Ondaatje.

Racing against time — he has only seven days, or moons, before his soul is dispatched to a final realm of the afterlife — Maali frantically tries to solve his own murder while guiding loved ones to a stash of photographs that “could topple the government.” The manic driving force behind this philosophical and political mashup, Maali is a mass of contradictions (like his country). A “devout atheist” and cynic, he has an almost religious faith in the power of journalism. A chronic gambler and carouser, he’s also a closeted gay man who feels most at home in war zones far from Colombo’s urban bubble.

Karunatilaka’s first novel, “The Legend of Pradeep Mathew” (2012), was a critical success, but it was set in a milieu — professional cricket — alien to most American readers. He envisioned his second book as something more accessible: a ghost story. Originally titled “Chats With the Dead,” it began with the idea of a photojournalist speaking with victims of Sri Lanka’s civil war, which had ended in 2009 and was still a raw, hotly debated subject.

“My thought was, ‘What if we could interview some of the dead people? Maybe they could shed some light,’” Karunatilaka says over Zoom from his home in Colombo, happy to be “back at the desk in this messy room where I belong” after his Booker media whirlwind. “What was frustrating to me was that we weren’t … looking at the causes” of the war. “We were arguing over whose fault it was.”

As a teenager in Colombo in the 1980s, Karunatilaka was exposed to the daily violence firsthand, though he was mostly insulated from even greater terrors in other regions. He recalls the sight of bodies on the side of the road, hanging in tires and on fire. “I just remember 1989 as being conflict after conflict,” he says. “And that’s why I leaned on the supernatural: What’s the explanation for all these conflicts we’re embroiled in? Could it be that there are spirits and demons and angry ghosts swirling around whispering thoughts in ears?”

The more he wrote, the more complicated the novel became. “It was a handful already: I had a murder mystery, a supernatural story, and a political backdrop based on reality,” he explains. “If I wrote this as a thriller, anyone would say there’s way too many plots here.” Working closely with his U.K. editor, Karunatilaka tinkered with the novel during the pandemic, paring it down and clarifying the maze of political and mythological references. He took his editor’s advice to heart — “We don’t want all the instruments playing at once,” she reminded him — and together they ended up performing “surgery” on the book.

Much of the world may consider him obscure, but to generations of writers with African roots, Abdulrazak Gurnah is both an influence and a role model.

One thing they didn’t tamp down is Karunatilaka’s exuberant language and gallows humor, which seem to borrow in equal measure from Salman Rushdie and Kurt Vonnegut. And while other Sri Lankan writers have written eloquently about the country’s past — Michael Ondaatje, Romesh Gunesekera and Anuk Arudpragasam among them — Karunatilaka says he feels more indebted to the nation’s pulp and comic literary traditions.

“I don’t know really where I fit in,” he says with a shrug. “This sort of absurdist take on things — it just seemed truer to Sri Lanka. It’s not a dour place. This kind of humor in the face of grimness, I think, is mainly the Sri Lankan sensibility. It certainly is mine.”

A sense of the absurd also helped Karunatilaka cope with his strange year. In May, he was at a writing residency in Iowa when Sri Lanka erupted. There were power blackouts; food and fuel shortages; protests engulfing the streets. Crowds set fire to the prime minister’s house and the president ending up fleeing the country. “You look at Sri Lanka in 2022 and scan some of the headlines and images, the jokes and memes, and you can see there’s a lot of ridiculousness even though it can be quite grim and depressing if you allow it.”

Karunatilaka was “following the revolution on Twitter,” he says, when he attended PEN America’s Emergency Congress of Writers at the United Nations that month. “I was listening to them talk about Ukraine and Palestine and the climate crisis and I was like, ‘Wait, is no one going to mention that this country is on the brink? Don’t forget this tiny country, Sri Lanka.’”

Then came good news: In July, his novel was longlisted for the Booker Prize; in September, it made the shortlist. At the Booker ceremony in London in October, Karunatilaka was the surprise winner. (As a gambling man, Maali Almeida would’ve appreciated the odds: Elizabeth Strout was the favorite at 3-to-1, Karunatilaka close behind at 16-to-5.) After a stressful year for his country — political and economic collapse followed by a humiliating cricket defeat by Namibia, no less — Karunatilaka hoped all of Sri Lanka could celebrate his award.

Galgut’s ‘The Promise’ tracks a fictional family as South Africa evolves. He talks to The Times about what his victory means for him and for Africa.

“I didn’t want it to just seem like a win for English-speaking, middle-class Colombo writers,” he says. And so, at the end of his acceptance speech, he felt “it was important” to say a few words in both Sinhalese and Tamil. “I didn’t say much, I just said in Sinhalese that it’s a victory for the whole country. And in Tamil, I said as Sri Lankans, let’s share our stories. Let’s listen to each other’s stories, hear each other’s stories.”

He lets out a sigh, still reeling from the experience. “What a year it’s been, I have to say. Really, one for the memoirs: Iowa, country implodes, get a Booker longlist and then the prize and now I’m here.” He pauses. “So, yeah, I’m looking forward to Christmas and just chilling on a beach.”

Tepper has written for the New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.