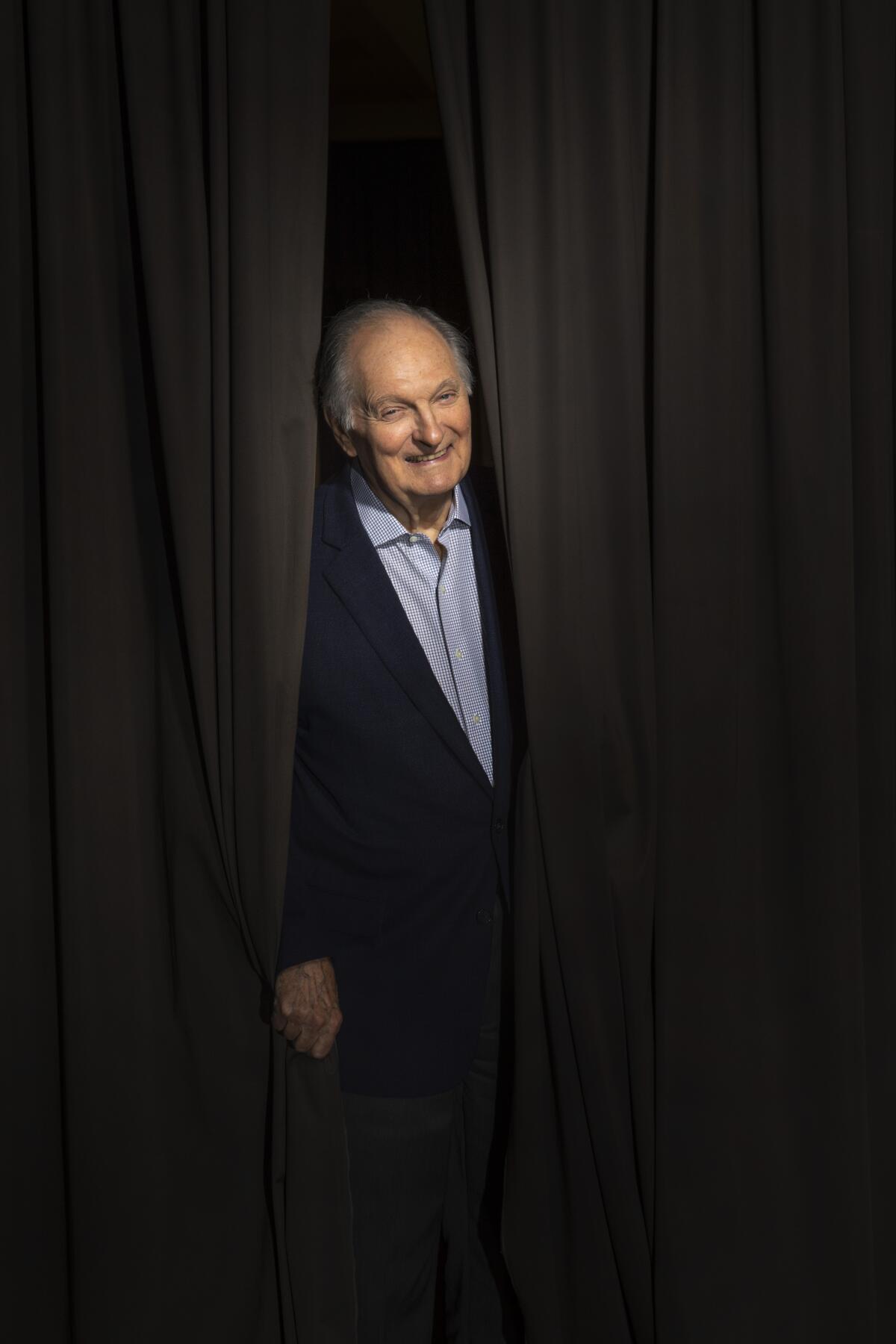

How Alan Alda almost died. And why ‘Marriage Story’ and other projects are a bonus

Alan Alda probably expected that, after playing Bert, a sensitive, world-weary divorce attorney in Noah Baumbach’s “Marriage Story,” he would be asked what makes a good marriage. After all, he and his photographer-writer wife, Arlene Weiss, have been wed for 62 years — practically a miracle in an industry in which relationships rarely last a presidential term. So when the subject comes up, the 83-year-old actor has a patented response.

“My wife says the secret to a long marriage is a short memory,” quips Alda, relaxing at the Annex at the Landmark. But after delivering his pithy punch line, he considers the question a little more deeply. “Just respect for the other person,” he says. “That’s kind of a boring answer — I like hers because it’s funny. Somebody asked me yesterday, ‘You’re in this movie about divorce, have you ever considered divorce?’ I said, ‘No, but my wife has considered murder.’”

That combination of seriousness and wry humor is at the heart of “Marriage Story,” which watches theater director Charlie (Adam Driver) and actress Nicole (Scarlett Johansson) end their marriage. Alda is the seen-it-all lawyer representing Charlie — Bert’s gone through a few divorces himself — but if you ask this multitasking actor, author, activist and podcast host what drew him to the material, he doesn’t have profound insights to offer. That’s not the way he works.

With his new film “Marriage Story,” writer-director Noah Baumbach chronicles the dissolution of a relationship.

“I loved the writing and that’s what always attracts me,” Alda says. “Some actors think about the character, but I don’t spend much time thinking about that. I don’t like to intellectualize so much. I’m not good talking about a character in that way, because what I hope is something that can’t be put into words is communicated.”

Indeed, Alda’s performance in “Marriage Story” is all about feel. Just the look on Bert’s sad, half-smiling face is enough to clue Charlie to just how bruising the divorce process, including squabbling over child custody, is going to be. “It was all in the script,” Alda says. “I just had to get underneath what Noah had in mind when he wrote it. That was the process of discovery, even while we were shooting.”

Born Alphonso Joseph D’Abruzzo, Alda grew up in a performing family. His father, Robert Alda, started in burlesque, working his way up to Broadway and movies. Alda’s roots were in improvisation — “I really value spontaneity,” he says, “not just in my own work but when I see other people’s work” — and he’s always trusted his intuition on how to play a part. Not that there weren’t anxieties along the way: When Alda signed up for the role that launched his career, Hawkeye Pierce in “MASH,” he initially couldn’t get a bead on the sardonic wartime surgeon.

“Even after 10 days’ rehearsal, I wondered how I was going to be the guy,” Alda says. “[When] I walked out of the tin shed of the compound for the first shot, I just jumped in. There was an extra passing by playing a nurse, and I just grabbed her and gave her a hug. ‘Oh, wait, I’m Hawkeye.’”

Alda laughs at the memory. “It was the kind of thing that he would do. If he did it today, he’d get #MeToo-ed.”

That apologetic tone seems very much in keeping with Alda’s public persona of being the beloved nice guy. But since 1989’s “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” in which he portrayed a soulless television producer, Alda has tweaked that image, becoming a figure of effortless retro-hip appeal. He earned his only Oscar nomination as cutthroat Sen. Owen Brewster in “The Aviator,” and he’s been embraced by new generations of comedians, landing a plum guest role on “30 Rock” and being the object of affection for the clueless geriatrics in Nick Kroll and John Mulaney’s Broadway smash, “Oh, Hello.” And his podcast “Clear+Vivid” has garnered an impressive array of guests: scientists, musicians, economists. And Conan O’Brien.

Nothing has slowed Alda — not even his announcement last year that he has Parkinson’s. In “Marriage Story,” Bert’s defeated air has a little more poignancy simply because of the slight tremor occasionally noticeable in Alda’s hand. “I wanted Noah to know that I had a tremor and he could cut around it if he wanted to,” says Alda, who has been vocal about removing the stigma surrounding the condition. He has no desire to retire from acting. “Sometimes I think of Lionel Barrymore, who acted for 10, 15 years toward the end of his career in a wheelchair. He played a variety of people — they all sat in a wheelchair, and everybody accepted it.”

Noah Baumbach pulls from life -- his and others’ -- for the highs and lows of the Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson relationship in ‘Marriage Story.’

Alda’s seemingly boundless energy partly stems from a wake-up call he received 16 years ago — a cosmic reminder to appreciate life. While in Chile for a segment for the PBS program he hosted, “Scientific American Frontiers,” he became frighteningly ill, requiring emergency surgery for an intestinal blockage. “I was about two hours from dying,” he says. “One of the great gifts I got from that was to realize I might not wake up from the operation — and to realize I wasn’t scared about that. Before that I had not liked the idea of dying. And now I know I’m going to die.” Still, he says, with a chuckle, “Waking up alive is a really nice thing.”

He sounds untroubled, enjoying this extended golden age during his golden years. “Every once in a while, I get to do something that’s really, really fine work, like this movie or Scorsese’s movie,” he says. “My whole life is like an improvisation — I don’t know what’s going to come in front of me next. If I just keep at it, probably more good things will come. [After Chile] all of this is a bonus for me. I don’t know how much more of a bonus I’ve got left. But I’m really looking forward to it.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.