In the summer of 2013, Al “Bubba” Baker was at a crossroads.

The retired NFL defensive end was running Bubba’s Q, his family’s popular barbecue restaurant in Avon, Ohio, and plowing those slim profits into another venture built on his invention — boneless baby back ribs that were sold in several local supermarkets.

But Baker’s dream of taking his boneless ribs business nationwide, while expanding his branded line of sauces and rubs, was teetering. He almost called it quits.

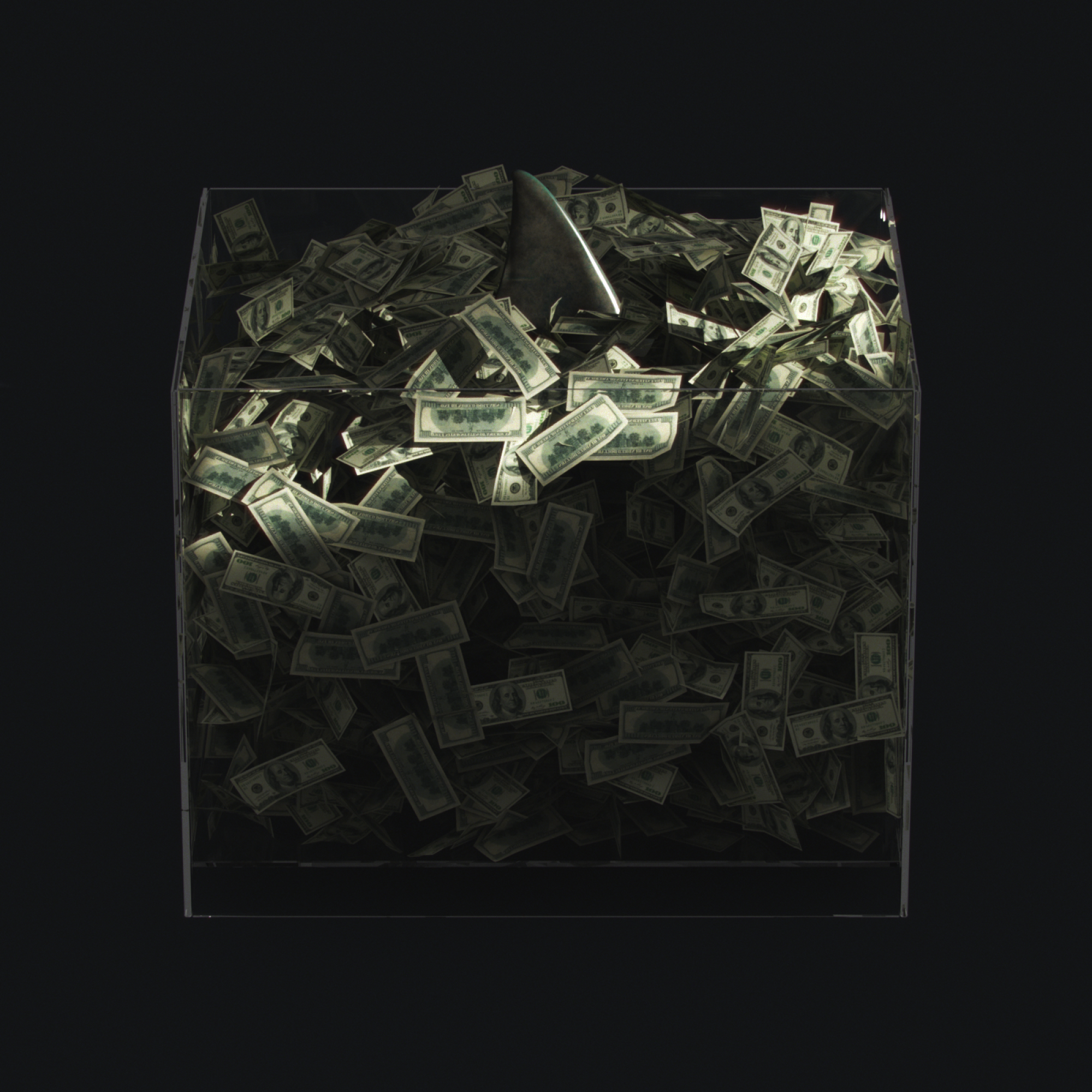

His daughter, Brittani Bo Baker, wasn’t ready to give up. She found inspiration in her favorite TV show, the ABC reality series “Shark Tank.” A parade of contestants on the program, pitching a quixotic array of products including insect repellents and sleep pod blankets, was snapping up big-money deals and instant fame.

“This is going to help us,” she told her father, nudging him to apply for the show.

Baker, 66, had appeared on the TLC competition show “BBQ Pitmasters” and on PBS’ ode to small business, “Start Up.”

At first, he was skeptical. But as he watched “Shark Tank,” it hit home.

“The show was putting itself out there as the American dream,” he said.

By September 2013, Baker and his daughter were in a TV studio in Los Angeles, wooing the panel of celebrity shark investors with their story and rib samples for the show’s fifth season.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Towering over the star investors at 6 feet 8, Baker impressed the panelists, pulling out his patents from behind a stage prop.

“Football was my job, but barbecue is my passion,” he told them.

After the usual shark banter and grilling, Baker accepted fashion mogul Daymond John’s offer: $300,000 in return for a 30% cut of the company (over Canadian multimillionaire Kevin O’Leary’s play: $300,000 for a 49% stake), contingent on finding a licensing deal with a large meat processor.

Within three years, Baker and his Bubba’s Q Boneless Baby Back Ribs were being promoted on the show and various press accounts as one of the biggest “Shark Tank” success stories, generating $16 million in revenue.

During a “Shark Date” update episode, John said of Baker’s ribs, “I still believe that this will potentially be my biggest deal ever.”

“This was going to change our lives.”

— Al ‘Bubba’ Baker

However, the Bakers say the reality that unfolded was far different. They say they’ve received just $659,653, barely 4% of the business’ publicized revenue.

What began as their “Shark Tank” dream, they say, “has been a nightmare.”

The Bakers accuse John and some of his associates and partners — including one former contestant facing felony charges — of misleading them, trying to take over their business and depriving them of the profits from potentially lucrative partnerships.

According to the Bakers, John and his representatives ceased communicating with them until last month, when The Times made inquiries, and stopped promoting a product that once sold in 1,400 locations and is now hard to find.

Baker’s big plans for success and riches have stalled, and legal battles have bled his family’s savings. Baker has shuttered his restaurant; after renting out his house, he was forced to sell it at a loss, and his truck was repossessed.

While the Bakers’ experience is perhaps extreme, it highlights the unique perils of reality TV programs. Over the years, “Shark Tank” has drawn scrutiny as other contestants have raised questions about its image as a kind of venture capital spinoff of “Top Chef.” A recent survey by Forbes of 112 former contestants found that nearly half of business deals offered in seasons eight through 13 fizzled.

Baker says he was blinded by the idea that he was going to make millions, but he reserves much of his disappointment for John, someone he considered “family.”

“I was super proud of my relationship,” he said. “I just never expected economic marginalism from another African American.”

John declined to respond in detail to a number of questions, citing a “confidentiality agreement” with Baker. John said he lost money on his investment and denied taking advantage of the ex-NFL player.

In a statement, he said: “We have to decide if we want to legally pursue them. Even if we win, what is the real benefit of taking money from a small business?”

The investor rebuffed the Bakers’ claim of being misled, saying they had legal representation and business advisors during negotiations. Baker, he said, made “significant revenue through the history of the venture. We did not and have not.”

Additionally, John said the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the business. There was limited product for him to promote, he said, and the Bakers were aware of “razor-thin margins” in the food industry.

“No matter how disappointed, frustrated or insulted I may feel about a person or company, I signed up and remain on ‘Shark Tank’ to uplift people and give them a shot that I never had,” John said. “Bad business decisions do not make an entrepreneur a bad person.”

An ABC spokesperson said the network declined to comment. Representatives of MGM Television and Sony, which produces the show in association with MGM, also declined to comment.

“Shark Tank” has been a hit since its 2009 debut. The Emmy-winning series, based on the British show “Dragons’ Den,” is adapted from the Japanese series “Money Tigers.” Iterations of the program air in some 30 countries.

The American version is produced by Mark Burnett, who built a reality TV empire with shows such as “Survivor” and “The Apprentice,” which transformed Donald Trump into a household name, buffing his reputation to a high gloss of wealth and legitimacy. Burnett did not respond to requests for comment.

“Shark Tank,” which airs Friday night, has averaged 4.3 million viewers in its 14th season and was just renewed for a 15th season. Reruns air on CNBC; it’s also streamed on Hulu. Thousands of small-business owners vie each year for a spot to pitch their ideas before six panelists, including Mark Cuban, Barbara Corcoran and Daymond John — other celebrity investors like Goop mogul and actress Gwyneth Paltrow rotate in — and the chance to land deals that could make them millionaires.

The show presents an idealized version of capitalism in which anyone with an idea, hard work and determination can make it to the big leagues — underscored by several bona fide success stories, including the apparel company Bombas, a John investment, and the toilet product Squatty Potty.

“This thing was going to change our lives,” Baker said.

In 1978, Baker was drafted to play for the Detroit Lions. During his first season, he was named defensive rookie of the year. Before he retired in 1990, Baker played for the St. Louis Cardinals, the Minnesota Vikings and the Cleveland Browns.

Baker had a reputation as someone who “menaced and mauled opposing quarterbacks,” as one sports reporter wrote. Off the field, he became well-known among fellow players for preparing and selling barbecued turkeys and ribs.

As a child, Baker had learned the art of smoking meats from his uncle “Daddy Jr.,” spending summers at his famous Jacksonville, Fla., restaurant, Jenkins Quality Barbecue.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Later, Baker came up with a way to remove the bones after cooking, allowing the sauce to permeate the meat without losing its flavor. His inspiration was his wife, who found ribs too messy. The boneless ribs could be reheated in the microwave and eaten with a fork and knife. He patented the rib in 2007 and the cooking process in 2011.

“We were taking the bones out of a slab of rib,” he said. “I mean, this wasn’t McDonald’s.”

The Baker family rented the processing facilities of a local supermarket and manufactured the ribs overnight when the store was closed. It was taxing work.

Baker’s dream was to secure a deal with billionaire investor Mark Cuban. “He’s got all the money,” he said.

If not Cuban, he hoped for “Queen of QVC” Lori Greiner; but Cuban declined to bid, and Greiner did not film that episode.

Baker hadn’t seriously considered Daymond John — he’d never invested in a food company.

But the family had big dreams and mounting expenses. And they’d come this far; only a fraction of aspiring entrepreneurs received a shot on the show.

“We got a star on a TV show to talk about us,” Baker said. “I mean, you don’t come that far and go out to L.A. and be half in. And I was sold.”

THE “PEOPLE’S SHARK”

Daymond John, 54, flawlessly dressed and charismatic, calls himself the “people’s shark.”

In 1992 he co-founded hip-hop fashion company FUBU, as he has said, with a $100,000 loan on his mother’s house in Queens, N.Y., where he sewed hats that he sold for $10 apiece. By 1998, the company reportedly made $350 million in annual revenue.

Since then, John has leveraged his reputation as a scrappy self-starter and his association with the show into an ever-growing portfolio of businesses, motivational speaking, books, seminars and a dizzying array of products under the umbrella of his firm, the Shark Group. In 2015, President Obama named John a Presidential Ambassador for Global Entrepreneurship.

But over the years, John or his companies have faced lawsuits — including by at least two former “Shark Tank” contestants — in New York and Florida, including claims for breach of contract and deceptive business practices. Some cases were settled, others dismissed.

In 2010, Alan Kaufman, a contestant on the first season of “Shark Tank,” sued John, ABC, Sony Pictures Television and the producers of the show, claiming that it fraudulently portrayed John as a successful entrepreneur and a “legitimate potential investor,” without disclosing his “prior history of breaching contractual agreements,” citing seven lawsuits against John and his businesses over deceptive business practices and other claims.

Kaufman alleged that John and then-shark Kevin Harrington (who was not named in the suit) agreed to invest $100,000 each for 51% to market his “souped-up umbrella design” on the show, but his “interest proved to be insincere,” and that he did little to help beyond suggest a business partnership with bankrupt retailer Sharper Image.

Mark Cuban plays a tough negotiator on ABC’s “Shark Tank.”

He further alleged that John threatened to pull his investment if Kaufman did not appear on a follow-up show. Kaufman, who died in November, settled for $20,000, according to court filings.

John said such lawsuits were “common for public figures,” adding that “in the 30+ years I have been in business, there is not one lawsuit that I have been involved in where I have been found guilty or culpable of anything.”

In 2020, John prompted controversy at the height of the pandemic when it was widely reported that the Shark Group struck an “unusual arrangement” with the Florida Division of Emergency Management to sell 1 million N95 masks at $7 apiece.

3M, the manufacturer of the masks, went public saying John’s company was not authorized to distribute them and that the cost offered was three times the market price. The deal fell apart.

At the time, John issued a statement on Twitter criticizing the news reports, saying that he did not set prices and was trying to help. The Florida agency’s director publicly supported John’s efforts.

After their on-air handshake, things moved quickly for the Bakers.

A golf cart shuttled Baker and his daughter into a trailer where they met with a woman from John’s team. Baker said she produced a three-page exclusivity contract for 18 months.

“There was no time, no attorney. [She] just came in and put it in front of us,” Baker said.

According to John, this “no shop” agreement was standard to prevent entrepreneurs from leveraging their episode to “do business with another third party without discussing with the Shark.”

Baker said they’d signed several waivers and nondisclosure agreements to be on the show, including provisions that allowed ABC to portray contestants in any light or fashion.

“You’re in that environment, you are not asking a whole lot of questions. It’s Daymond John,” he said. “My wife and daughter would have killed me if I said I wasn’t signing this.”

Within weeks after returning to Ohio, the Bakers said, John called and informed them that he was revising deal terms. Instead of the $300,000 for 30% struck during the taping, John would invest $100,000 for a 35% stake.

A source familiar with the show who was not authorized to comment said this often happens once the panelists have the opportunity to vet the businesses.

“The deal terms that aired were contingent on securing a licensing partner, which did not come to fruition,” John said. “When we do deals on Shark Tank, these are based on 45-60 minute oral pitches with people who present well on TV on their ‘first date’ who are only providing their word and no written documentation to their business and its state of play.”

Baker disputed John’s account, noting that he found a licensing partner and that the investor cited other reasons for changing the deal that “didn’t make sense.”

“Shark Tank” producers told them they could not guarantee when or even if their episode would air. Contestants often reported a sales spike after appearances on the show, but the producers had cautioned the Bakers against taking any drastic steps.

Nonetheless, John counseled the Bakers to do just the opposite, recommending they build an e-commerce site to capitalize on huge interest the show would draw.

John introduced them to Nate Holzapfel, describing him as “an internet genius” who could help them take advantage of the TV bump, the Bakers said.

Holzapfel, then 34, had been a contestant on the previous season of “Shark Tank.” He pitched his Mission Belts Co., calling it “a belt with no holes, that always fits.” John agreed to invest $50,000 for a 37.5% stake in the Utah-based company, which reportedly sold $180,000 worth of belts the night Holzapfel’s episode aired.

Holzapfel became John’s protégé, working with him on other “Shark Tank”-related ventures. Soon, he was offering his expertise to entrepreneurs through a series of coaching, training, videos and books, under his website “Nate State of Mind.”

At first, Baker welcomed Holzapfel’s involvement.

“We had never sold one bottle of the sauce on the internet,” Baker said. “This was going to be the ‘genius’ to set us up.”

But problems surfaced immediately, according to the Bakers. The website wasn’t operational until three hours before their episode aired.

Days after appearing on “Shark Tank,” Baker said, they hauled in $250,000 in online orders — nearly double his sales of ribs the previous year.

The restaurant was receiving 600 calls a day, and when someone recognized him at the airport, it was because of the show, not his football career, Baker said.

But the euphoria was short-lived. The Bakers said they had to refund to customers nearly 14% of the amount of the initial online orders because Holzapfel failed to install a feature to collect sales tax on certain products.

“Mr. Holzapfel does not have any comment on this matter,” Nathan Crane, an attorney for Holzapfel, said.

John said he didn’t recall referring to Holzapfel as a “genius” and said Holzapfel “had a very successful evening from an e-commerce perspective when his Shark Tank episode aired.”

John acknowledged there were problems the night of the Bakers’ episode, saying that it is difficult to prepare for “the wave of traffic” that follows an episode. “We put Nate in charge of this task, and the site was very successful,” he added.

Holzapfel also managed the business’ bank account. Although the Bakers went along with it initially, they said in retrospect that it was an overreach of his role.

Whenever he asked for financial statements, Baker said, Holzapfel ignored him.

‘Shark Tank’

After Baker complained to John about Holzapfel, he said, the panelist responded: “I’m not asking you to kiss him. You know, this is business.’”

Baker knew his business had been transformed. He no longer had to work 100 hours a week running his restaurant and managing the manufacturing of the ribs. But he had no idea how well it was doing. He thought Holzapfel made millions. John made even more millions. He wanted to make millions too.

“I’m from a small town, Avon. Maybe this is how people act,” he reasoned. “I didn’t want to mess up this great deal.”

Weeks later, the Bakers flew to New York to meet with John at his offices in the Empire State Building. Bubba looked up from the sidewalk, believing he’d arrived.

“You can imagine us, we’re kind of like ‘The Beverly Hillbillies’ in downtown New York,” Baker said. “He’s on the 66th floor.”

During a meeting, they were introduced to Larry Fox, who handed Baker his résumé. It showed that Fox had an accounting and legal background, but Brittani said it wasn’t clear what Fox’s role was in John’s business empire.

Only years later, Baker said, did he learn that Fox was John’s lawyer and how involved he was in the enterprise John set up to sell his boneless ribs.

John said it was “absolutely untrue” that the Bakers did not know Fox was his attorney, or that they were not informed of his role in the ribs venture.

Fox is listed as president of Shark Sports Management, John its chief executive. According to its website, the former corporate attorney has been a licensed NBA agent since 1995 and serves as the general counsel of John’s Shark Group, as well as his personal attorney.

Returning to Ohio, the Bakers said the problems with Holzapfel continued.

Ammie Black worked for Holzapfel doing customer service for the websites of Bubba’s Q Boneless Ribs and that of Garage Door Lock, a company founded by another “Shark Tank” contestant, Bryan White, who had made a deal on Shark Tank with John. She began in December 2013 and resigned five months later.

Black said the Bakers were largely kept “out of the loop” and that Holzapfel controlled the site and the bank account. “He was the only one who had access to those,” Black said.

“Where’s the money?”

— Al ‘Bubba’ Baker

Black described her tenure with Holzapfel as problematic. For one, she said, he paid her for work done for the Bakers with the Garage Door funds and vice versa.

In addition, she said Holzapfel would put promotions on the website that he couldn’t fulfill.

Black outlined many of her concerns in an email to Brittani Baker and in her resignation letter to Holzafpel. Copies of both were reviewed by The Times.

White, the founder of Garage Door Lock, was also baffled by Holzapfel.

John had struck a deal with White to invest $275,000 for 35% of his business contingent on finding a licensing partner, but White said John “didn’t hold up his end of the deal and maybe he couldn’t.”

After meeting Holzapfel, White said he told John, “If you knew what is good for you, you would keep your distance from this guy.”

“I don’t remember this,” John told The Times.

John noted that it was common for deals to change after filming for “due diligence” and said “Nate was one of our top sales people which aligned with Bryan’s interest in growing sales.”

After working with Holzapfel for about seven months, the Bakers had enough and no longer wanted to work with him. But John defended Holzapfel’s work, they said, and told them all businesses had “hiccups.”

At one point, Brittani said, she briefly had access to the bank account and noted it had about $100,000 on deposit.

In June 2014, the Bakers said, Holzapfel closed out the bank account and sent them a check for $8,000.

“I said, ‘what happened to the rest of the money?’ And he [John] said, ‘Nate deserved it,’” Baker said.

“This was close to ten years ago and I don’t remember,” John said.

Holzapfel is out on bail awaiting trial in Utah on 15 felony and five misdemeanor criminal charges filed in 2021 and 2022, including communications fraud, theft and forcible sexual abuse, according to the Utah County attorney’s office in Provo.

The charges stem from eight cases involving multiple women between 2018 and 2021. Utah prosecutors say that the married Holzapfel struck up romantic relationships with “vulnerable” women he met on dating apps, then convinced them to turn over their money and assets.

Holzapfel has not entered a plea on the charges. A preliminary hearing is set for July 14.

His attorney declined to discuss the charges and other claims against his client.

John said he has not had “any relationship” with Holzapfel in years. “He ended up showing a pattern of bad habits and he was not a fit for how we do business,” John said, adding that he only became aware of Holzapfel’s legal predicament “after we ended our relationship with him.”

A BIG RIBS DEAL WITH CARL’S JR.

By 2015, Baker put his dispute with Holzapfel behind him.

He had met with Rastelli Foods Group, a family-owned manufacturer, in Swedesboro, N.J. According to Baker, the Rastellis represented themselves as a $400-million company that had the capacity to produce Bubba’s Q boneless ribs at scale.

The Bakers said they were impressed with Ray Rastelli III, the company’s vice president.

“The company is now a strong 100 million dollar brand and growing at 100% each year. I think the potential for our rib is even bigger,” he wrote in an email reviewed by The Times.

The Bakers agreed that Rastelli Foods Group would produce the ribs and sell, distribute and market them; it would also handle their business’ accounting. In exchange, the Bakers would earn a licensing fee and 45% of the net profits.

When he briefed John on the new deal, he said, John told him that he needed to be connected with Rastelli.

Baker, however, wanted to keep each side separate: He would handle the manufacturing, and John would continue as brand ambassador.

But in a long email to Baker viewed by The Times, John insisted that he be introduced.

“I am beginning to understand how much you do not understand what working with Shark Tank is doing for you and your business,” he wrote in May 2015. “You are part of the shark tank family. You and anybody that you have put on camera is now my personal responsibility. I have to report back everything I can to keep Shark Tank producers and ABC up to date.”

He added: “You will no longer be of interest to the show to promote because there is another season about to be shot and every Shark has their top 5 Bubbas of the world they are trying to keep promoting.”

John said it was important for him to meet with the Rastellis “to see if I felt they were a fit for the business before doing anything, including putting them on an update on the show.”

Baker relented. “It was like, ‘Al, don’t do something to screw this up. This is Daymond John.’ And he was really trying to get to Rastelli.”

Baker agreed to include John in a three-way partnership with the manufacturer. They called the new venture FOF Bakers LLC (FOF stands for Full of Faith). Baker was the managing partner, with a 45% stake and 100% owner of the patents; Rastelli got 35% and John 20%, Baker said.

“We were getting $20,000 and $25,000 checks. We thought this was only going to improve,” Brittani said.

Baker began selling Bubba’s Q boneless ribs on QVC, appearing at least once a month. During his segments, he said the product often sold out and sometimes appeared two or three times on the network.

According to the Bakers, Fox was involved in nearly every aspect of the business, such as sending sales projections.

In December 2015, Fox sent the Bakers projections, telling them that by March 2016 the company would generate $74,707 a month in profits, according to a document viewed by The Times.

“All information for the basis of any projections were provided by the Rastellis,” John said.

Rastelli said he could not disclose confidential information about customers.

Believing that his American dream was within reach, Baker rented out his house in Ohio (which he sold at a loss), left the restaurant for his children to run, and he and his wife moved to Clearwater Beach, Fla. They rented a condo and began looking to purchase a multimillion-dollar home.

But months after the partnership was formed in October 2015 the Bakers said the payments dwindled considerably.

Now, Baker said, John, Fox and Rastelli were making all of the decisions, excluding him.

Baker began asking questions. Lots of them. Starting with, “Where’s the money?”

The Times viewed copies of several of Baker’s emails to both Larry Fox and Rastelli Food in which he asked for financial transparency as well as the details of decisions that were made without him. In one email, he wrote, “I have some financial concerns and a 14-month period of no profits in the form of disbursements make this something that needs to be discussed in person.”

“You will no longer be of interest to the show.”

— Daymond John

When the Bakers brought their concerns to Fox, they said he rebuffed them, asking, “why do you want to know all the minutiae?”

Baker said they simply placated him, telling him about big potential deals coming and having him appear on various update segments and press events.

Fox disputed that the Bakers were kept in the dark about finances.

“Managers like Al have, and have had, direct access to accounting and financial information,” said Fox in a statement through his representative. “Non-Managers like us have not.”

According to John, Baker and Rastelli were responsible for all accounting, records and business decisions, adding that “Al and his family had more direct access to all accounting information” than his company, he said.

In April 2017, things took a positive turn. Carl’s Jr. and Hardee’s launched a limited campaign to sell a Baby Back Rib Burger, using Bubba’s Q de-boned ribs at 3,000 franchises nationwide — a deal worth $5.8 million. The Bakers were ecstatic, believing this was finally going to propel them out of the red and into some serious money.

According to Baker, he had met the chain’s representatives at a food show in Chicago a year earlier. But Fox and Rastelli handled the negotiations and he was kept out of the discussions. In December 2016, Ray Rastelli III wrote to the Bakers and Fox that the deal “should generate minimally about [$]300,000 in profits for our company with the potential to be much more,” according to the email viewed by The Times.

The Bakers estimated they would earn at least $193,000 from the deal, including licensing revenue. Instead, they collected $2,900 in net profits and a $61,917.45 licensing fee. They said no explanation was given for this discrepancy and they were told that all parties earned the same amount, which they said conflicted with the split outlined in their agreement.

“That’s when we were like, ‘We don’t want to do any more big deals until we can get this straight,’” Brittani said.

Rastelli declined to respond to questions about the claimed discrepancy in net profits.

When Rastelli proposed another deal with an international sandwich chain, Baker refused to move forward until his questions were answered about the Carl’s Jr. deal and other accounting issues.

In 2019, Rastelli Foods sued the Bakers in the Superior Court of New Jersey. Fox joined the suit on the side of Rastelli Foods.

Rastelli alleged that Baker refused to participate in meetings and other obligations, “in violation of his fiduciary duties,” and that he imperiled the deal with the sandwich chain.

The lawsuit stated that they had provided Brittani Baker with financial information and offered her access to their software system.

However, Brittani said the reports were incomplete and that Rastelli executives rebuffed her request to fly to New Jersey to learn the software system. The company sent her an email, which was viewed by The Times, canceling her training, citing confidentiality concerns.

The case went to arbitration and mediation in 2019. As part of a settlement, the Bakers were to receive a larger share of gross profits, and Rastelli agreed to pay them $100,000 in 12 installments. The parties acknowledged that the business had accumulated gross receipts of $14.5 million.

All parties would work together on potential deals and other matters, and agree to financial transparency, states a copy of the agreement viewed by The Times.

However, the Bakers say they still aren’t included in important discussions about the business, which hasn’t been sold. And they say their post-settlement profits have shrunk further; they received $553.35 for the first three months of this year. The Bakers are still paying off $171,000 in lawyers’ fees.

In a statement, Ray Rastelli III declined to respond to many of the Bakers’ specific claims, citing confidentiality agreements.

“Rastelli Foods Group is one the nation’s leading high-quality food suppliers. We’ve built our professional reputation on a culture of ethical behavior and upholding our agreements,” he wrote. “As such, we are again dismayed by the Bakers’ ‘allegations,’ which are untrue.”

He said his company “had been paying all the costs of bringing the product to market.” But after early successes, high production costs and pricing challenges affected sales, causing retailers to drop the line, Rastelli said.

The slowing sales, he added, prompted the Bakers to send a series of “threatening inflammatory letters and emails” in 2019, which the Bakers denied.

“We have repeatedly requested access to real-time accounting since the beginning of our partnership, yet these requests have been continually and continue to be ignored,” Brittani said.

The Bakers say they shied from legal action because of the cost required to hire a forensic accountant and a lawyer in New Jersey.

“We didn’t have the money,” Baker said.

Others shared similar complaints about John and “Shark Tank.”

In 2015, then 20-something friends Jordan Barrocas and Dan Fogelson appeared on season seven of “Shark Tank,” eager to cut a deal to expand their business, Three Jerks Jerky. The pair had launched the business two years earlier with a $20,000 Kickstarter campaign, and they had been selling their gourmet filet mignon beef jerky in 41 stores nationwide.

They struck a deal with Daymond John, who offered them $100,000 for a 15% stake with an option to inject another $100,000 for an additional 15%.

The thrill of the deal turned to elation when their episode aired in October 2015 and they sold $250,000 worth of jerky. Three months later they reported that sales hit $1.4 million.

But within three years, Three Jerks Jerky was in debt. Barrocas and Fogelson were no longer involved in the business they founded, and their friendship was strained.

According to Barrocas, soon after taping their episode, John revised their deal. Instead of infusing needed capital into the business, John would only commit to “open doors” in exchange for a 5% royalty based on sales. Shortly after that, Barrocas said John pressed the pair into quickly agreeing to a 50-50 partnership split between them and John and Rastelli, dangling the promise of future “Shark Tank” appearances.

In addition to manufacturing the jerky, Rastelli would handle their accounting and would sell them raw meat for their product.

“It was a very powerful TV show, and we got a lot of visibility and exposure,” Barrocas said. “But my expectations and perceptions of the investment landscape were very different than the reality we experienced.”

John said the terms of the deal changed as a result of “due diligence,” adding that the equity and dollar amounts cited are not accurate. He declined to provide figures.

He said all parties were aware of the roles and responsibilities outlined in their operating agreement, which was reviewed by legal counsel. John denied imposing any deadlines and said he “lost money on the deal.”

Rastelli declined to comment on Three Jerks Jerky, citing their “confidentiality agreement.”

As for Baker, he said he has spent a lot of time reflecting on how things have unfolded. The business, he said, is largely at a standstill.

“I have reconciled with it, and I don’t care what this looks like,” Baker said. “I care about the truth. And a lot of why I was being quiet was because I looked like a stupid fool character. I’m past that. And I’m concerned about other people coming along with their American dream having this happen to them.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.