CBS’ purchase nine years ago of a small TV station on New York’s Long Island was unusual: The broadcasting giant hadn’t acquired a TV station in years — in fact, it had been trimming its station portfolio.

WLNY-TV (Channel 55) was hardly a powerhouse. It ran old movies, game shows and a half-hour local newscast produced on a shoestring. But the $55-million deal, announced in December 2011, had a prominent backer: CBS Television Stations President Peter Dunn. He promised to boost the station’s stature by deploying “people and resources to fuel a significant expansion of local news programming.”

Today, Long Island-based newscasts are long gone from the station’s lineup, and so are more than 70 people who once worked there. WLNY now airs a parade of courtroom shows, “Pawn Stars,” old CBS sitcoms and a nightly roundup of news from New York, Connecticut and New Jersey.

But for Dunn, the WLNY purchase brought life-changing benefits.

As part of the deal, the station’s founder, Michael Pascucci, threw in a membership to the exclusive Sebonack Golf Club, which he had built in Southampton, N.Y. The private, 300-acre, bay-front retreat draws an ultra-rich crowd — initiation fees top $1 million, according to Golf Digest.

A Times review of court filings, CBS’ internal communications and interviews with two dozen current and former CBS television station employees found that many were troubled by the outcome of the investigation and questioned the company’s commitment to cleaning up its culture.

Dunn treated the Sebonack membership as a personal perk, according to a complaint filed with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission by the former manager of CBS’ TV station in Philadelphia, as well as two other individuals who were aware of the arrangement but not authorized to comment. The deal allowed Dunn to hobnob with billionaires, boost his own social standing and entertain other high-level CBS executives and corporate clients.

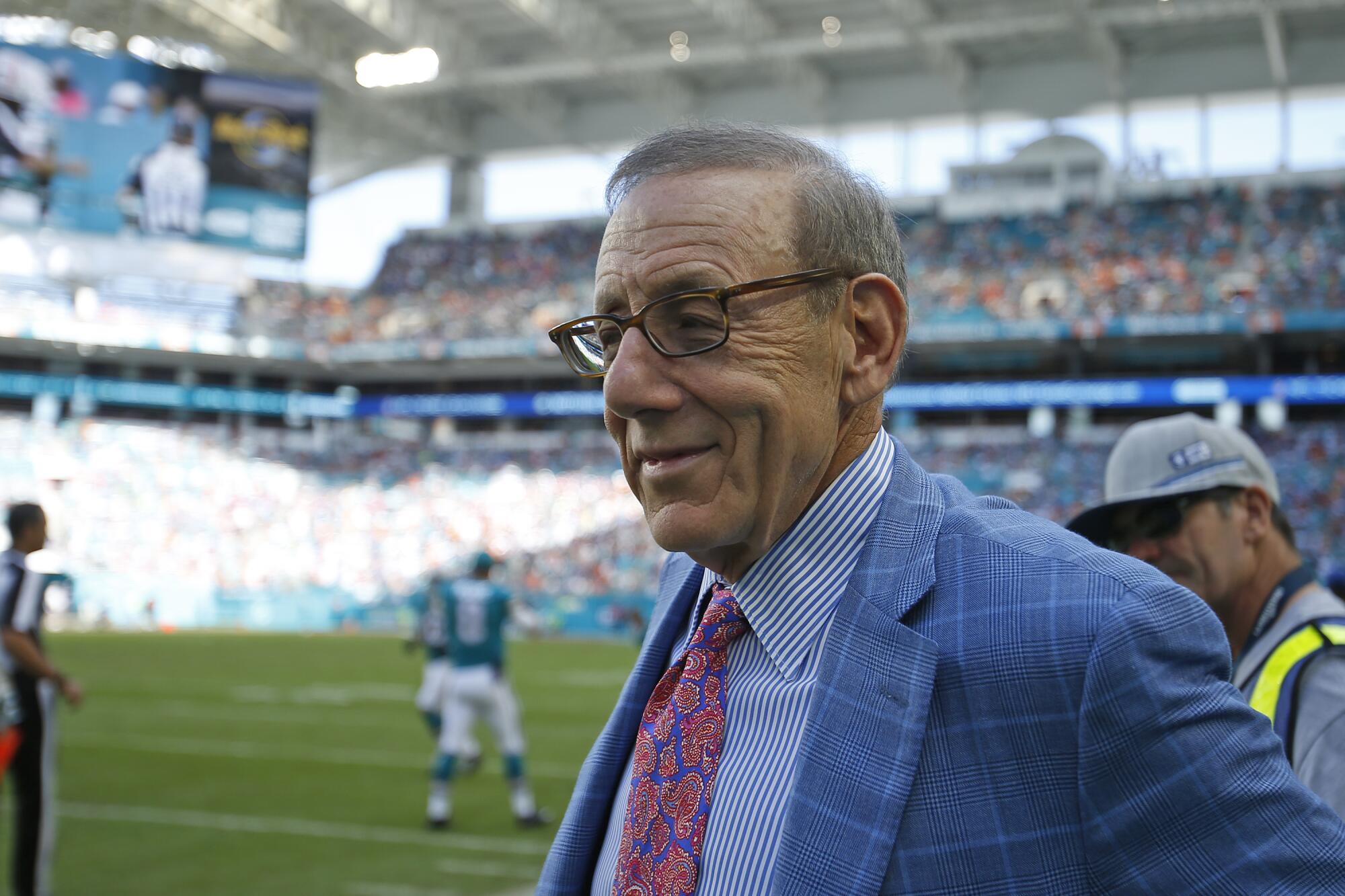

On the night of his 2017 wedding to the sister-in-law of another Sebonack member, billionaire NFL owner Stephen Ross, the families celebrated at the club.

Just last month, Dunn and another high-level CBS executive joked about the station purchase during a Zoom call. “You mention [W]LNY, I usually call that the acquisition of our golf membership ... I mean TV station,” quipped Bryon Rubin, chief operating officer of the CBS Entertainment Group, according to an audio recording shared with the Los Angeles Times. Dunn chimed in: “That’s paid for itself, and then some.”

WLNY’s revenue has shrunk significantly in the years since the acquisition. The arrangement alarmed several CBS executives, who questioned whether Dunn’s acceptance of such a lucrative perk violated the company’s ethics guidelines, which forbid executives from receiving expensive gifts or allowing self-interest to influence company decisions. The matter was flagged for two high-profile law firms investigating alleged misconduct at CBS in late 2018, according to two people familiar with the investigation who declined to comment for fear of reprisal.

A statement by the CBS Board of Directors on the company’s investigation into former Chairman Les Moonves.

In a statement, CBS called the Long Island station purchase a “strategic acquisition” that created value by giving the broadcaster two stations in New York, the nation’s largest media market.

“As part of the acquisition ten years ago, CBS was offered a membership to Long Island’s Sebonack Golf Club,” CBS said in the statement. “The membership was disclosed in advance to senior management and legal counsel. While listed in one executive’s name, this is a CBS membership used to host clients and business partners. Annual dues are paid by CBS and any personal expenses incurred by executives are paid from their own pocket.”

Still, one ethics expert questioned the arrangement.

“From a business ethics perspective, this is an incredible gray area,” said Joanne H. Gavin, associate dean of Marist College’s School of Management in New York. “Nothing about this feels transparent or fair to other CBS employees.”

Dunn declined to comment for this story.

WLNY once had a scrappy staff and an upbeat motto: “We Love New York.” Paula Rizzo, a media consultant, started her career as an assistant producer in WLNY’s newsroom from 2001 to 2003. She said the station had the quirky feel of “The Office.”

There wasn’t a “live truck” capable of transmitting news reports from the field, Rizzo said. Instead, a handful of journalists would spend the day chasing stories, then dash back to the Long Island studios in Melville, where the news director, who doubled as the anchor, would deliver the 11 p.m. news. Traffic reports came not from a roving helicopter but from state transportation department cameras installed along the Long Island Expressway.

“It was an endearing place, with a nurturing atmosphere,” Rizzo said. “You felt like you were part of a big family.”

The patriarch was Pascucci, a car-leasing mogul. In the late 1970s, Pascucci, the son of an Italian immigrant, helped the Roman Catholic diocese of Long Island establish a cable TV channel. He has said he was struck that Long Island, with more than 3 million residents, lacked a broadcast station. “So I built WLNY from scratch,” he told Business Jet Traveler in 2007.

Pascucci declined to comment for this story.

When the station launched in April 1985, Pascucci told viewers it would offer “some local community programming, some morally uplifting programming and a nightly Long Island newscast.”

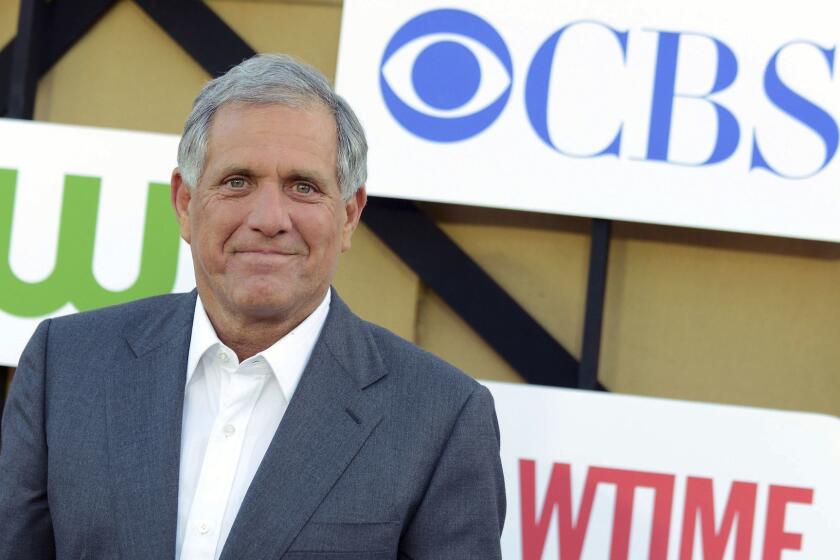

Leslie Moonves was a television great.

WLNY initially aired old Hollywood fare such as “The Doris Day Show,” “The Fugitive” and “Lost in Space.” The station later exploited a loophole to license popular syndicated shows including “Jeopardy!,” “Wheel of Fortune” and “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

It ran the same premium shows as a leading New York City station, even though syndicators typically grant geographic exclusivity — 50 miles — to stations that purchase their programs. Melville is only about 30 miles from Midtown Manhattan, but it skirted the geographic provision because its transmission tower is in Riverhead, on the eastern end of Long Island, more than two hours from New York City.

WLNY generated as much as $25 million a year in revenue before its sale to CBS, said Jerry Diorio, the station’s former operations manager.

“It was a cash cow for years,” Diorio said. “We ran it lean and mean.”

In 1997, Pascucci sold his car leasing company, Oxford Resources Corp., to Barnett Bank (later absorbed by Bank of America) for $570 million. WLNY got a budget boost, used to upgrade equipment, build a new set and nearly double the size of the newsroom staff to almost 30 people, according to former executives.

The Oxford Resources sale also paved the way for a new venture. In 2001, Pascucci bought 300 acres along New York’s Great Peconic Bay after Donald Trump walked away from a deal for the swath of land. Pascucci hired his Florida neighbor, Jack Nicklaus, and noted architect Tom Doak to design the rolling fairways of a par-72 golf course.

In 2006, Pascucci opened Sebonack Golf Club. Membership to his private club was by invitation, drawing from the multimillionaires and billionaires with homes in the Hamptons. Members can stay in one of Sebonack’s four-bedroom, 3,000-square-foot cottages or dine with the upper crust in the stately bluff-top clubhouse.

“It’s like heaven on Earth,” said Elliot Simmons, who has been advertising sales manager at WLNY for more than two decades and once played the course.

It’s not clear when Pascucci and Dunn became acquainted, although a CBS insider said the two met at a TV industry conference.

A fellow Long Islander, Dunn worked in advertising sales at ABC and NBC in New York before joining CBS in 2002 as general manager of its Philadelphia station. In 2005, he was put in charge of CBS’ flagship station in New York, WCBS-TV (Channel 2).

There, Dunn gained a reputation for a relentless focus on the bottom line, said current and former CBS colleagues.

Dunn was elevated to president of the entire chain of CBS-owned TV stations in 2009, and he centralized the business, ensuring that major decisions were made in New York. Dunn has long been a key member of CBS’ senior team, popular among other high-level executives as well as outside business partners, according to those who know him.

Within two years of securing the big job, Dunn was eager to expand in New York by buying WLNY, even though other CBS executives had been lobbying to buy more lucrative stations, three former CBS executives said. These people said they suggested acquiring stations in Washington, D.C.; NFL markets such as the Kansas City, Mo., area or Cleveland; or political battleground states that bring in big money from advertising during election years.

There were valid reasons for the WLNY purchase, and CBS has defended the deal.

More than a decade ago, CBS had just one station in New York, and the company was interested in duopolies — TV lingo for owning two stations in a single market. Such arrangements enable companies to reduce overhead and maximize revenue and profits because one team runs two stations, as is the case with KCBS-TV (Channel 2) and KCAL-TV (Channel 9) in Los Angeles. The company also can spread the cost of syndicated programming over multiple stations.

But prior to WLNY, CBS hadn’t bought TV stations since the 2004 purchase of KOVR-TV in Sacramento and the 2002 deal for KCAL.

While CBS was looking to expand, Pascucci had reasons to sell.

The Federal Communications Commission had mandated that TV stations convert to digital from analog broadcasts — a multimillion-dollar upgrade that would stretch the finances of a small player like WLNY. Also, the industry was poised for consolidation, pressuring independent stations. And Pascucci had a hungry buyer in CBS.

Still, CBS’ interest came as a surprise to WLNY employees.

“There was a collective gulp when they announced the deal,” Simmons said.

Diorio, Simmons and others noted what they saw as a Pascucci touch: WLNY was Channel 55, and it sold for $55 million.

Justin Nielson, senior research analyst with S&P Global Market Intelligence, said the price was reasonable because of WLNY’s proximity to New York, but the station has not been a big money maker. By contrast, he cited Meruelo Media’s 2011 acquisition of independent KWHY-TV (Channel 22) in L.A. for $40 million; since then, Meruelo has made at least $120 million on its investment by selling some of the station’s electromagnetic spectrum. CBS didn’t participate in the FCC spectrum auction, he said.

“[WLNY] was not a big revenue driver,” Nielson said. “And CBS already had a major station in the market.”

According to CBS financial documents viewed by The Times, WLNY generated about $16 million in ad sales for 2020, substantially below pre-CBS levels, in an increasingly challenging local ad market. It’s unclear whether the station is profitable. CBS declined to discuss financial details.

Another incentive for the deal surfaced in a complaint that Brien Kennedy, a former Philadelphia station manager, filed with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission.

In his Jan. 10, 2020, complaint, which was reviewed by The Times, Kennedy alleged a “quid pro quo exchange” in which Dunn and another executive “received two ultra-exclusive club memberships to Sebonack Golf Club in the Hamptons in exchange for purchasing the WLNY television station in December, 2011, in violation of company policy.”

CBS disputed there was any “quid pro quo exchange” and said it accepted just one membership, which was put in Dunn’s name.

Kennedy, who was ousted by Dunn in July 2019, has challenged his dismissal.

For nearly a decade, Kennedy was Dunn’s loyal lieutenant. Both were hard-charging sales guys who scaled the ladder to run valuable pieces of CBS’ vast empire. Kennedy said his relationship with Dunn unraveled in 2019, following an investigation into alleged wrongdoing at CBS. Kennedy contends that he was fired in retaliation for cooperating with an internal review of Dunn’s alleged conduct.

“CBS Television Stations has filed a response to the Commission that disputes Mr. Kennedy’s claim of retaliation and establishes that he was fired for performance,” CBS said in a statement.

Kennedy said he has a vivid recollection of learning about Dunn’s association with the Long Island golf club. In December 2015, CBS station managers were in Dallas for a corporate retreat. Kennedy recalls standing with Dunn in the lobby of the Four Seasons Resort and Club when Dunn said he was waiting to see his “friend Stephen.”

Dunn was referring to Ross, the owner of the Miami Dolphins; NFL owners were in Dallas for a meeting and were staying at the same resort. Kennedy said he was surprised that Dunn had a billionaire friend and asked how the two met.

That’s when Dunn told him about the Sebonack Golf Club connection to the WLNY purchase, Kennedy said in an interview. Kennedy said Dunn told him that, during the negotiations, Dunn asked Pascucci: “If I buy your TV station, are you going to give me two memberships to your country club?”

Kennedy said Dunn told him he was joking about the memberships. But he said Dunn told him that Pascucci came through when the transaction closed in 2012, presenting Dunn with two envelopes. One contained a club membership for Dunn; the other was intended for Leslie Moonves, then the powerful CBS chief. But Moonves refused the gift, according to Kennedy and a second person who was familiar with the details but was not authorized to comment. Moonves “didn’t want anything to do with it,” the second individual said.

While it’s common for a corporation like CBS to have viewing boxes in sports stadiums to entertain clients, a golf club membership is more difficult to share. CBS said it has no other golf club memberships.

If the swift departure of CBS Chairman Les Moonves has a bright side, it’s that a major television network took accusations of sexual harassment against its chief executive seriously enough to hold him accountable and obtain his resignation even at the expense of upending the management of its multi-billion dollar business.

Two other former high-level CBS executives said Dunn bragged about playing at Sebonack, and one recalled Dunn describing how he met Ross there during a golf outing with his son. A current CBS executive said Dunn described the membership as his own — not CBS’.

CBS’ 2008 Business Conduct Statement, which laid out the company’s ethics policies, advised employees: “We expect you under all circumstances to avoid any conduct or activity … which is likely to affect your business judgment.” The company said violations of ethics guidelines would include “soliciting or accepting money (or cash equivalents such as gift cards) for your personal benefit from a supplier.”

Gavin, who reviewed CBS’ ethics policies at The Times’ request, said the Sebonack arrangement appeared questionable. CBS said it benefited the company to have a membership at the golf club to host clients and business partners.

“Someone in [Dunn’s] position would have a fiduciary duty to do what is best for the company,” Gavin said. “How did this move benefit CBS stakeholders? It seems to have benefited a few people.”

After CBS bought WLNY, Dunn’s son went to work for another Pascucci venture at the mogul’s building on Long Island that housed the TV station, said Simmons and a second former WLNY employee who declined to speak publicly for fear of retaliation.

“I’d run into him in the cafeteria,” Simmons said of Dunn’s son. “A lovely young man.”

Michele Gillen was a reporter for CBS’ WFOR-TV Channel 4 in Miami. She sued her former employer, alleging age and sex discrimination.

In 2018, Pascucci sold the cybersecurity firm where Dunn’s son had worked, now called Skout Secure Intelligence, for $30 million to a company co-founded by another Sebonack member: Ross. In addition to the Dolphins, Ross is an investor in the Equinox and SoulCycle fitness center chains and owns upscale residential, retail and office buildings.

By then, Dunn had joined Ross’ extended family. Days after a July 31, 2017, divorce judgment with his first wife, according to New York court records, Dunn married Becky Gaffney Campbell, a Philadelphia native who is the younger sister of Kara Ross, the wife of Stephen Ross.

The night of the Aug. 4, 2017, wedding, the families celebrated at Sebonack. The evening was capped by a fireworks display, including flares that formed glittery red hearts over the Great Peconic Bay, according to an Instagram post by Kara Ross.

Before the wedding, CBS TV stations had been tasked with promoting Ross’ business during their local newscasts. Two CBS station executives said that in the fall of 2016, they ran a feature story to promote Ross’ $25-billion shopping and housing mega-development Hudson Yards as it began construction in New York City. “We were told we couldn’t change one word,” said Margaret Cronan, former news director at CBS’ Philadelphia station. The mandate came from the station’s group in New York, Cronan said.

During a three-minute segment from September 2016, the New York anchors gushed about Hudson Yards. “If anybody is going to do it, Steve Ross is the guy,” WCBS anchor Maurice DuBois said.

CBS declined to comment on its coverage of Ross.

After the CBS purchase, the Pascucci-era WLNY newsroom sets were donated to the Catholic Church, according to former employees. Most WLNY reporters and anchors were let go, and an on-air team delivered newscasts from WCBS’ studios in Midtown Manhattan.

CBS licensed pricey syndicated sitcoms, including “2 Broke Girls” and “Mike and Molly,” to run on WLNY and secondary stations in other markets. CBS said it expanded WLNY’s newscasts to an hour and has two reporters who report from Long Island for WCBS.

“The station remains an important part of the CBS Television Stations portfolio,” CBS said in a statement. “Since we acquired the station, we have upgraded its signal, increased the amount of local news coverage and programming and added more newsgathering resources.”

CBS launched a two-hour daytime talk show for WLNY in 2012, “Live From the Couch.” It, too, was produced in Manhattan by WCBS and lasted just two years. CBS hiked ad rates for WLNY’s airtime to pay for the programming, and longtime advertisers defected, Simmons said. CBS laid off most of its sales staff, including Simmons, in 2015, he and others said.

“They cut expenses and turned the station into ‘CBS-lite,’” said Diorio, who worked for CBS until 2014.

For nearly eight years following the purchase, CBS leased space from Pascucci at his Melville building to maintain a Long Island presence, even though no shows were regularly produced there, according to three former station employees. CBS confirmed the lease arrangement but declined to provide details. Its FCC license still lists Pascucci’s building as WLNY’s main studio address.

“That station was always a throwaway for them,” Simmons said. “It was just a nice little thing for CBS to have to extend their reach and extend their power.”

Read the second part of the Times investigation into the CBS TV stations group here.

Staff researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.