As the writers’ strike lingers, TV showrunners are opting out of publicity for their work

Every Wednesday night since early February, D.J. Nash, the creator of ABC’s “A Million Little Things,” regularly tapped out scads of Twitter posts to his more than 14,000 followers, live-tweeting during new episodes of the tear-jerker drama. The series was in its final season, making his routine, which he started after the show launched in 2018, all the more important.

Two days before the series finale was set to air on May 3, movie and television writers went on strike after contract negotiations between the Writers Guild of America and major studios ended without a new deal in place. Although the finale aired as scheduled, Nash told viewers that he wouldn’t be discussing it: “The writers are on strike, so in support of the WGA, I am going to step away from promoting any shows I worked on. Which is hard,” he wrote in a tweet.

Instead, in the hours before the series finale, he joined his colleagues on the picket line outside Disney Studios in Burbank, hoisting a protest sign. And by airtime, he settled in for a new approach to his routine.

“I did screenshots of my Twitter feed,” Nash told The Times. “One day, I hope to respond to each [tweet] more specifically. But I had 112 pages of tweets just to me, and more to our series where I wasn’t tagged. There are things about the finale that I would be really excited to share with the fans and say, ‘That was for you, thank you for watching,’ and I haven’t had that chance.”

It’s a circumstance many writers are facing since the strike began. Accustomed to promoting the creative projects that they and their teams have doggedly worked on over many weeks and months, some writers — including marquee names — are withholding their participation in the publicity machine to add further pressure on the studios to resolve the strike.

In a guest column, the first-time showrunner and creator of Amazon Freevee’s ‘Primo’ says writers are asking for reasonable accommodations that help make writing a viable career path.

The work stoppage follows months of tense negotiations. The WGA has proposed demands collectively valued at $429 million, including increases in minimum pay and increases in residual payments from streaming. The union and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, the organization that represents the major television and film studios, networks, streaming services and production companies, have yet to reach a consensus in contract negotiations and both sides have signaled that they remain far apart.

The Times reached out to the AMPTP to ask how studio executives felt about the promotional blackout taken by some writers during the work stoppage, but they declined to comment, saying they couldn’t speak for individual studios.

Nash, who is a strike captain for showrunners during the work stoppage, argued that although he and others were unable to bask in the culmination of years’ worth of storytelling was unfortunate, it was also necessary.

“I remember Shawn Ryan [the TV writer and producer] during the last strike had to walk away from the last episode of ‘The Shield,’” he said. “We all are doing this not for ourselves. We’re doing it for the generation of writers who come after us, the way that writers before us did it for us. And how can you not do that? So it really wasn’t a question.”

The 2023 writers’ strike is over after the Writers Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers reached a deal.

So if you were curious as to why “Barry” co-creators Bill Hader and Alec Berg chose that shot for the closing moments of the series finale, or if you wondered how Jesse Armstrong and the “Succession” writers pieced together an election-night episode that felt very familiar, or if you hoped to know where “Yellowjackets” was heading with its finale after the brutal fight in Episode 7 — it might be a while before you get answers. And if you happen to read an article in which a writer is discussing a project, the interview likely took place before the strike.

Most writers are refraining from press interviews for their shows, promotional events organized by networks or studios, and from posting on their own social media accounts, where they would boost awareness about their work. This includes projects that were completed before the strike and those that are currently in production — though some shows have stopped production because of the strike.

Still, in a media environment where the line between promotion and water-cooler conversation is not always clear, writers are not necessarily certain what is, or isn’t, within the rules.

A spokesperson for the WGA directed The Times to the FAQ section of the strike rules under the question, “Can I promote my project at a film festival or at a ‘For Your Consideration’ event about the film or show I wrote on?” The guild advises, “No. You should let the Company know you are prohibited from making these promotional appearances about your work until the strike concludes.”

Streaming has transformed television and led to a surge in content, but it also has squeezed Hollywood writers. Five Writers Guild of America members share their stories.

A source who works with writers and who requested anonymity in order to share private communication, pointed to updated guidance from the guild that appeared to leave the door open for some promotion. It read: “[I]f they wanted to promote their work on their own accord, that would not be prohibited, so long as they aren’t interacting with struck companies or appearing alongside company execs at a press event.”

Underscoring the delicacy of the situation, several writers who spoke to The Times were quick to note their concern that participating in this story would go against their decision to withdraw from publicity that could be tied to their projects.

Previously, television writers were figures whom viewers rarely knew by name, but they nevertheless played an important role in the success of a series. But in this current era of television, writers, particularly series creators and showrunners, are more firmly in the spotlight. They’re often known entities whose star power is just as significant to a show’s viability as the acting talent. And insight into their overarching creative vision and narrative choices has become a crucial element in the ecosystem of publicity for new and returning series.

News and entertainment outlets, including our own, have had to pivot some angles of coverage for which knowing a writer or showrunner’s perspective was key to understanding the essence or goal of a TV or film project.

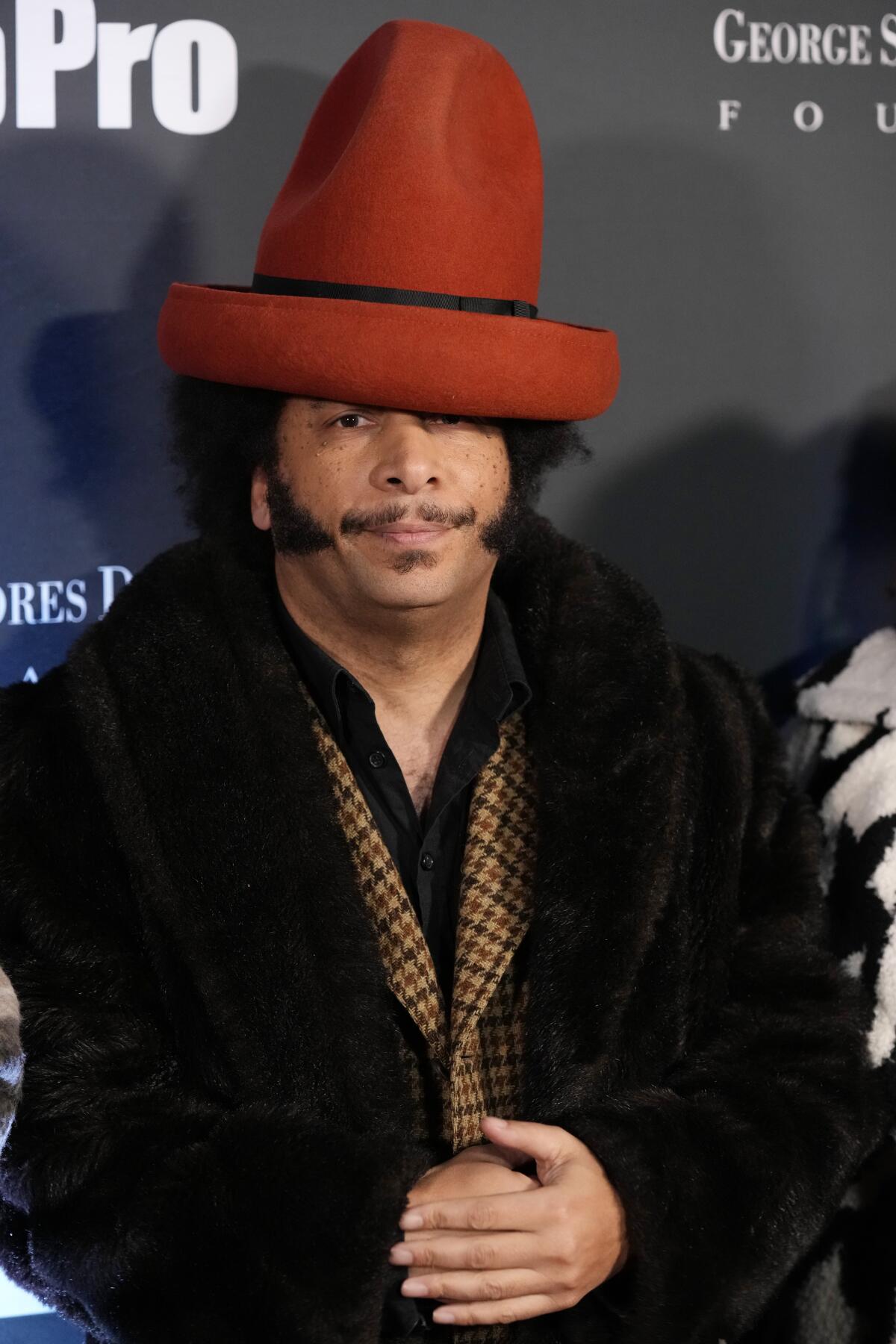

Boots Riley, the writer and director of the 2018 film “Sorry to Bother You,” did not hesitate to withhold his participation from publicity early on, even with his first TV series, “I’m a Virgo,” set to launch on Amazon next month.

“It’s a tactic to try to get the gears to grind to a halt,” he said. “That’s a sacrifice. And that hurts a little. But think about all the stories that writers write about people doing right and people doing wrong. Now, this is the real world. This is representing that real sacrifice. It wouldn’t be a strike if we weren’t sacrificing something.”

Riley said the strike is more important. One way he’s looking at it is that it’s a part of his effort to make art that lasts forever.

“That’s what all writers are doing, trying to touch eternity — ‘I was here. This is what life is like, this is what humanity is. I did this.’ What we are doing, though, is part of what sets the context of that work,” he said. “This fight, what we’re doing in our lives, this is telling the story. This is telling a story that’s going to last and touch generations.”

Teamsters Hollywood Local 399 boss Lindsay Dougherty has caught the attention of the labor movement with her forceful rhetoric. Her sometimes profane style has drawn out some critics.

For Katori Hall, the creator and showrunner of Starz’s “P-Valley,” the no-promotion allegiance arrives at an interesting time. The writers room had already closed for the third season of the pole-dancing workplace drama; prep work for filming was supposed to begin about a week before the strike went into effect, but now it has been delayed and production has not begun on the series. Meanwhile, Emmys season is in full swing, and Hall would ordinarily be expected to participate in for your consideration events, at which showrunners pitch their work for awards. But these will proceed without her involvement.

“Because I don’t have new episodes airing, I kind of lucked out in terms of the timing of it all because the second season, it’s out there in the world,” she said.

Although she’s able to take a much-needed break in what would normally be a time chock-full of promotional events, she expressed concern about what it could mean for writers of color, like her. However, she also believes it’s an opportunity to give other voices the spotlight.

“At this point, I know for me, I am stepping back from those duties and allowing those who can speak up to be on those panels,” she said. “I think it’s kind of this double-edged sword though, right? Because how many Black female showrunners are there out there?”

Here are all of the awards shows and entertainment events that have been affected by the writers’ strike.

The effects of the strike and the promotional work stoppage on writers and creators of color, who traditionally face extra barriers to entry in the industry and often see their work and stories ignored or undervalued, particularly when it comes to the marketing and promotion of series, is a concern for Hall and others.

“It’s just one of those things,” Hall continues, “whether it is a virus or a strike, when there is a work stoppage, those of us who are of color, who are marginalized, who have not always been represented, we are always more vulnerable and more susceptible to the detrimental effects of these things. And that is just wrapped into the history of our world. And so while I do, from my perspective, find it frustrating, I think we have gotten very creative and that it’s, like, “OK, Katori can’t always be the person who has to speak up, so who’s up next?”

The dilemma is also top of mind for Gloria Calderón Kellett, who regularly champions her work and projects made by other Black, indigenous and people of color on her social media accounts. Whether the incremental gains made in representation on TV are at risk of being eroded or lost in this moment — and whether some shows will survive when the strike is over — are concerns Kellett reflected on. But she remains hopeful that the outcome will be worth it.

“It’s not the guild‘s fault. What the guild is saying is the sooner we stop everything, the sooner this ends,” said Kellett, the creator of Amazon Prime’s “With Love.” “The sacrifice is for the betterment of the industry, but the cost is just undoubtedly more difficult to bear for all the underserved communities fighting for their mere existence on screen. ... So it’s crucial that we fight for ... the fair treatment of writers, but in that, also understand that the representation in the industry is still rough. [We have] to be mindful of those challenges and setbacks when this is over.”

Kellett said that she continues to evaluate what feels appropriate and respectful. She recently appeared at an intimate event for the Season 2 launch of her series, but she did not give a speech before the screening.

The promotional silent treatment by Hollywood writers largely carries on for now.

“We’re wanting to starve the monster as much as we can starve the monster so that it understands that we nourish it, and it needs us,” Kellett said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.