Review

Romney: A Reckoning

By McKay Coppins

Scribner: 416 pages, $33

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

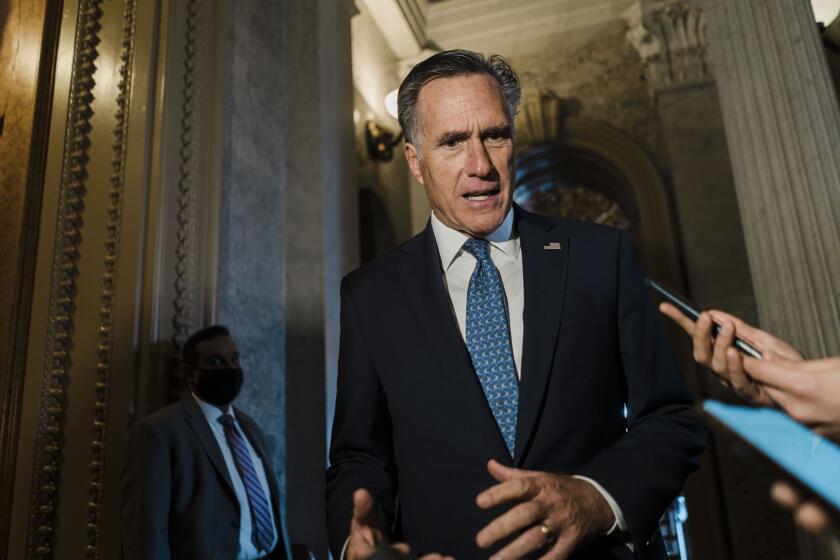

Few political figures have undergone a more abrupt change of stature than Mitt Romney. Republicans’ presidential nominee in 2012, Romney now is an outcast in the party. Once seen as a pragmatist prone to flip-flopping, he’s now taking a bold, career-ending stand against Donald Trump.

That is the journey chronicled in “Romney: A Reckoning” by McKay Coppins, a political writer for the Atlantic, a scoop-rich biography released on the heels of his Senate retirement announcement.

Why do we care about a failed GOP presidential candidate who’s headed off the national stage? The story of his career is an especially clear window onto the forces that over the last decade have transformed the GOP, once a business-friendly bastion of conservatism, into a cauldron of anger, fear-mongering and demagoguery that has no place for Republicans like Romney.

A former advisor to Utah’s buttoned-down senator calls it “Romney unplugged.”

Coppins gained extraordinary access to Romney’s private journals, texts and emails and was granted hours of interviews with Romney over two years. The tell-all details gush forth: When Trump spoke to Senate Republicans privately one time, they burst out laughing after he left. Before the Jan. 6 insurrection, Romney texted Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell about possible violence, and got no response.

Romney said more than a dozen Republicans privately expressed solidarity with his criticism of Trump — including McConnell, who told him, “You are lucky. You can say the things that we all think.” McConnell told Romney during Trump’s first impeachment trial that the House managers had “nailed him,” but he still voted to acquit the president. (McConnell and his staff later told Coppins he did not recall either of those conversations.)

Romney’s assessments of GOP presidential candidates are withering: Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry had a “prima donna, low-IQ personality”; former Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal was a bit of a “twit.” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis on the campaign trail “looks like he’s got a toothache.” Romney even dishes on his colleagues’ languid exercise regimes in the Senate gym.

Many readers will come for the juicy scoops and score-settling, but the book also tries to do something more important: Coppins raises probing questions about how much Republicans like Romney were complicit in the rise of Trump.

“Was the authoritarian element of the GOP a product of President Trump, or had it always been there, just waiting to be activated by a sufficiently shameless demagogue?” Coppins asks. “And what role had the members of the mainstream establishment — people like him, the reasonable Republicans — played in allowing the rot on the right to fester?”

Woodward’s journalism helped bring down Richard Nixon. But “Rage” it too ploddingly neutral and enamored of access to make a dent in this fallen age.

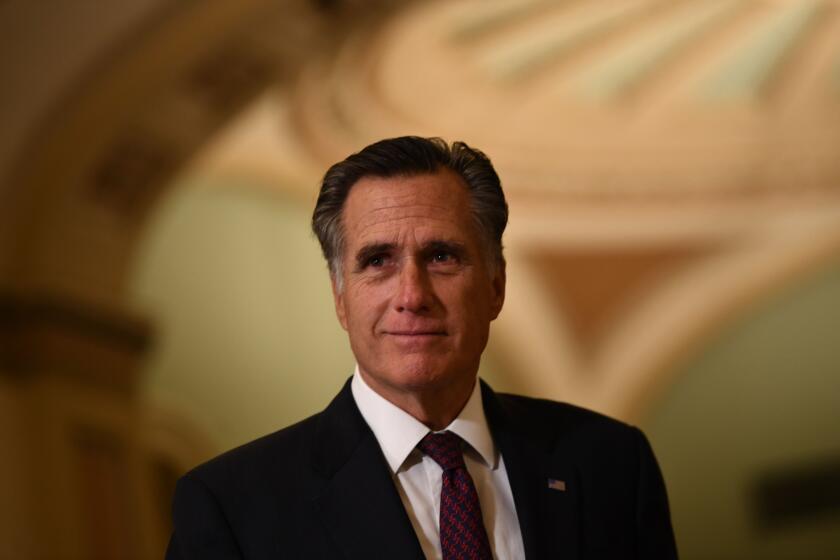

Coppins knows Romney well, having covered his 2012 presidential campaign. And like Romney, he is a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, bringing special insight to his reporting on a campaign where Romney’s religion was an issue.

In his interviews with Coppins, Romney confided early this year that he would not seek reelection in 2024. An advance excerpt of the book ran last month in the Atlantic when Romney made that public.

Romney had saved reams of personal journals, texts and emails to write his own memoir, but decided against it and gave the trove to Coppins. That gives rich texture to Coppins’ review of Romney’s multifaceted career: wealthy management consultant; president of the 2002 Olympics in Utah; governor of Massachusetts; twice-failed presidential candidate; Utah’s U.S. senator; isolated anti-Trump Republican.

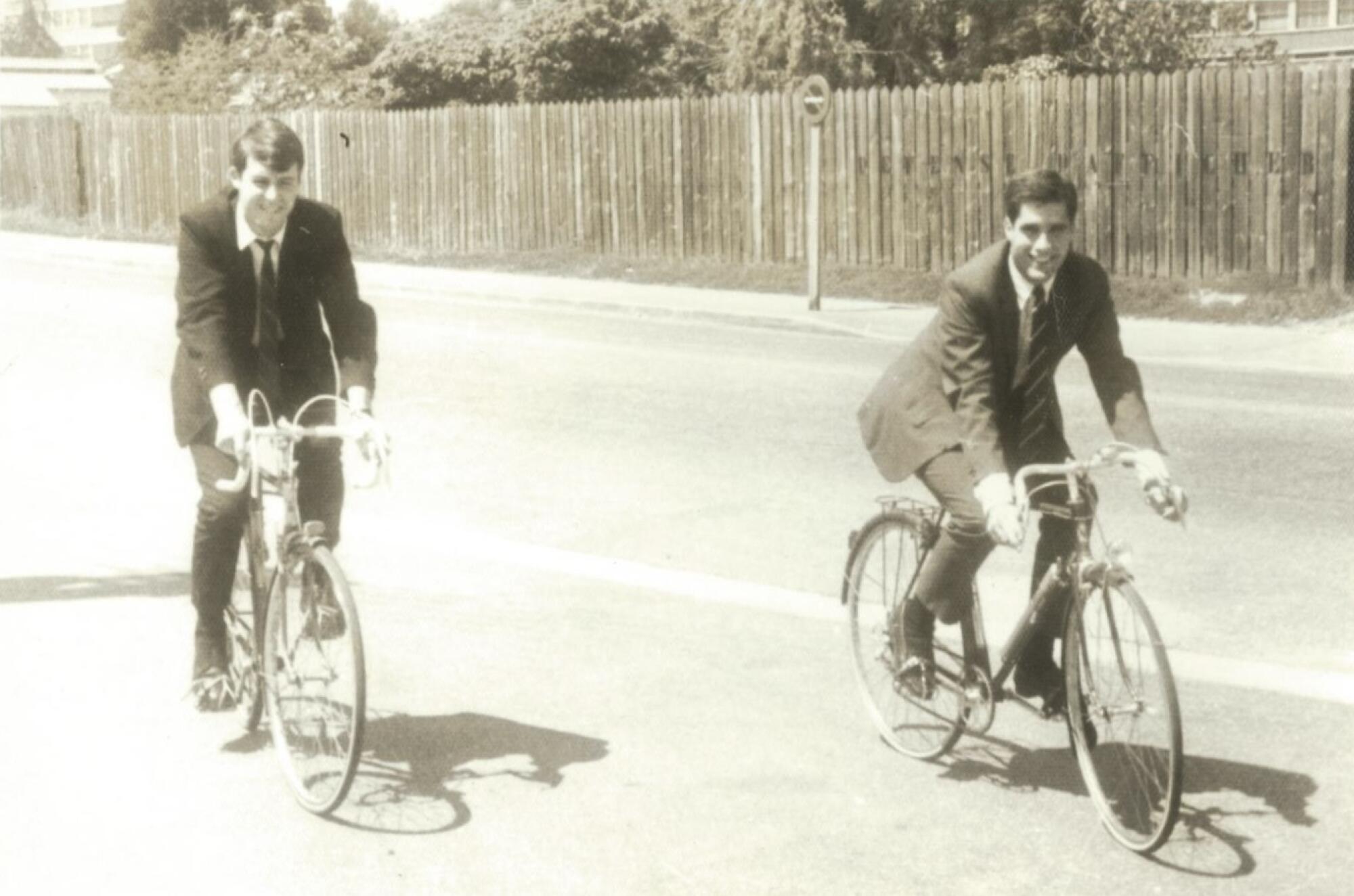

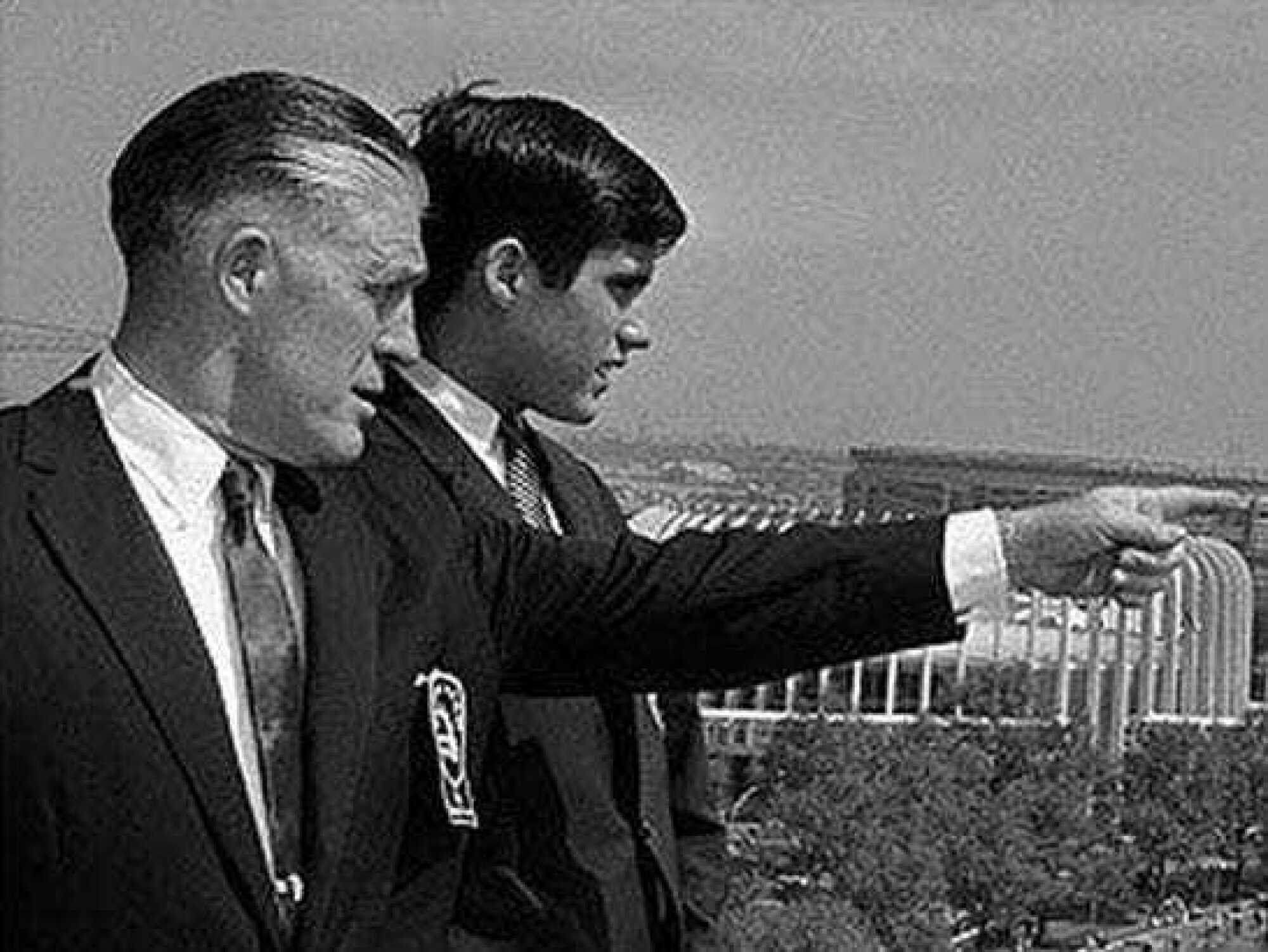

Through it all, one figure looms large: His revered father, George Romney, a successful auto executive, governor of Michigan and failed candidate for president in 1968. To Romney’s mind, the collapse of his father’s campaign came from one poorly worded, offhand statement: Explaining his new opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam, he said he’d been “brainwashed” into supporting the war. He was blasted by critics for using an emotionally charged word that made him look indecisive.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

That haunted Romney when his 2012 campaign was crippled by a leaked tape of him speaking dismissively of 47% of the electorate — voters he said paid no income taxes and lived off government aid who would vote for President Obama “no matter what.”

“The spectre of George’s gaffe-induced meltdown had haunted his son’s entire political career,” Coppins writes. “Somehow it seemed darkly fitting that his own quest for the presidency would end in a similar whimper.”

But deeper factors made Romney a bad candidate, one who didn’t make clear what he believed in. His record was riddled with shifts on issues like abortion and healthcare. A campaign spokesman once compared his evolving political views during the campaign to shaking an Etch-A-Sketch.

Coppins offers this assessment: “Romney was not an ideologue.... He was a believer in fiscal prudence and sober thinking, in well produced white papers and the Wall Street Journal, in spreadsheets and data and running the numbers one more time. He saw himself, proudly, as a partisan of pragmatism.”

Mitt Romney’s vote against President Trump doesn’t change who he is and what he stands for.

But Romney’s spine stiffened in the Trump era, when he emerged as one of the few elected Republicans to openly criticize the 2016 presidential nominee. Later, as a senator, he was the only Republican to vote to convict Trump in his first impeachment trial. Just six Senate Republicans joined him in voting to convict Trump a second time, over his role in the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Romney was disgusted by seeing how driven his colleagues were by their fear of losing office, and how that kept most from denouncing Trump. But it was a lot easier for Romney, a septuagenarian senator with an opulent life awaiting him in retirement, to take the political risk of alienating Trump and his supporters.

McKay Coppins’ “Romney: A Reckoning” boasts full access to Sen. Mitt Romney, but also asks hard questions about his complicity in the rise of Trump. (Jessie Pierce; Scribner)

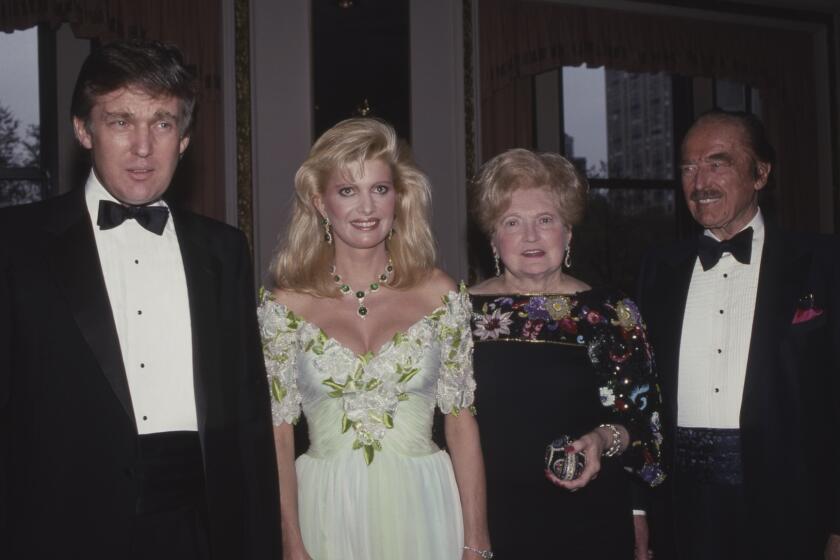

He was not always so bold. In his 2012 campaign, Romney accepted Trump’s endorsement. He even wrote in his journal that he kind of liked the bombastic businessman. “No veneer, the real deal. Got to love him. Makes me laugh and makes me feel good.” Despite denouncing Trump in 2016, Romney entertained being his secretary of State. When he ran for Senate in 2018, he said little about Trump.

“Romney hadn’t yet fully reckoned with his own coddling of Trump and what role he may have played in elevating him,” Coppins wrote. Romney’s comment: “Obviously if I did anything to help legitimize him, I regretted it.”

In announcing his retirement, Romney talked about the need for generational change in politics. As he has become an anachronism in his party, so too has President Biden, whose lifelong faith in bipartisanship also makes him an outlier.

The President’s “only niece,” clinical psychologist Mary Trump, portrays a man warped by his family in “Too Much and Never Enough.”

So it is no surprise that the two men have formed a friendly relationship in recent years. Their casual phone calls begin with “This is Joe.” Romney once advised the president on how to look less old: Don’t shuffle and take longer strides. Biden once called Romney just to say how much he admires him.

As he heads to the exit, Romney told Coppins his advice to politicians is: Care less about how things play out in the short run and more about how history will judge you, what your obituary will say. With his career finale stand against Trump, Romney seems to be trying to rewrite the lead of his own obituary from “failed presidential candidate” to “stand-up guy.” Chances are, his obit will include both.

Hook is a former political reporter for the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.