On the Shelf

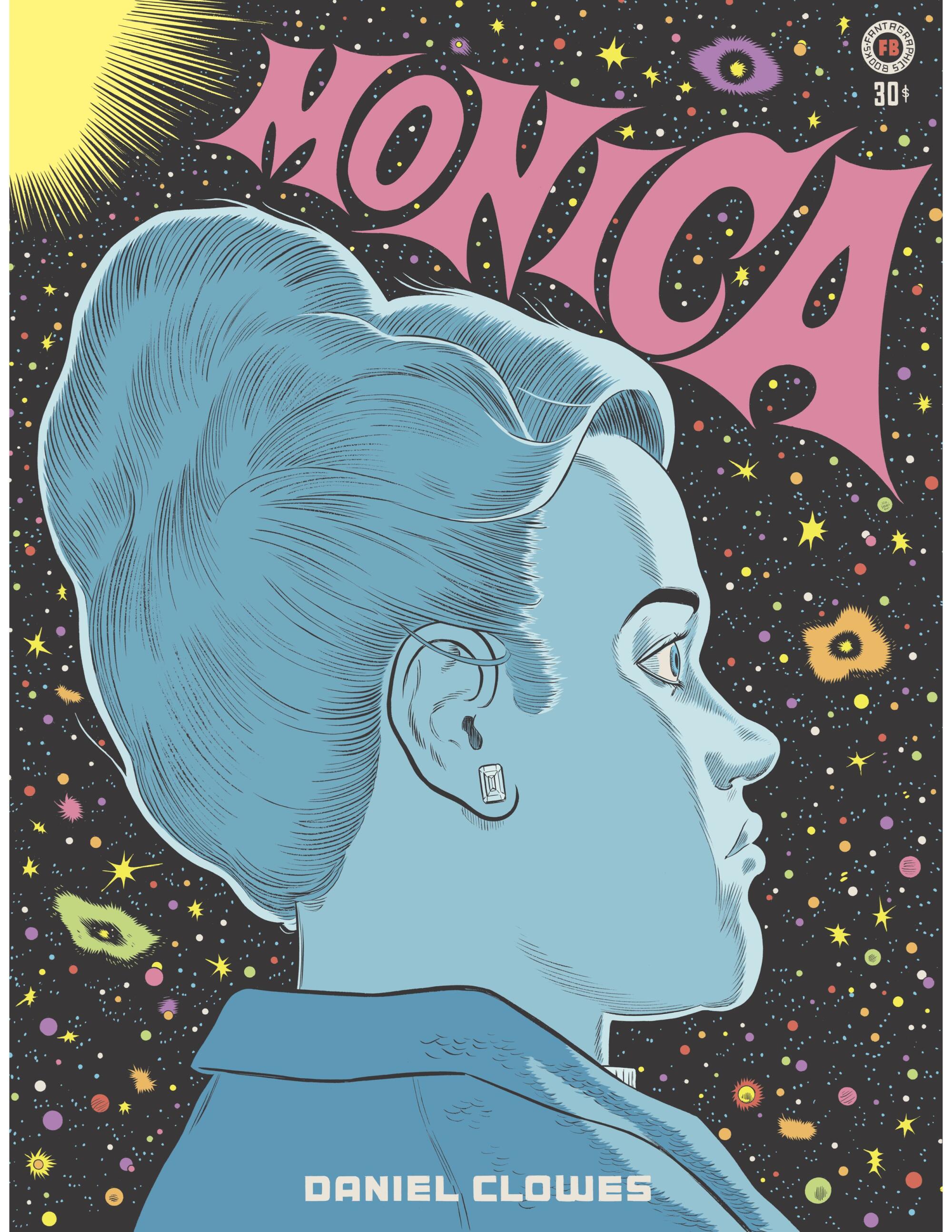

Monica

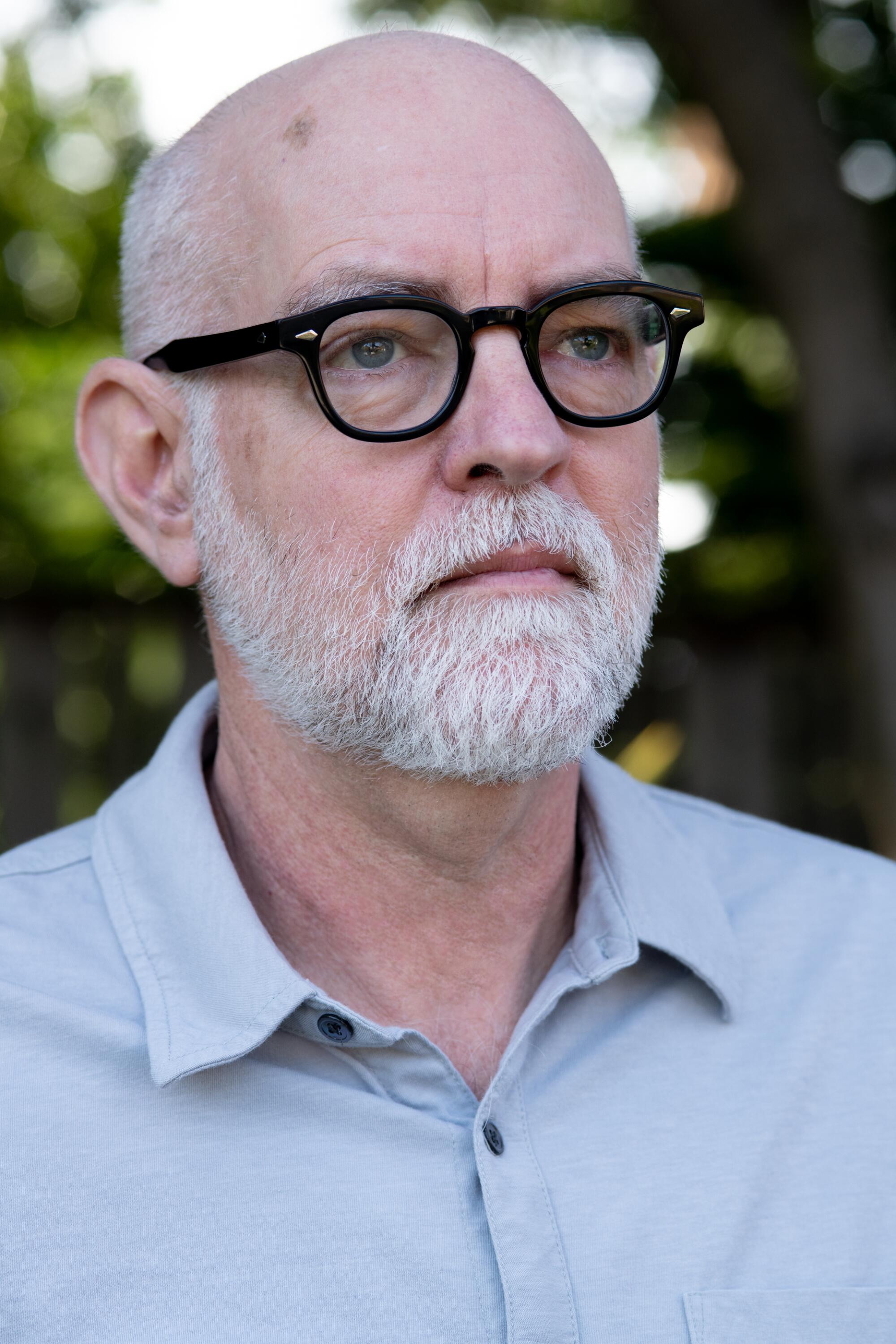

By Daniel Clowes

Fantagraphics: 106 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

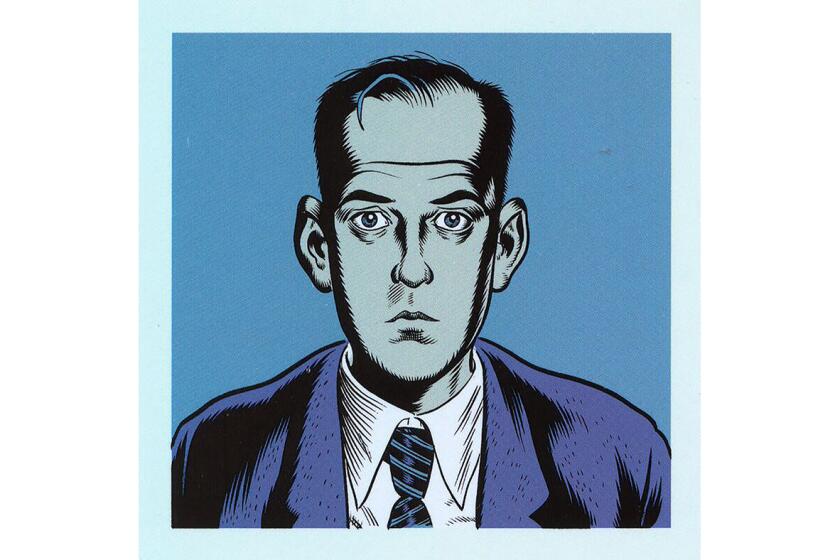

Daniel Clowes has been writing and drawing comics professionally for almost 40 years, turning out some of the most acclaimed and influential graphic novels the medium has produced — including “Ghost World” and “Wilson,” both of which he helped adapt into movies.

Yet even now, the way the 62-year-old works is “mysterious, even to myself.”

“I sort of imagine what a book would look like and then I start moving toward that,” he said in a Zoom interview. “It’s almost like a sculpture more than a comic.”

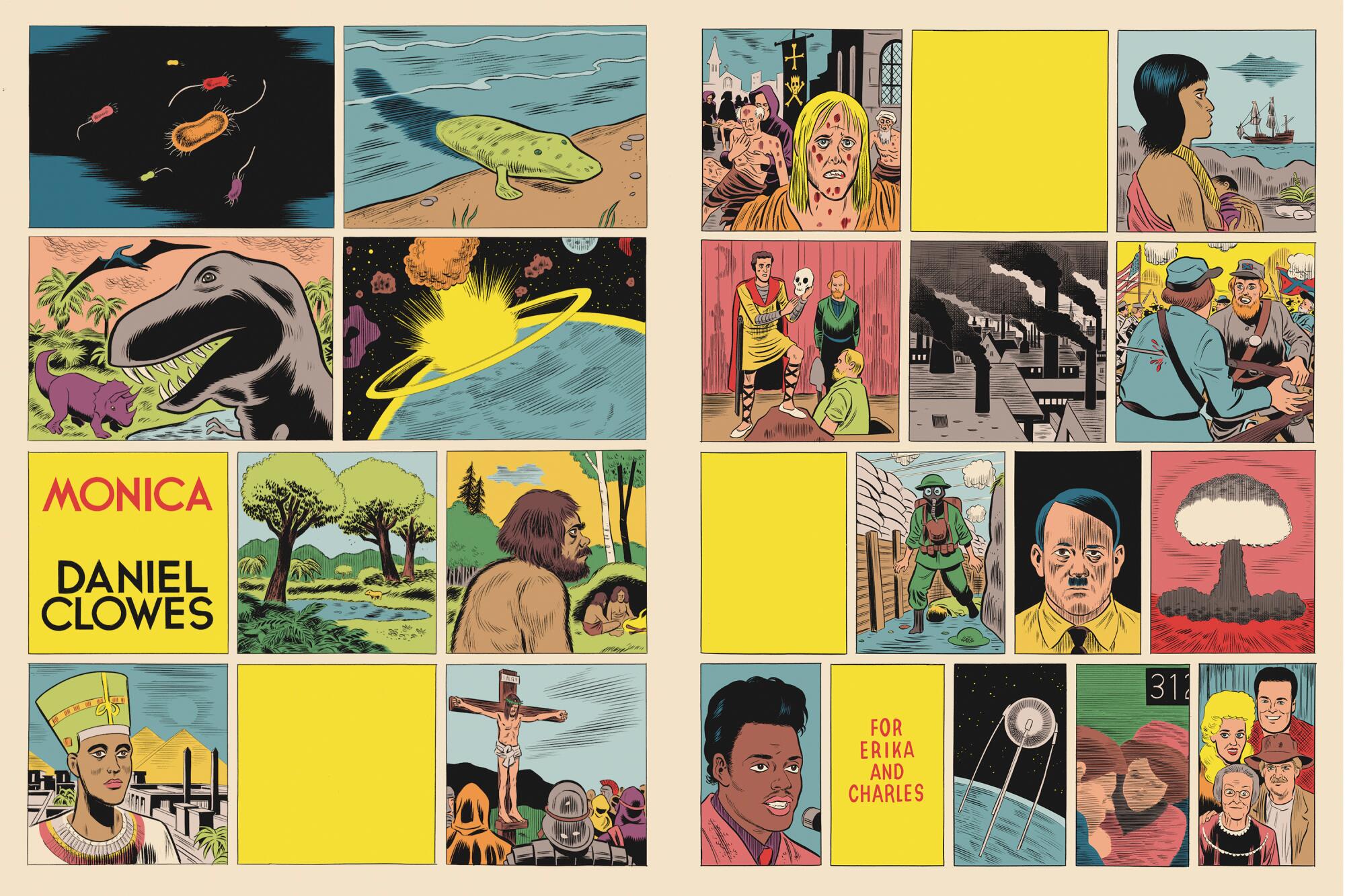

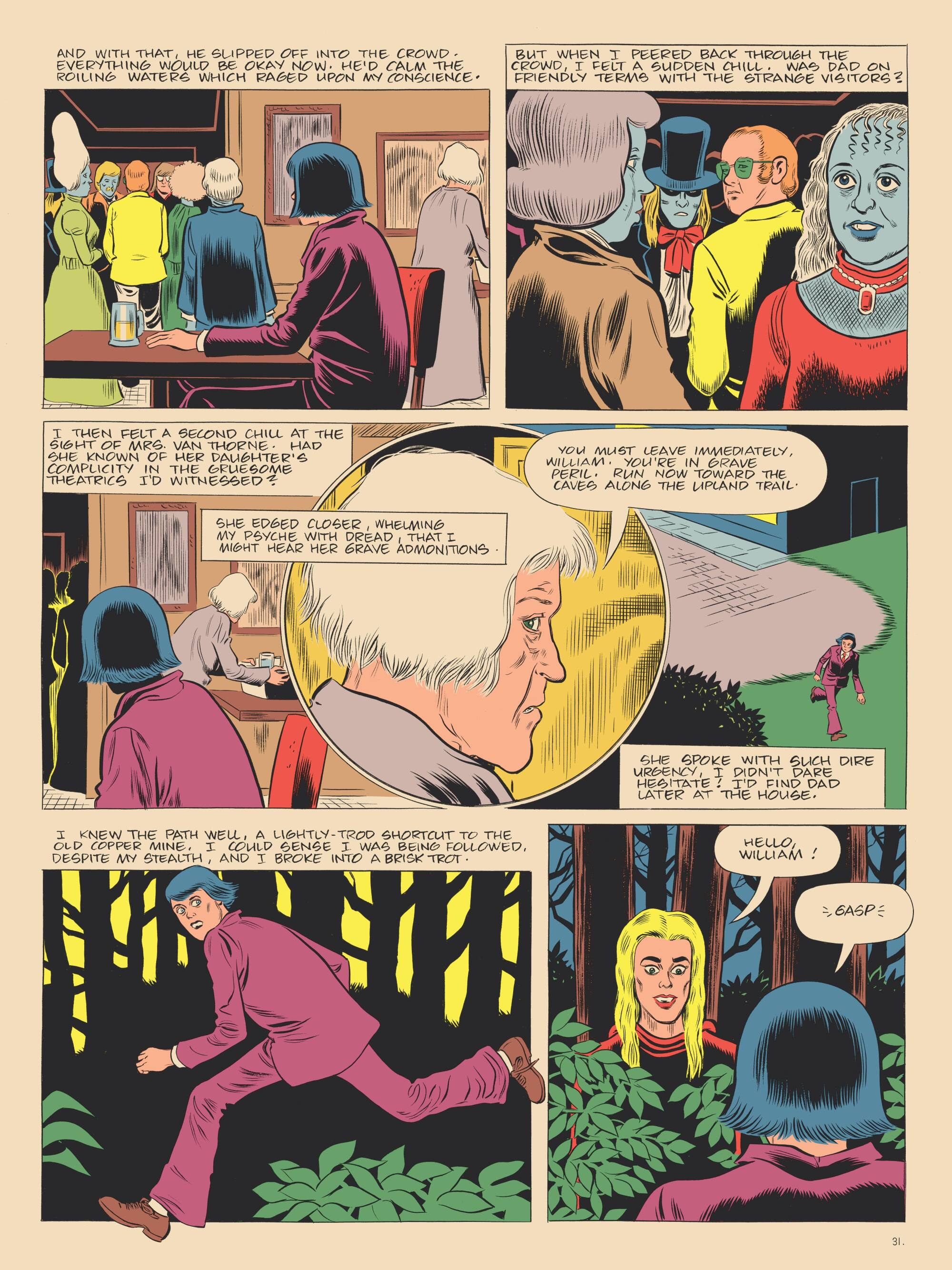

Clowes’ latest book is “Monica,” a collection of nine interconnected stories — and also so much more. Initially, each story recalls a different classic comics genre: a little war, a little romance, a little horror and so on. Gradually the genres bleed into one another until, as Clowes described it, “It’s like when you mix all the colors together and it just turns gray.”

Daniel Clowes is not a man of science.

The result is a work that Clowes’ friend Ari Aster, the writer-director of the films “Hereditary” and “Midsommar,” described via email as “Dan’s magnum opus.”

“It feels like an unselfconscious snarling together of all the phases and styles and preoccupations of his career,” Aster said, “while also being among the most personal things he’s ever written.”

The personal parts are what longtime fans may find the most moving. Clowes’ comics have occasionally veered into first-person essays, and his stories are often laced with his own memories and observations. “Art School Confidential,” which has also been made into a movie, is a fiercely honest and hilarious memoir. But “Monica” cuts deeper.

Clowes began the project by envisioning the kind of cheap old square-bound comics anthology that gathers dust in thrift shops — like a 1970s DC Comics “100-Page Super Spectacular,” but without superheroes. “It was almost like a dream image,” he recalled. “It seemed like something that should exist.”

Originally the book’s nine stories were going to stand alone, but during the writing process Clowes shifted toward telling the story of one person’s life against a backdrop of paranormal suspense: a roman à clef crossed with EC Comics’ “The Haunt of Fear.”

When the first issue of Daniel Clowes’ comic book “Eightball” was published in October 1989, Fantagraphics Books printed 3,000 copies, and Clowes was sure it would take about five years to sell them all.

So while there are tangents throughout “Monica” — an aging artist’s rant in one piece, a sort of detective story in another — Clowes returns repeatedly to the title character. His Monica is a lost soul, who is abandoned by her free-spirited hippie mother as a child and then spends much of her adulthood trying to piece together what exactly happened.

Monica’s story is, in part, Clowes’ story. His early years were also a whirlwind, with multiple moves and different father figures.

“I had a very chaotic childhood and I never understood it,” he said. “I always imagined that after my mom died I would talk to my brother and he’d finally explain the logistics of it all. And then my brother died before my mom, who died about a month later. I have no other relatives. That’s it. There’s nobody left who knows the story.”

Through letters his mother left behind and fragments of his own memories, Clowes has puzzled out a few details. His mother and father were involved in auto racing in Clowes’ hometown of Chicago; they hired a driver for the race car they built together. As Clowes tells it, his mother left his father for the driver — “who I vaguely remember.” But then the driver died.

“Then I was taken to my grandma and that was kind of it,” Clowes said. “It was just this very complicated thing.”

In “Monica,” the character’s quest to understand herself by learning more about her mother takes some more dramatic turns. She discovers a radio that broadcasts her dead grandfather’s voice. She becomes the rich and famous owner of a candle store. And by following her mother’s trail, she ends up living with a dangerous, distrustful cult.

Alex Segura’s “Secret Identity,” about a Latina who invents the Legendary Lynx and moonlights as a PI, is the unlikely culmination of a life spent in love with genres.

To illustrate the sinister, supernatural forces creeping underneath Monica’s life, Clowes drew on images from the comics equivalent of B-movies: long-forgotten imitation EC, DC and Marvel comics cranked out by writers and artists who ended up pouring their own fears and anxieties onto the page while scrambling to make deadline.

“Those stories are mostly unreadable,” Clowes said, “But the individual panels to me had the weight of a great enigmatic painting or movie. Something that had a lasting power.”

The motif of mysticism that runs through “Monica” also recalls the work of Clowes’ cartoonist friend Richard Sala, who died while the book was still being created — and whose fascination with H.P. Lovecraft and pulp mysteries became an inspiration to Clowes.

“I started to imagine Richard as like a ghost haunting the entire book,” Clowes said. “Standing there in the panel, observing.”

The two men lived near each other in Oakland, where Clowes still lives with his wife, Erika. Clowes and Sala used to get together with other local artists to talk about comics, movies, life … everything.

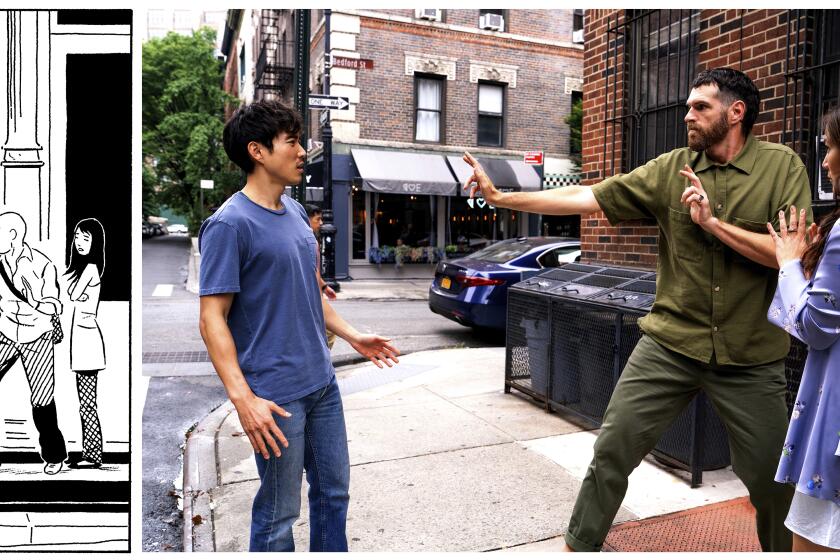

It’s a tradition Clowes has maintained, offering companionship and advice to younger cartoonists including “Shortcomings” author Adrian Tomine and “The Man in the McIntosh Suit” author Rina Ayuyang. “He is still keeping up with what current comic artists are working on and I appreciate that,” Ayuyang said via email. “He’s so down-to-earth and unassuming. Maybe it’s the Midwesterner in him.”

Adrian Tomine adapted his graphic novel ‘Shortcomings’ into a film directed by Randall Park, resulting in an effective, at times transgressive rom-com

Tomine and Ayuyang have both read “Monica,” and they have their own takes.

Tomine, via email, wrote, “It’s got a certain tenderness, especially in relation to childhood, but it’s also infused with a raw sense of grief and mortality that, believe it or not, makes all his earlier work seem sugarcoated.”

Ayuyang’s read is more existential. “At its core, the book is about isolation and a need for belonging,” she said, “but there’s also a desperate search and attempt to connect with the pieces of one’s past, in order to define the meaning of one’s present, to understand how we came to be, on a personal level and on a cosmic level.”

Clowes himself is cagier about how to interpret “Monica” — and in particular its startling ending, which Aster described as a “gut punch.”

“I know after the fact what it all means,” Clowes said, describing an approach to storytelling that has been compared to the noir-ish nightmares of filmmaker David Lynch. “When I’m doing it, it’s like being in a dream. You get in a certain state and follow that path of logic. It has a certain vibration to it, where you’re like, ‘OK, this panel’s right, this panel’s right…’ It’s like a tightrope walk.”

Clowes said making “Monica” was the most purely enjoyable experience he’s had in his career — which may be why it took him more than five years to finish. And it reaffirmed that he’d rather be working on comics than movies. “I’ve got a few little ideas [for films],” he said. “But I’m mostly just all comics. That’s all I want to do. Movies aren’t as much fun.”

Dark teen comedy takes sharp stabs at conventional values.

Aster understands. “I love the films that he and [director Terry] Zwigoff made together,” he said. “But if Dan is only functioning as a screenwriter, he is being held out of a process for which he has a real and rare genius, and that’s in image-making.”

As his younger colleagues attest, Clowes is still studying and refining his craft. “I feel like it took me almost 40 years to get to the point where I can actually understand some of what I was always trying to do,” Clowes said. “I’m at the age where you should be stuck in your thing and riding it until you’re done. Instead, I feel like, ‘Oh man, if I had another 30 years I could really do something great.’”

Murray is a freelance pop culture critic and reporter from Central Arkansas.

Clowes will be signing copies of “Monica” at Skylight Books on Oct. 20.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.