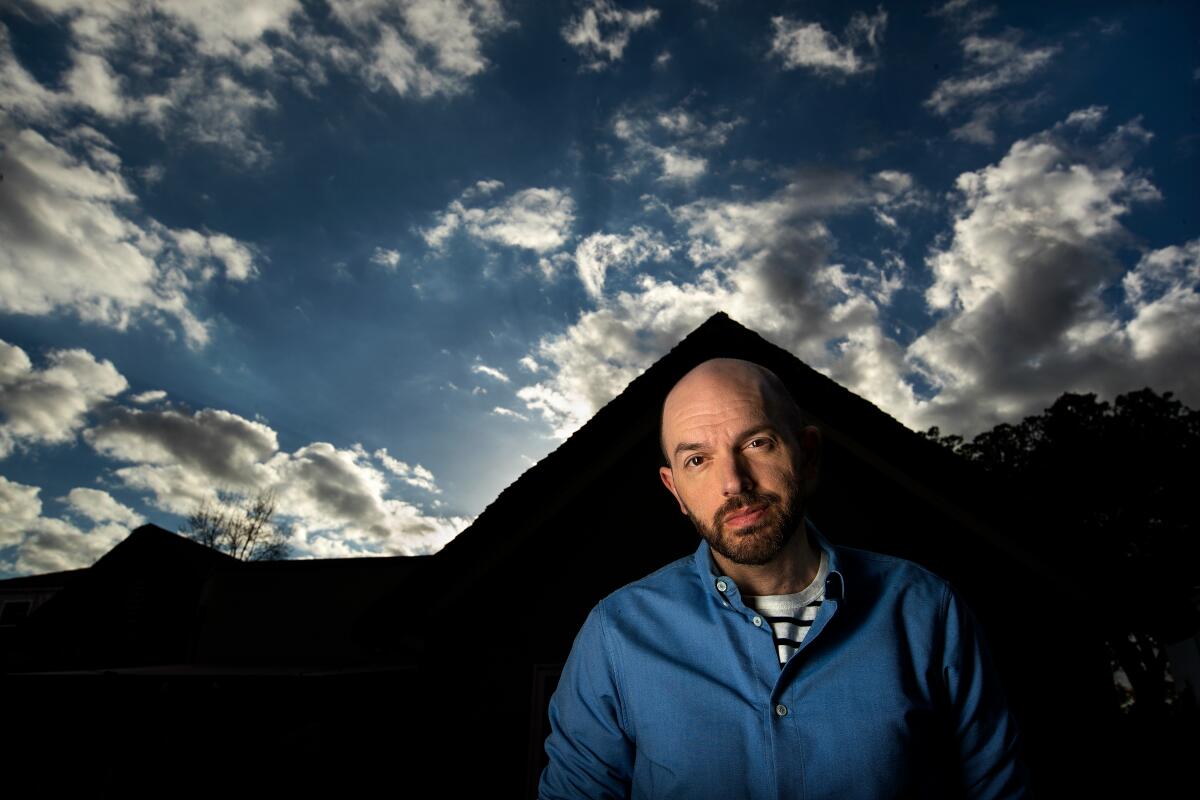

Paul Scheer was abused as a child. His new memoir helped him reclaim ‘the power of my voice for my childhood’

On the Shelf

Joyful Recollections of Trauma

By Paul Scheer

HarperOne: 256 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Paul Scheer knew he had a lot of funny childhood stories — the comedian (“The League,” “Black Monday”) had been regaling audiences with them for years on the podcast “How Did This Get Made?” with his wife, June Diane Raphael, and friend Jason Mantzoukas. But as a memoir reader, he understood that a collection of amusing anecdotes did not make a book.

To create something worth reading, he’d “have to go deeper and tell the stories I’ve never really told,” Scheer, 48, said in a recent video interview from his Los Angeles home. Those stories centered largely around the abuse he (and his mother) suffered at the hands of his stepfather and the fear and shame it caused, especially when his mom and dad didn’t step in to save him. Still, Scheer was adamant that his book not be therapy. “I’ve read books that almost feel too private. I didn’t want that — I’d done that work before I started writing.”

“Joyful Recollections of Trauma,” Scheer’s memoir-in-essays, blends the horrifying and the self-deprecatingly funny, often within the same chapter, sometimes within the same sentence. “Writing this was a process of refining and discovering what the book wanted to be,” Scheer said.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did writing the book change your understanding of your past and of yourself?

These are all things that I knew about myself, but wrestling with details gave me a good point of view and actually helped me bring certain things into therapy. I’m not surprised at the stories, obviously, but I am surprised that some of the connections I didn’t see until they were down on the page. There were things I’d taken for granted and never really examined. As a kid, you don’t know any different — I grew up in this situation that was violent and scary, but it was my life so it was also so normal.

The thing I was most surprised at was the anger that I felt at my parents. I love my parents and have a great relationship with them and they’ve supported me in countless ways, but I had made excuses for them or just said, “It’s fine.” But as a parent myself, in telling those stories, I thought, “If I was in their shoes, I would do something.” So this book made me look at things differently. I think it gave me a better relationship with my kids. I think it also gave me a better relationship with my parents.

It is not a surprise to find that Paul Scheer talks fast. He doesn’t have time not to.

Did you temper what you wrote about your parents and how you felt?

It was something I wrestled with. I don’t think the anger at my parents comes out in the book. I just laid things out without trying to sweeten the edges or making excuses, but this is not a book that I was writing to settle the score. I have a good relationship with my parents. My parents’ friends will read this book, and I wanted to protect my parents from getting slings and arrows from their friends.

Was writing about your stepfather and the abuse cathartic?

I don’t think it was cathartic because I had dealt with it all in therapy and I wasn’t going through that as I was writing it. What it was for me was a release of a burden, a chance for me to tell this story and feel like I had full control of it. What I reclaimed was the power of my voice for my childhood — I’ve been free of those moments already, but now it’s something I don’t have to hide, I can talk about this. Oh, maybe that is cathartic.

Was it difficult to find the right tonal balance?

I thought about it like a conversation. I’m going to tell you these stories. I’m not going to undercut the dark parts, but I also am going to be aware of the valves. No one’s life is just one thing — there are highs and lows and fun. My childhood had these very traumatic moments, but they weren’t the only things that defined me, so the funny stories are in here.

I always kept the abuse stories on the side. But I would tell other stories that I look back on as fond memories, and I’d see Jason’s and June’s faces and they were shocked. And I’d say, “This is funny” and they’d say, “That is traumatic.”

When I’m telling one of those stories and I see someone tense up worrying how to react, I’d inevitably pull back and veer off. Writing the book I could give the push and the pull and guide the story, driving through the parts I want to tell while finding a balance.

SAG-AFTRA approved side agreements allowing more than 100 independent film projects and series to move forward amid the strike, but the deals have spurred debate.

Did moving from New York to Los Angeles help you grow or find yourself?

Moving to L.A. changed my outlook on so many things. It’s the self-help capital of the United States and people here do wild things. There’s a culture where people are fine talking about their issues and there’s a lack of judgment. Los Angeles is open to everything: scream therapy or this or that. They say, “My healer does this” or “I’ve done this ceremony” or “My myofascial release took out trauma.” I have a friend who went to Peru and did ayahuasca and changed his life, but I also have friends who do ayahuasca in an afternoon around somebody’s pool and I say, “You’re just doing drugs.”

So L.A. has freed me of a certain amount of self-judgment.

You started in improv and write about your Upright Citizens Brigade days. How did improv shape you as a person?

Improv to me is truly life. It’s about collaboration. And to me, as a human being, every relationship is about collaboration. To be a good improviser, you have to listen and react, taking cues from other people and giving your partner equal weight. Because it’s all about communication, it forces you to be a kinder human being.

The biggest thing in improv is trust. I was a person who had trust issues, and improv to me was a continual trust fall. In a scene I’m making a choice and I’m going to believe that someone is going to support me and catch me. For a long time in my life, I didn’t have that person to catch me. I always protected myself so I wouldn’t fall. Improv opened me up to believe I can surround myself with good people and then I can do anything with them. Those tenets really have changed my life, and that’s something else I didn’t fully realize until writing the book.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.