Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

On the Shelf

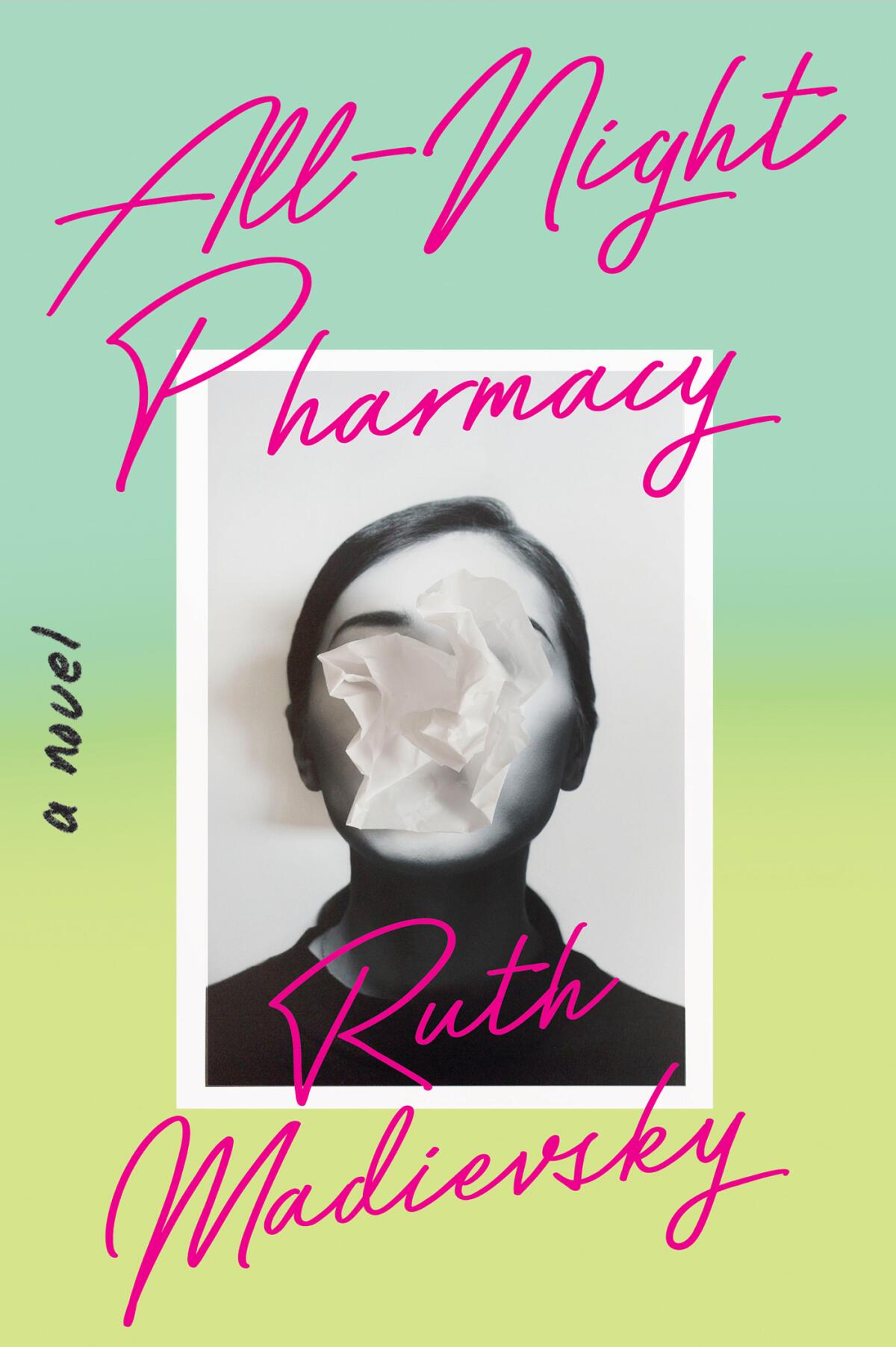

'All-Night Pharmacy'

By Ruth Madievsky

Catapult: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Ruth Madievsky doesn’t seem to have a high tolerance for risk.

Sitting at her dining room table in her tidy Santa Monica apartment, the author exudes serenity as she discusses juggling her job as a clinical pharmacist with her writing career while her 3-month-old infant naps in the next room.

You’d never guess that the characters in her debut novel, “All-Night Pharmacy,” blaze a trail across L.A.’s bar scene under a haze of benzos, opioids and psychedelics, risking death or degradation at every turn.

“Whenever I’m asked if the drug use is fictional,” Madievsky tells me, “I always say, ‘It’s fictional! So fictional!’”

Madievsky does draw on her knowledge of pharmaceuticals to paint a realistic portrait of what it’s like to have one’s life go off the rails due to destructive drug use. In her intimate tale of two sisters, the unnamed protagonist is alternately compelled and repulsed by the toxic narcissism of her older sister, Debbie, a wild child who works in a strip club and is “so alive it was scary.”

David Sanchez lived a lifetime before he went sober at 20. He describes the frantic and healing process of pouring it out into ‘All Day Is a Long Time.’

Under Debbie’s influence, the younger sister embarks on an odyssey of questionable decision-making — from shacking up with a guy she meets at a bar to cooking up a scheme to peddle pills scammed from the clinic where she works.

The sisters haunt a club called Salvation housed in what used to be a Christian bookstore, where their favorite pastime is roping strangers into playing a game called Wealthy Patron, in which participants confess to how much money they would accept in exchange for engaging in degenerate behavior. As the novel progresses, the deeds get dirtier and the price gets cheaper.

Although “Pharmacy” crackles with the energy of Hubert Selby Jr.’s “Requiem for a Dream” or Patrick deWitt’s “Ablutions,” Madievsky’s knowledge of drug lore is strictly professional. She would like you to know she has no experience dealing Class A drugs, and she has a few other misconceptions to clear up about her profession: She does not count pills, nor does she work in a CVS. She works in a clinic with patients she sees on a regular basis. Her specialties are HIV and primary care.

“It’s very rewarding,” Madievsky says, “because I’m helping to make people’s lives better and it’s really nice for my writing, too, because if I have a [crap] writing day, at least I know that I did something good in the world.”

She does worry colleagues might take her writing the wrong way. (Madievsky has also published a poetry collection called “Emergency Brake.”) Or, more specifically, she worries that regulators at the California State Board of Pharmacy might conflate her characters’ predilections with her own lifestyle choices.

In part, that’s due to the fiction’s high level of verisimilitude — from L.A.’s dives and ratty apartments to the predictable patterns of addiction. “I really didn’t want to write about anything that either I hadn’t personally experienced or people that I was in community with hadn’t experienced,” Madievsky says, “because I feel like it’s so easy to do harm if you’re conjecturing about what a [marginalizing] experience is like.”

In advance of the 2023 L.A. Times Festival of Books, we surveyed 95 writers and culled 110 works into the Ultimate L.A. Bookshelf. Get ready for some surprises

Yet the novel is more than an L.A. drug story. The relationship between the two sisters is just one of the book’s many threads, which include the narrator’s fraught dealings with her mother, who experiences a series of mental health crises related to the horrors her parents endured in the former Soviet republic of Moldova. The novel also explores the eroticism of the narrator’s first same-sex relationship. And it takes a darker turn when Debbie goes missing.

“It’s a detective novel. It’s an immigrant novel. It’s a queer coming-of-age novel. It’s a sisterhood novel. It’s just like when you go to a pharmacy,” Madievsky says. “They have everything.”

Hence the title, which was suggested by a friend. Originally it was “Prescriptions,” “which I thought was so clever,” Madievsky says, “because it has a double meaning. It’s both medication and advice, and the narrator is constantly seeking counsel on how to be a person.”

Despite the multifariousness, “All-Night Pharmacy” is not a shaggy dog story. It pulses with intensity as its characters struggle to find their way. The taut narrative is driven by Madievsky’s razor-sharp prose, which she attributes to her background as a poet.

“I bled over every word, every description,” Madievsky says, “because I feel like when you’re writing poetry, the pursuit of beauty trumps anything else. You can abandon any form, any narrative in pursuit of something that feels true, even if it destroys everything that came before.”

There are passages in “Emergency Brake” that anticipate the novel. In the poem “Halloween,” the narrator endures a night out at a bar with her boss while her mind drifts like a clairvoyant Molly Bloom on benzos:

“…all my life / I’ve been about as carefree as a soft peach / in a pile of broken glass, my hand / always twitching toward the Ativan bottle.”

From Boyle Heights to Filipinotown to the Autry Museum, venues are hosting poetry readings again, restoring a vital link between artists and their communities.

Despite her achievements in poetry and prose, Madievsky has little formal training as a writer. After she received her undergraduate degree, she enrolled in USC’s four-year PharmD program, which was followed by a yearlong residency.

“I knew I was going to be a pharmacist — just like my mom — from the time I was 8 or 9,” Madievsky explains.

Her parents arrived in L.A. from Moldova as Jewish political refugees when Madievsky was 2 years old. She lived in an apartment near Fairfax and Santa Monica (“in the Russian diaspora district”) with her parents, her grandparents and her great-grandmother, whose husband was murdered by the KGB. Madievsky recalls growing up in a neighborhood where shop signs were in Russian and English and old men played chess in the park.

“At some point, I wanted to be a writer more than I wanted to be a pharmacist,” Madievsky confesses, but her parents insisted she get her pharmacy degree in case they had to move again and start over somewhere else. “You have to have a backup!” they told her.

In this respect, “All-Night Pharmacy” is somewhat autobiographical. The protagonist, her sister and her mother are all wrestling with the knowledge that their forebears endured unimaginable suffering so that they could prosper in the United States. This incalculable debt starts to feel like a chokehold when the sisters fail to make the most of their opportunities.

“I was interested in the ways that historical traumas affect people who are several generations removed,” Madievsky says, “and might not even know that they’re reacting in some way to those traumas.”

It’s been a broken, chaotic year in life and in fiction. Authors such as Hernan Diaz and Namwali Serpell broke their novels and heroes into pieces.

Rather than dabble in the self-destructive behavior of her characters, Madievsky has learned to channel her ancestors’ experiences as both a healer and a storyteller. Near the middle of the novel, the protagonist embarks on a journey to Moldova that has echoes of a trip the author took to her homeland.

“I have mixed feelings about using them in fiction,” Madievsky says of her family’s stories, “but my prevailing feeling is I want to memorialize them somehow, especially because every time I hear them, the stories are a little different. There’s a lot of ‘Oh, everyone who remembers is dead,’ so there’s no one to ask. I felt this responsibility to keep those stories alive.”

Ruland’s most recent novel is “Make It Stop.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.