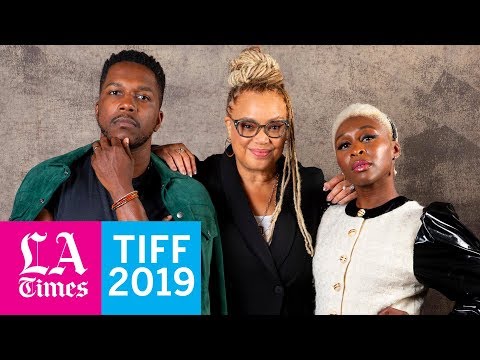

Don’t call ‘Harriet’ a ‘slave movie’: Kasi Lemmons and Cynthia Erivo made a ‘freedom story’

- Share via

One of the final scenes of Kasi Lemmons’ “Harriet,” a biopic about the runaway slave turned abolitionist Harriet Tubman, required its star, Cynthia Erivo, to climb a cliff in full period dress.

“Period shoes, corset, everything,” she recounted over breakfast in Beverly Hills, shortly after the film’s world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. “I think we did 12 or 15 takes. I collapsed at the top. The guy who owned the property was like ‘I don’t know how you’ve done it, it’s amazing.’”

“We put her through so much,” said Lemmons ruefully. “I’m like, ‘OK, climb the cliff. Again. Now let’s shoot it from the top. Again.’” She laughed.

The film, which exceeded box office forecasts when it debuted to $12 million over the weekend, marks the first leading role for Erivo, who stole scenes in last year’s “Widows” and “Bad Times at the El Royale.” Lemmons, best known for writing and directing the 1997 Southern gothic drama “Eve’s Bayou” (which was inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry last year), was handpicked by producers Debra Martin Chase and Daniela Taplin Lundberg to direct the picture.

“When they told me about it, I realized that my heart was pounding and that I felt fear and excitement,” Lemmons said. “I felt honored, but I was definitely intimidated.”

Erivo was approached about “Harriet” while she was in the midst of her Tony-winning turn in the Broadway production of “The Color Purple.”

“I was in the midst of telling another wonderful story about another woman of color that meant a lot to me,” she said. “I think in doing that show I realized that that’s really what I want to do: keep telling stories about women of color who were full and rounded.”

We’re just arriving at a point now where you can have a black female protagonist in a period piece. I think that was a hard sell for people.

— “Harriet” director Kasi Lemmons

Considering Hollywood’s infatuation with biopics, it’s surprising that a story about Tubman took so long to be told.

“We’re just arriving at a point now where you can have a black female protagonist in a period piece,” Lemmons said. “I think that was a hard sell for people; they still hadn’t arrived there yet.”

Erivo added: “I think the world that we live in right now, we’ve constantly been told that we can’t do things, that we’re not allowed in certain spaces, that we have no agency. In 2019, that’s not really changed. We’ve masked over a lot of things to make it easier to swallow, but really and truly, we’re still not paid equally, we’re still not getting enough [opportunities] in the workplace, we’re barely seen on screen. And I think it’s inspiring to have this new piece of work to show that through the ages black women have been changing the world.”

In addition to climbing cliffs and performing stunts on horseback, Erivo was required in another scene to cross a river at night with water temperatures dipping below -30 degrees.

“I was awash in concern,” Lemmons said. “There’s a point at which you’re pushing people and then there’s a point where it’s like, ‘OK, don’t die. We have more to shoot and I need you.’”

When it wasn’t the physical stunts pushing the diminutive star to her limits, it was the intense emotional work.

“There would be days where we would live in the most emotional parts of her, like heartbreak,” Erivo said. “That was always really tough because your body doesn’t realize that it’s not real; it’s like you trick your body into believing where you are. We would do [those scenes] block by block, almost. So I would spend a day feeling [distraught], and it physically hurts. The day we were filming the bit about her sister, I begged, ‘Please, I can’t do it anymore. It hurts too much.’”

Nailing Harriet’s singing voice presented another unique challenge. “I knew Harriet’s voice sounded different from Cynthia’s,” Lemmons said. “And she was like, ‘Yeah, she doesn’t sound like me.’ So that was an interesting conversation. Like, ‘Where is her voice?’”

“It’s strange, but I think of a voice as a line, right down the middle,” Erivo said. “It doesn’t end anywhere. So for me, it’s like, ‘What does it sound like if I use my voice from my solar plexus and my gut? What does it sound like as opposed to sending it from [higher up]?’ It was about finding her voice and marrying that to the image I saw of her. Like I knew that she wasn’t a soprano, so she had to be either an alto or a mezzo.”

Although the film begins with Tubman in slavery and takes place largely before the Civil War, Lemmons rejects the idea that the story is a slave narrative. “It’s a freedom story,” she clarified. “It’s about what a person is willing to go through for freedom and to liberate others.”

Lemmons spent seven months researching Tubman and mapping her story into a series of outlines.

“My first outlines were enormous,” she said. “And the producers would be like, ‘Kasi ...’”

It was important to the director that the story not be just a basic rehashing of the events of Tubman’s life.

“I wanted to bring the complexity,” she said. “So it’s not just people down South picking cotton. That was something different. This was horrible, but it was Maryland [as opposed to the Deep South], and it was an interesting community of freed and enslaved African Americans living side by side and intermingling.

“I really wanted to bring her into the script that they had,” she added. “I wanted to talk about her family, I wanted to just find her. And she became very vivid to me through the research. Incredibly vivid, like I could see her face. And that’s when I felt good [about the script], when I could see her and feel her and she was real to me.”

In addition to doing her own research, Erivo worked with a dialect coach to perfect a 19th century Maryland accent along with training physically for the stunts.

I wanted to make sure that my mind was ready for it because I knew that it was going to be an emotional rollercoaster. I wanted to be strong enough...

— Cynthia Erivo on preparing to play Harriet Tubman

“I wanted to do my own stunts, so I was working with my body to make sure that it was prepared,” she said. “And really lots of meditative work. I wanted to also make sure that my mind was ready for it because I knew that it was going to be an emotional roller coaster. I wanted to be strong enough and available to allow that to happen.”

Despite the tough subject matter, Lemmons says the atmosphere on set was light and familial.

“Part of directing is creating a safe space for people to work,” she said. “But also in casting people who are good people. I talked to Joe [Alwyn, who plays slave owner Gideon Brodess] a long time before I cast him.”

“Joe was always worried,” Erivo said. “That one scene by the tree, he was like, ‘I don’t want to hurt you, are you sure?’ I was like, ‘We’re fine. You cannot hurt me. I am going to be fine.’ He was so considerate. Throughout all of it I think it took as much out of him as it did out of me. Because he was on high alert the entire time about me and where I was and my feelings.”

The ultimate goal was bringing to life a historical figure who is often studied but rarely examined in depth. One of the things Lemmons was surprised to learn in her research was that Tubman experienced fainting spells, which she believed connected her to God.

“I thought it was really interesting that she had seizures,” Lemmons said. “Her friends, her contemporaries said, ‘I don’t know if we believe it, but she believes it so hard and we can’t explain any other way how she survived.’ So my feeling is that if God wasn’t talking to her, then she had killer instincts.”

“I felt like it was a really practical thing for her,” Erivo said. “I feel like that’s how she was able to maneuver through her life. It was how she was able to make decisions: She would talk to God.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.