Read The Times’ scathing, prescient review of Michael Lewis’ ‘The Blind Side’

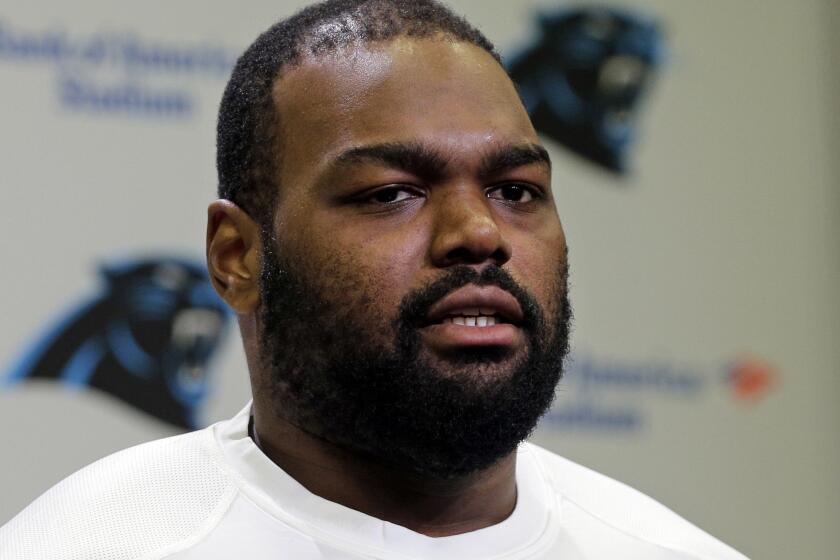

On Monday, NFL veteran Michael Oher filed a petition in a Tennessee court alleging that his caretakers, Sean and Leigh Anne Tuohy — the heroes of Michael Lewis’ 2006 book “The Blind Side” and the 2009 film adaptation starring Sandra Bullock — had never officially adopted him, instead arranging for a conservatorship that deprived him of revenue. Sean Tuohy swiftly refuted the lawsuit’s claims, defending the conservatorship and calling the suggestion that the Tuohys “enriched themselves” at Oher’s expense “insulting.”

The reception of Lewis’ book about a white couple who took in a poor, Black, talented teenager was relatively mixed for the nonfiction superstar. But Steve Almond’s scathing review in The Times now feels especially prescient. “The essential message,” he wrote, “is that poor black children matter, and are seen as worth helping, not because of the content of their characters but because of their physical prowess.” In 2014, Almond expanded on his analysis of the sport and its injustices in his own book, “Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto.” Read the full Times review of “The Blind Side” below.

Michael Oher, the NFL star whose life story was dramatized in Oscar-winning film ‘The Blind Side,’ alleges the Tuohy family tricked him into a conservatorship.

Over the last two decades, Michael Lewis has become an all-star at what the pros call immersion journalism. He is able to burrow into a cultural ecosystem, zero in on the most colorful characters available and use them to lay bare the intricacies of that world for us civilians. His bestsellers have demystified — among other exotic precincts — Wall Street (“Liar’s Poker”), modern baseball (“Moneyball”) and Silicon Valley (“The New New Thing”).

In “The Blind Side,” Lewis takes on football, and specifically the mania for the game as encountered in Southern culture. It is a riveting account, though its pleasures — like those of watching grown men nearly kill one another over a pigskin — are ultimately distressing.

“The Blind Side,” in fact, tells two stories. The first is about the ascendance of left tackle, the offensive lineman in charge of protecting valuable NFL quarterbacks from harm. The second is about the ascendance of a young giant named Michael Oher, widely considered one of the best left tackle prospects in the country.

Lewis opens with an image familiar to football fans: Lawrence Taylor, the New York Giants’ revered linebacker, delivering a (literally) bone-crunching hit on Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann in 1985. The play ended Theismann’s career. It also placed a sudden premium on finding players who could prevent such catastrophes. This task fell to the left tackle, who suddenly graduated from just another grunt in the trenches to heroic point man. Unlike many sportswriters, who tend to traffic in the immediate (and obvious), Lewis takes the long view. He traces how 49ers Coach Bill Walsh revolutionized football during the 1980s by installing a short passing game that caused the traditional emphasis on running to be outmoded. Lewis also notes how this shift in the pro market, like others, trickled down:

“The NFL would discover a passion for athletic (read: black) quarterbacks, or speedy pass rushers, and first the colleges and then the high schools would begin to supply them. There was a lag of course ... but the wave always came. What the NFL prized, America’s high schools supplied, and America’s colleges processed.”

Having established the lay of the land, Lewis proceeds to his main attraction: Oher, a painfully shy black kid from the projects of west Memphis, Tenn., who happens to be 6 feet 6 and 345 pounds. Thanks to his unusual combination of size and speed, he is accepted at a private evangelical high school, adopted by a rich white family on the east side of town and molded into an All-American.

There’s an undeniable thrill in tracking his rise from a destitute kid with no prospects to a gridiron prodigy beset by college recruiters. And Lewis does a remarkable job of describing the emotional contours of the feeding frenzy. “The wooing of Michael Oher was pure southern ritual: everyone knew, or thought they knew, everyone else’s darker motives, and what didn’t get said was far more important than what did. The men seized formal control of the process. The women, acting behind the scenes, assumed they were actually in charge.”

Lewis also documents the rule-bending done to keep Oher college-eligible. The administration at his high school accepts him although he can barely read. He secures a full-time tutor. When his grade-point average still proves too low for the NCAA, his adoptive father, a canny former college basketball standout named Sean Tuohy, manages to find a crucial loophole. He has Oher tested to prove he’s learning disabled, then has him take numerous easy, online courses. Lewis treats these measures as ingenious. We are meant to cheer the fact that Oher has gamed the educational process.

Sean Tuohy — NFL star Michael Oher’s self-proclaimed adoptive dad — defends his decision to use a conservatorship instead of adoption in their relationship.

Tuohy’s indomitable wife also plays a key role in the reeducation of Oher:

“Leigh Anne was now making it her personal responsibility to introduce him to the most basic facts of life, the sort of thing any normal person would have learned by osmosis. ‘Every day I try to make sure he knows something he doesn’t know,’ she said. ‘If you ask him, ‘Where should I shop for a girl to impress her?’ he’ll tell you, ‘Tiffany’s.’ I’ll go through the whole golf game. He can tell you what six under is, and what’s a birdie and what’s par.’”

Maybe it’s just me, but I’m not sure these qualify as the most basic facts of life. Indeed, for all her Christian charity, Leigh Anne seems to treat her adopted son more like a giant kachina doll than a human being. Oher recognizes the ulterior motives swirling around him: “He didn’t go so far as to treat Leigh Anne with suspicion but, as Leigh Anne put it, ‘With me and Sean I can see him thinking, If they found me lying in a gutter and I was going to be flipping burgers at McDonald’s, would they really have had an interest in me?’ ”

This question is never answered.

As I tore through the book, I kept wondering how Lewis got such remarkable access to the Tuohys; and I also wondered, why does he take such an uncritical view of their role? The author’s note at the end provides the obvious explanation, stating that Lewis is a friend of Sean Tuohy’s and that they had been longtime classmates at the same New Orleans school.

The Tuohys eventually persuade Oher to attend their alma mater, Ole Miss, where football players have to “go through the tedious charade of pretending to be ordinary college students” to get their shot at the NFL. Lewis doesn’t dwell on the cynicism of this arrangement, either. He is too determined to paint Oher as a heroic figure. “The world that had once taken no notice of Michael Oher was now so invested in him that it couldn’t afford to see him fail,” he insists. The problem is, that Lewis never bothers to ask why.

The essential message of “The Blind Side” is that poor black children matter, and are seen as worth helping, not because of the content of their characters but because of their physical prowess. Like most fans — myself included — Lewis prefers not to notice the prejudices that belie our lust for sport, the perverse arrangement by which watching young black men engaged in violent spectacle has become our most profitable form of entertainment. I have no doubt that this book will become another Lewis bestseller. It will play to the masses as an inspiring underdog saga, spiced with proper pieties about the power of hope and individual destiny. It should also stand as an inadvertent testament to the national blind spot that still prevails when it comes to our racial pathologies.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.