In Kristen Roupenian’s story “Cat Person,” a college student, Margot, meets an older man, Robert, at the movie theater where she works. They flirt over text messages devoid of real information, then go on an awkward date. By the time she knows she doesn’t want to sleep with him, she thinks it’s too late not to. When she breaks things off afterward, he follows and harasses her. The story ends with his abusive texts.

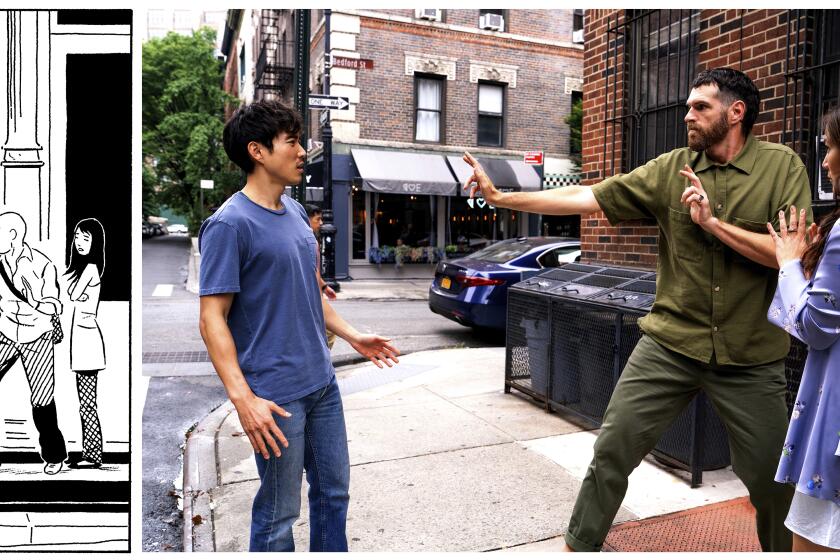

It’s an everyday occurrence, as common as a penny, though easier to avoid with experience. But a real Margot doesn’t vanish with the last sentence; she’s left looking over her shoulder. The film version out this week asks, what then? How concerned should she be, and what might she do about it? And is it possible to adapt such a bummer story into a popcorn movie without blunting its bite? Surprisingly, screenwriter Michelle Ashford (“Masters of Sex,” “Operation Mincemeat”) and director Susanna Fogel (who co-wrote “Booksmart”) find a way, making “Cat Person” charming and disturbing, humane and hyperbolic — a darkly comedic anti-erotic thriller that heeds the story’s slippery form.

The debut book from Kristen Roupenian, whose New Yorker short story “Cat Person” went viral far beyond the scope of most short fiction when it was published earlier this month, has been sold to British publisher Jonathan Cape, the Guardian reports.

The original story’s narration is in close third-person; we see each situation unfold from Margot’s point of view, interpreting with her moment by moment. When it ran in the New Yorker — shortly to become the first viral short story of the internet era — Roupenian discussed her premise with the fiction editor in an accompanying interview. “Our initial impression of a person is pretty much entirely a mirage of guesswork and projection,” she said.

Adding to this ambiguity, she went on to cite Margaret Atwood with a quote that now opens the movie: “Men are afraid women will laugh at them. Women are afraid men will kill them.” While a current of this danger runs through the story, the film’s wily third act amplifies it, raising the stakes while keeping us guessing alongside Margot (Emilia Jones, “CODA”). Fogel executes the script with admirable confidence.

That confidence is no small thing, given the baggage that comes with the story. As background for the less online (which normally includes myself), a primer on the virology of “Cat Person”: In 2017, Roupenian wrote and submitted the story, inspired by an alarming incident with someone she met online. A few months later, #MeToo took off, and the New Yorker ran “Cat Person” with a memorable photo of not-quite kissing mouths.

Younger women shared it on social media, relating to the quandary of extracting themselves from liaisons without provoking men. Older women wondered whether things have really changed. Men began to take note, some personally offended by the way the fictional Margot sees her date and incensed by the story’s success. Many who weren’t regular fiction readers conflated Roupenian with her protagonist, though the former was a 36-year old academic.

Adrian Tomine adapted his graphic novel ‘Shortcomings’ into a film directed by Randall Park, resulting in an effective, at times transgressive rom-com

In 2021, with the pandemic full-blown and the film version in development, a young woman published an essay in Slate about her recently-deceased ex-boyfriend — identical to the story’s Robert. Roupenian told her she’d had an encounter with him, then learned from social media that he’d dated a local undergrad who worked at an indie cinema. Now the young woman wanted to set the record straight: Really, he hadn’t been a bad guy; they’d actually dated for a couple of years — starting when she was in high school.

The film rises to the challenge of this chaotic legacy. It also honors the author’s work in playful ways. While the story detailed a regular instance of hetero dating, ordinary enough for thousands to make theirs, Roupenian’s home as a writer is horror. She’s named Stephen King and Shirley Jackson as her heroes; monsters and macabre twists proliferated in her debut story collection, “You Know You Want This” (newly reissued as “Cat Person and Other Stories”). When Ashford and Fogel consulted her, she was reportedly delighted to see them lean into the story’s genre potential. Her interest was to explore Margot’s uncertainty — a natural part of getting to know someone, but also the state most crucial to movie suspense.

The script is rich with allusions to cultural tropes around sex and predation, from the opening cries of an exploitation film playing at Margot’s workplace to a sinister Lee Hazlewood song over the closing titles. Margot’s roommate is starring in “Into the Woods,” Stephen Sondheim’s satirical take on fairy tale romance. Isabella Rossellini plays on her recent ethology series (“Green Porno”) as Margot’s anthropology advisor, whose special interest is fatal mating rituals in insect life and human history. Hope Davis as Margot’s mom counsels her to accept discomfort, enlisting her in a reluctant duet of Cole Porter’s sugar-baby camp classic, “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” — for Margot’s actual stepdad. And winking at the story’s internet saga, the film gets its own online crusader with Margot’s no-nonsense best friend Taylor (Geraldine Viswanathan), who moderates a “Vagenda” subreddit.

The film colors in the story’s brief sketches of Margot’s early acquaintance with Robert (Nicholas Braun, before recent allegations). Emoji-studded text bubbles consume the screen and evaporate as quickly. Roupenian alludes to Margot’s high school boyfriend, who was unsure of his sexuality. In the movie, we see them discuss it, and Jones’ face illuminates Margot’s experience of their past sex life: His lack of enjoyment hurt her. In Robert, she craves someone who might truly desire her.

Judy Blume, James L. Brooks and Kelly Fremon Craig hash out — and argue over — how they finally came to adapt “Are Your There God? It’s Me, Margaret.”

Early in the film, we see Margot walking among blue emergency towers on campus, telling Taylor when she expects to be home. It’s the first in a series of standard safety measures women viewers will recognize — or feel distressed to see Margot forgo, recasting the classic horror cliché (meet in public! tell a friend where you are!). As in the story, when Robert is silent in the car, Margot registers her vulnerable position. The scenes play with genre cues, but Jones makes the gut-check anxiety real.

When it comes to the movie Robert picks for their date, Ashford and Fogel venture a bit of cultural context for Robert’s half of the encounter. Where in the story he chooses a dreary historical drama, here he’s devoted to Harrison Ford, who taught him about romance. “The Empire Strikes Back,” “Blade Runner” and “The Last Crusade” feature seduction scenes in which Ford is presumptuous and pushy; his female co-stars nevertheless swoon. In that sense, the performances share something with Pornhub, where Margot later speculates that Robert gets his more intimate moves.

Disappointed by his sullen attitude and abominable kissing, she does what girls learn to do: She second-guesses herself. Trying to rationalize, Margot imagines Robert confiding in a sage therapist (first-rate Fred Melamed, straight from collective subconscious casting). In the story’s miserable sex scene, she conjures a future boyfriend with whom she can laugh. Here she dialogues with her authentic self, observing from across the room, like Diane Keaton’s spirit during sex in “Annie Hall.” Through the perspective of the ambivalent party, the humor takes on a grim quality.

After the story’s original endpoint, Robert comes lurking outside Margot’s workplace. Feeling threatened, she seeks to protect herself. A frenzied showdown carries the conflict to its furthest extreme, while maintaining Roupenian’s sly technique of constantly opening room for doubt. At the harrowing climax, I found myself applauding Fogel’s deployment of a cable-knit sweater and, yes, a mysterious feline.

Roupenian’s story highlighted how life as a woman can feel like an exhausting game, one we sometimes forget we’re playing. The film makes it just a little more fun, at least for its runtime.

Johnson’s work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, the Believer and elsewhere. She lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.