I wanted to write a book of L.A. noir for decades. But first, I had to live it

On the Shelf

Thirteen Question Method

By David L. Ulin

Outpost 19: 184 pages, $19

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

I decided to write about Los Angeles before I ever moved to Los Angeles. That I didn’t know this at the time makes me want to re-imagine my relationship with the city now as something latent, something protean. Unsurprisingly, it all began and ended with noir, a style of writing Los Angeles more or less invented, going back to Raymond Chandler and the woefully misremembered Paul Cain. I had become a deep reader of the genre in my 20s, and, as all writers are readers in emulation, I began to think about writing a hard-boiled fiction of my own. The appeal of that sort of book, then as now, felt palpable: an “axe for the frozen sea within us,” to borrow Franz Kafka’s term.

I wanted to write a novel that operated without pity or forgiveness. I wanted to write a novel that left its characters and its readers no way out. I wanted to write a novel that used the parameters of noir to reflect on the isolation of living. That novel, 30-some years later, would become “Thirteen Question Method,” an existential thriller, set in Hollywood, in the vein of noirists such as David Goodis or Charles Willeford — written to be short, sharp, shocking; trafficking in neither hope nor redemption; as bleak and pointed as a stiletto’s blade.

The 13 most essential L.A. crime books — from Chandler, Hughes, Mosley and Ellroy to Steph Cha and Ivy Pochoda, with some ‘Helter Skelter’ in between.

The problem at first was that I hadn’t lived it, or maybe it was that I didn’t know the city yet. I had a conceit, but I didn’t yet have a narrative. The territory I meant to investigate was not crime so much — or exclusively — as what I’ve come to call the antisocial novel, the literature of the miscreants and malcontents. I think of Joris-Karl Huysmans’ “Against Nature,” Russell Greenan’s “It Happened in Boston?” and James Hogg’s “The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner,” not to mention the work of Kafka himself. Throw in Jean Genet, Albert Camus, Alexander Trocchi and William S. Burroughs.

Much of this material was hard-boiled in its fashion; Camus acknowledged the influence of James M. Cain. But what I was after was a more direct through line linking the literature of alienation with that of noir.

This required a leap of the imagination. I had been raised in the tradition of so-called serious fiction, taking to heart Graham Greene’s dualistic breakdown of his own work into “novels” and “entertainments.” Yet as I devoured title after title by the Cains and Dorothy B. Hughes and Jim Thompson, Georges Simenon and Leigh Brackett, I began to suspect that Greene had been wrong. Then, in 1991, I moved to Los Angeles, where no one seemed to care very much about imposing spurious hierarchies on creativity.

As Chandler insisted in his 1944 essay “The Simple Art of Murder”: “There are no vital and significant forms of art; there is only art, and precious little of that.”

Do I need to say that this transformed me, as much as Kafka’s ax? Art was in the doing, in the making. Noir helps to make the point. In Simenon’s “Red Lights,” a middle-class marriage unravels as a couple makes a Labor Day drive to pick up their kids at summer camp, while Goodis’ “The Blonde on the Street Corner” focuses on a down-and-outer who loses “all hoping for a cleaner better life.” If these are not Southern California novels, they share something of its sensibility. The universe they evoke is indifferent, if not actively malevolent. It’s an idea that resonated all the more for me as I began to engage more deeply with Los Angeles: its dreams and its disruptions, its Edenic fantasies and often harsh realities.

Joan Didion’s ‘Play It as It Lays’ is the third most popular L.A. book among writers surveyed by The Times. David L. Ulin explains why her fiction matters.

I don’t want to make the process sound too conscious. I had the title of “Thirteen Question Method,” a key to the novel that also riffed on Chuck Berry, when I arrived in California — but not much else. There was a loose setup: a narrator caught up in someone else’s inheritance dispute.

Noir as a genre relies less on plotting than on its own internal logic, the logic of despair. But it does require a perspective, as well as a particular idea of place. Los Angeles bestowed that, rendering Chandler’s ideas three-dimensional and whole. No vital and significant forms of art? This meant the only thing that mattered was the execution. Or, better yet: the will. Los Angeles was the embodiment of this intention. Often dismissed with the language of a fever dream — La La Land, lotus eaters, blah blah blah — the landscape I encountered, prone to burning and to quaking, existed instead in a constant state of emergence.

I’m not referring to the myth of reinvention so much as a kind of necessary blurring, in precisely the way Chandler meant. The flattening of time, the speed with which the city expanded, led to a collective fascination with modernity. Hollywood was a big part of this — despite, or perhaps because of, the awful way it treated writers. To write prose here was to experience the literature of alienation firsthand.

And yet, it was also to experience a kind of freedom from literary elitism, to turn one’s back upon the East. Nathanael West shed the high modernism of “Miss Lonelyhearts” for the more cinematic bleakness of “The Day of the Locust.” James M. Cain’s “Mildred Pierce,” published in 1941, is both a three-act melodrama and possibly the finest novel ever written about this place. Such books were not afraid to rely on convention … or to overturn it when it served their ends. Such books existed, at the same time, in and out of genre. They took what they needed from a variety of forms. The idea was that those Eastern hierarchies didn’t matter; they never had.

As I began to map out the parameters of “Thirteen Question Method” — the bungalow court and the sullen streets of Hollywood, the rich folk who lived high in the hills and the unreliable narrator stewing in his disassociation — I came across a lot of other models: Octavia E. Butler, who found in genre something of a literary liberation; John Fante, whose “Ask the Dust” is as noirish a nongenre novel as I know. These works take place in the existential city, where the monotony of daily life can be disrupted in an instant, any time a fault slips or a spark smolders in the depths of a canyon and explodes into a conflagration: “The city on fire,” Joan Didion warns us, “just as we had always known it would be in the end.”

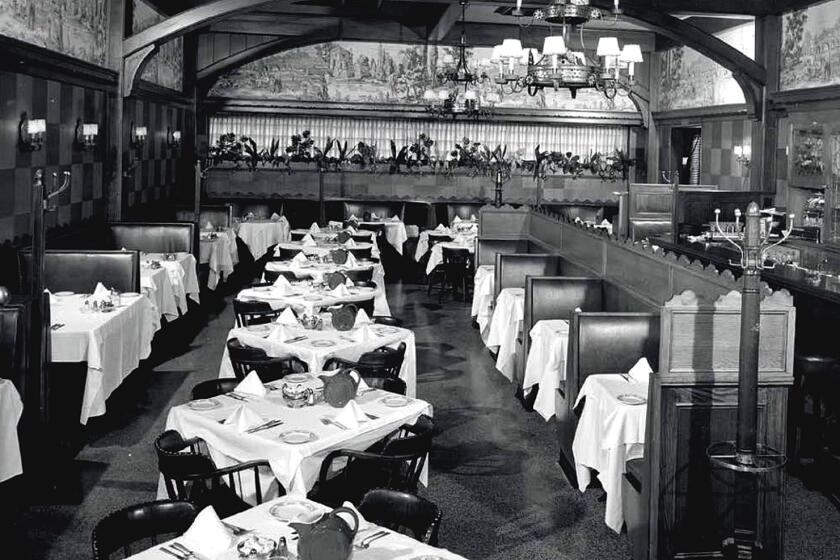

L.A. transplant Stanley Rose’s short-lived 1930s bookstore and boozy backroom became a literary haven for Chandler, Fante, Faulkner, West and many more.

As it happens, “Thirteen Question Method” involves a wildfire. As with so many things in the novel, I did not know this would happen until I got to it. I had to become comfortable with the vernacular, with the idea that people come or stay for a range of reasons, including to hide out from themselves. In an aspirational city, what happens when you don’t get what you want? What happens when you make bad choices, when you allow the chaos to take hold?

These are the questions at the heart of noir, of every literature of alienation. I wanted to write about a character whose desire was to disappear. Not because I don’t understand those urges, but because I do. Like all of us, I am making it up as I go along, trying to keep my hand on the guardrails, doing what I have to do to make it through the day. Noir is what happens when your hand slips, when you go down.

For every one of us in fact or in fiction, this will happen at some point, which is both the challenge and the consolation of the form.

Ulin is a former books editor and book critic at The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.