Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

On the Shelf

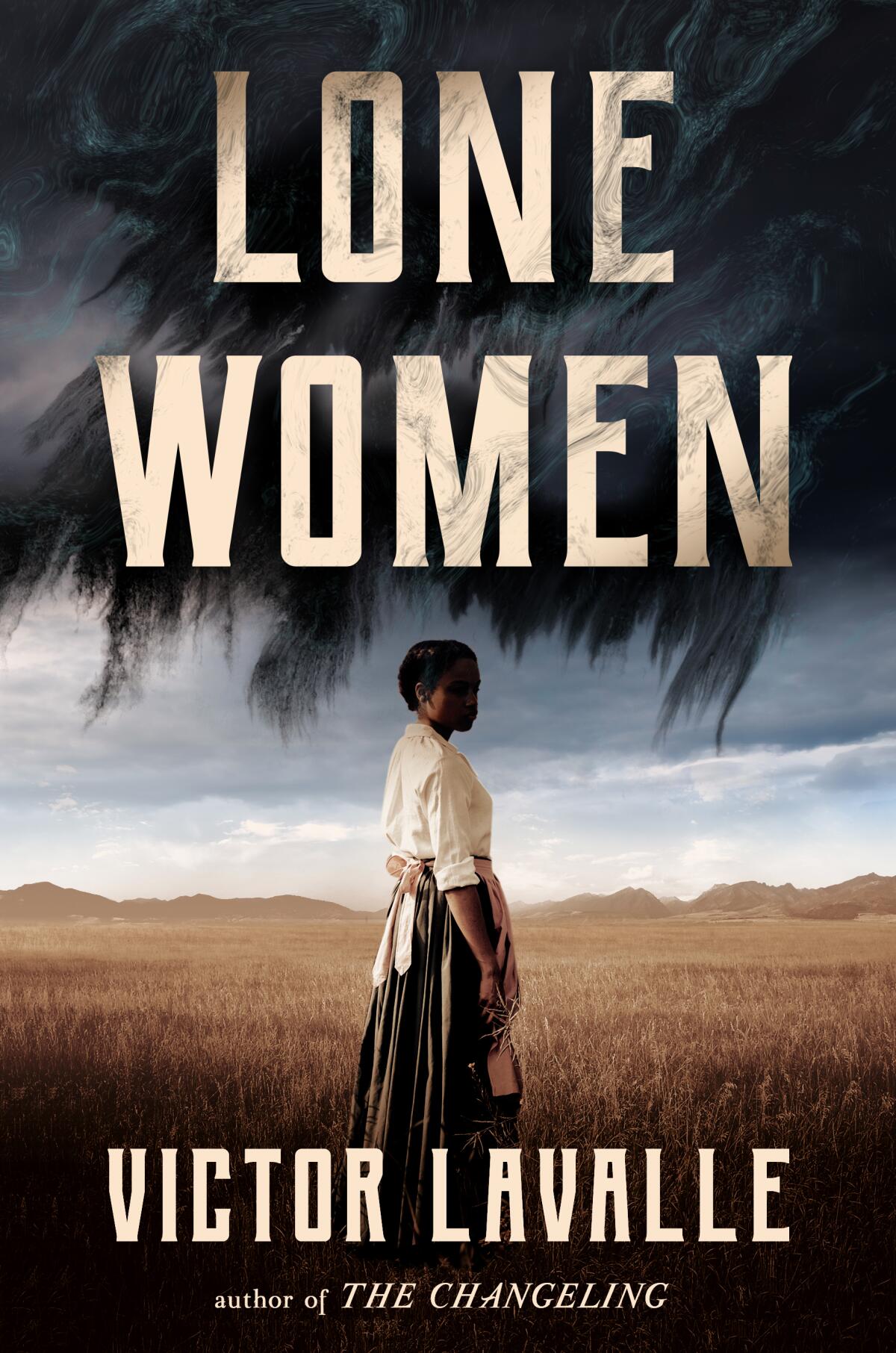

'Lone Women'

By Victor LaValle

One World: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“History is simple, but the past is complicated.” says a character in Victor LaValle’s new novel, “Lone Women.”

In telling the story of single women who settled in early 20th century Montana, LaValle complicates traditional narratives of American frontier life. Consider it a variation on the theme of his life’s work. Over more than two decades, the author has won acclaim and devoted fans for mostly New York-set novels that subvert literary fiction by blending in horror and fantasy. His previous novel, 2017’s “The Changeling,” dove deep into internet culture, book collecting and parenthood with the complication of a possibly demonic baby. (It will soon become an Apple TV+ series.) “Lone Women” is a bit of a departure, though not as much as you’d think.

It started, LaValle told me via Zoom last month, during a trip to the University of Montana, where he bought a book: “Montana Women Homesteaders: A Field of One’s Own,” edited by Sarah Carter. “I was fascinated by all these women who went out [to Montana] to try on their own. I found out there was at least one Black woman homesteader, and that the Chinese population couldn’t homestead,” due to immigrant exclusion laws.

Katie Hickman’s “Brave Hearted: The Women of the American West” features pioneer wives, trafficked immigrants and a heroic Black midwife, among others.

The result is Adelaide Henry, a Black, single woman who flees California after violence claims her parents. “There are two kinds of people in this world,” LaValle writes by way of introduction: “those who live with shame, and those who die from it.” Adelaide sets out first to Seattle to sign a claim, then journeys to Montana. Traveling solo, she bears only what she needs for her new life, including a heavy, locked trunk. Readers sense immediately that this is some kind of anchor chaining her to her past — and also something like the Ark of the Covenant, inspiring dread of the horrible truths it might reveal.

A western with horror trappings, “Lone Women” is also set on revisiting — and revising — that complicated past. “One of the things I wanted to get across,” LaValle says, “is that the tenor of a lot of old westerns is, ‘Look how bold and brave these white men with the law and the government and guns all on their side were.’ And I wanted to say, ‘That’s not brave. What’s brave is to go out there when you know all those things are allied against you.’ I was astounded by the bravery of these women.”

To depict them, LaValle drew on a family history forged by pioneering women of a different era. His mother fled Uganda’s repression, arriving in Canada and then New York.

“As I get older, a parent and a working person also,” LaValle says, “I think back to my mother coming to New York in her 20s in the late 1960s. Things are rough, not so great, but she finds a way to make it here. She has me in 1972, and things don’t work out with my dad. Eventually she gets my grandma over here. And the idea of just the two of them in New York felt to me very much like the energy of homesteading. The same boldness at leaving everything behind. I was trying to channel my admiration and love of the two of them into how I thought of Adelaide and the other lone women.”

Unlike many children of immigrants, LaValle says he was never pressured to follow a professional career path. His mother supported the family as a secretary, “but she was an artistic soul.” She painted, sculpted and played the piano, which gave him freedom when he decided he wanted to be a writer at an early age.

LaValle still faced hurdles; college at Cornell University was a struggle. “I was a mess, trying to keep my nose above water,” he says. One dean insisted he would never be allowed to graduate. But after taking a leave, LaValle persevered.

What really inspired LaValle was all of the reading he did as a kid. “The corner store was run by two sisters named Gina and Rose. And they would let you read comics on the spin rack as long as you bought something else. They had the energy of being aunties for all the kids.”

After comics, he remembers reading Poe. “But like many folks of my generation who love horror, it was Stephen King, who I was reading when I was 10, 11 or 12. Part of his genius was that he could write in a way that, as a kid of that age, I could get it. But an adult could read it and understand the deeper subtext.” From there, it was on to Clive Barker, Peter Straub, Shirley Jackson.

Alex Segura’s “Secret Identity,” about a Latina who invents the Legendary Lynx and moonlights as a PI, is the unlikely culmination of a life spent in love with genres.

“Lone Women” incorporates some of the genre tropes that infused “The Changeling,” as well as another LaValle novel, “The Devil in Silver,” about a mental institution where patients were stalked by a monster. (A screen adaptation is in development.) But the new book is not horror per se; it’s more a novel haunted by the unseen specter of horror. And, in another departure for LaValle, it’s shot through with a strain of optimism. He owes that to another strong woman, his wife, the writer Emily Raboteau.

“It was during the Trump era, and so there was already a war on women happening,” LaValle recalls. “And she said, ‘It’s hard enough. I want to read this book and be happy for the women.’ And I said, ‘OK, Darling. Let’s do it.’ And then it was fun. It was actually very freeing because I knew this isn’t what you would expect to happen” in a Victor LaValle novel, he says.

The author also sought feedback from his agents, both women. They advised him on moments when a woman would be vulnerable in a way a man might not see. Raboteau, meanwhile, would talk him through what he was getting wrong. “The funny thing was that sometimes my solution would be that she would just beat up whoever. And my wife would say, ‘Shut up.’”

Not that Adelaide couldn’t deliver a beat-down. Thinking about the physical strength it would take to cut down trees and work the land, LaValle made her a physically formidable woman. She and other characters, like the inimitable Bertie — who makes a “special brew” in high demand — are not waifs of the frontier. Sometimes, LaValle confesses, he wanted the reader to witness Adelaide in a confrontation and think, “Could she kick that dude’s ass?”

We laugh, but it leads us back to the topic of how “tough” women are often portrayed. ”I don’t enjoy modern-day films where there’s scenarios with 10 soldiers in a room, and a small woman, some actress that weighs 105 pounds — and then she beats them all up,” he says. “I would love to see you have to think through how this particular woman could beat them without having to fight like Arnold Schwarzenegger.” He admits he was tempted to choreograph more fight scenes — before reminding himself he wasn’t writing an action movie in which physical violence was the expedient choice.

Cai Emmons, a prolific novelist of the West, died Monday, after running a blog after her ALS diagnosis that has much to teach us about facing the inevitable.

It’s just one of many ways LaValle was looking to turn the western inside out. The heroism of the lone hero in unspoiled wilderness is replaced by the sense of a place marked by absence: the expulsion and incarceration of Native Americans; the exclusion of would-be immigrants. One of the toughest challenges for LaValle was deciding whose stories to tell — and which he had to leave out.

“I wondered about the variety of characters, and the comfort I felt with who might show up or not show up,” he says. “There is a Métis trader who comes in, which also shows the porousness of the Canadian border at the time. I wanted the characters to acknowledge this history, not only that Native peoples were there, but explicitly talk about how we — the characters — pushed them off. How all of these underdogs also have underdogs. It was my hope to acknowledge the layers.”

One medium that allows for more play and more inclusion is television. LaValle is relishing the adaptation process on projects in development, especially “The Changeling.”

Kelly Marcel, showrunner of the “Changeling” Apple series, has worked to expand the source novel’s narrative. “Kelly was such an amazing collaborator,” LaValle says. “Right from the beginning, she said she wasn’t going to change the book — she was going to add to it. She saw that the book was told from the character of Apollo, the main character. And she told me that she wanted a lot more room for Emma’s character…. There are these moments of love and camaraderie between the women that’s lovely stuff.”

This, at least, is nothing new for LaValle, who knows he’d never have gotten here, to the top of his game, without women.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.