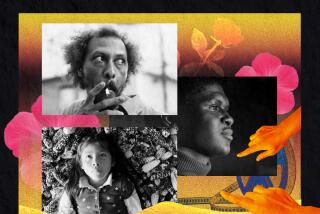

Director Ladj Ly on his incendiary Oscar-nominated debut ‘Les Misérables’

- Share via

Readers of classic literature know Montfermeil as the Parisian suburb that partly inspired Victor Hugo‘s 1862 novel “Les Misérables.” To French filmmaker Ladj Ly, it’s the neighborhood he grew up in and still proudly calls home — a banlieue where vibrant communities of largely immigrant and poor residents of color persist in an acutely modern state of despair.

“It was more than 150 years ago that Victor Hugo wrote that novel there, and you can see that misery is still present in the same place today,” said Ly during a recent stop in Los Angeles, discussing his Oscar-nominated and Cannes jury prize-winner through a translator. “Misery is still the same. The only things that changed, maybe, are that the people are more up to date and the color of their skin.”

Borrowing Hugo’s title for his narrative feature directorial debut, nominated in the international feature (formerly foreign language feature) category at this year’s Academy Awards, Ly crafts a taut drama set in modern-day Montfermeil, where poverty and unrest threaten to give way to a violent new revolution. Ly’s “Les Misérables” is now playing in select theaters via Amazon’s film division and will stream on the service later.

It was more than 150 years ago that Victor Hugo wrote that novel there, and you can see that misery is still present in the same place today.

— “Les Misérables” director Ladj Ly

Set in the wake of France’s unifying 2018 World Cup victory, Ly’s film rides along with newly transferred policeman Stéphane (Damien Bonnard) on his first day learning the ropes from bigoted cop Chris (Alexis Manenti, who co-scripted the film with Ly and Giordano Gederlini). Joined by Gwada (Djibril Zonga), Chris’ partner who grew up in the projects they now patrol, Stéphane observes how they implement a combination of negotiation tactics and brute intimidation upon the citizens of Montfermeil.

Years of overpolicing, underemployment and government neglect have left their mark, yet peace teeters tenuously among the rival factions, religions and dozens of nationalities who share the concrete blocks. Young boys play soccer and roam streets dotted with high-rises, but not all have homes to return to. Then an unusual theft, followed by a brutal incident and escalating tensions, threatens to plunge the whole neighborhood into chaos.

Through it all, Ly aims to humanize, rather than demonize, all of his characters. Instead of pointing fingers, he says he blames the system that has left its people desperate and pitted against one another.

“The movie’s called ‘Les Misérables,’ and the people in it are having a hard time,” said Ly. “It’s not only the inhabitants of the projects. It’s also the cops. It was important not to put judgment or take one side or the other and to make everyone human. Everyone is a part of humanity, whether they are good or bad.”

The neighborhood is a tinder box on the verge of exploding due to entrenched systemic rot, and the film is very intentionally, on Ly’s part, a call for action. “I made it mostly for the politicians because they are responsible for this situation that they’ve left to rot for about 40 years,” said Ly, who adapted “Les Misérables” from his own short film of the same name and based many of its events and characters on his own life.

A major source of inspiration were the 2005 Paris riots that erupted after the deaths of two black teenagers in neighboring Clichy-sous-Bois. Ly had been making films since age 17. When the riots broke out, triggering weeks of violent antiauthoritarian unrest among French youth, he grabbed his camera and started documenting.

The resulting film, a vérité document titled “365 Days in Clichy-Montfermeil,” was released for free online via Kourtrajmé, the filmmaking collective founded by French filmmakers Kim Chapiron, Toumani Sangaré and Romain Gavras.

“It was really important to me to show what was going on in my neighborhood because I grew up there, I’m part of it,” said Ly, who also helped open a film school in the area for aspiring filmmakers. “There was an enormous gap between the [media depiction] and what was actually happening, and I wanted to show my perspective of what was going on there.”

Making “Les Misérables” from an ambitious script with a limited budget, however, took much more effort in a more traditional landscape. “From the beginning we knew it was going to be harder to finance this movie in France because you have this topic of the banlieue; people just want to see a movie with a hopeful message, not movies that are so strong in what they propose,” said Christophe Barral, a producer on the film alongside Toufik Ayadi.

Rather than compromise to make a more commercial film — a work true to Ly’s confrontational ending, with lesser-known actors they loved in the lead roles — the filmmakers opted to shoot the project for 1.4 million euros, half their original budget. They whittled shooting days, saved on set costs and scored a Ladj Ly special by filming in his hometown, where he could recruit locals he already knew to be part of the film.

“Ladj is the son of Montfermeil,” said Barral. “When you work there everyone says, ‘Hi, Ladj, how are you doing?’ So he could do basically whatever he wants.” To save money on a crucial final sequence in which characters face off in a melee inside a residential housing building, they filmed it in Ly’s own building.

“We knocked on every door and said, ‘For two days we’re going to make a bit of noise, we’re sorry,’ and we asked the kids to write on the walls, and at the end of the shoot we repainted it,” he said. “This was what we did, taking all the truth we could get from this neighborhood and making it into fiction.”

The movie’s called ‘Les Misérables,’ and the people in it are having a hard time... It was important not to put judgment or take one side or the other and to make everyone human. Everyone is a part of humanity, whether they are good or bad.

— Ladj Ly

Ly’s love for Montfermeil fueled “Les Misérables” in several ways, the producer added. “A lot of people could have a bit of success and leave Montfermeil, but Ladj says, ‘I will never leave. This is my home,’” he said. “Lots of people could have an apartment in Paris, but he’s the kind of guy who says, ‘No — I’m staying there.’”

The son of Malian immigrants, Ly recalls how he based many events and characters from the film on real life. One such incident involving a missing lion cub and its irate owners actually happened to his friend. He paused to pull up a photo of it on his phone, a note of amusement in his voice.

“I was 18 years old... It had been stolen by a buddy of mine,” he said of the cub, which was returned before long. What possessed them to steal a lion in the first place? “One of my buddies joked that maybe we should grow him — in case the cops become too brutal and give us too hard of a time, we can use it.”

Another moment inspired by real life unfolds when a quiet boy named Buzz, played by Ly’s own teenaged son Al-Hassan Ly, sends his remote-controlled drone soaring into the skies above his tiny patch of concrete only to accidentally capture a shocking incident that puts him on the entire neighborhood’s radar.

In Ladj Ly’s contemporary “Les Misérables,” a drone captures an out-of-control arrest by an anti-crime unit amid tensions in the projects in Paris.

In Ly’s “Les Misérables” it’s not a street urchin called Gavroche but a neglected immigrant kid named Issa (Issa Perica) whose mounting isolation comes piercingly into view. “It’s really hard to live when as a kid you find out and feel that you’ve been abandoned. Because they’ve been abandoned by the local authorities,” he said.

Even after premiering the film at Cannes and winning its jury prize, Ly’s quest to get “Les Misérables” seen by France’s highest officers took considerable effort. He invited French President Emmanuel Macron to visit Montfermeil for a special screening, but Macron declined. So he sent him a DVD. “He watched it and was very touched by the story and the movie, and he has people trying to figure out a way to help these neighborhoods,” reported Ly.

A great deal of other French moviegoers have seen “Les Misérables,” which will compete against South Korea’s “Parasite,” Spain’s “Pain and Glory,” Poland’s “Corpus Christi” and North Macedonia’s “Honeyland” at the 92nd Oscars on Feb. 9.

Ted Hope, co-head of Amazon’s movies division, saw potential for American audiences to connect to the sociopolitical themes of the film.

“I think similar to the neighborhood of Montfermeil, we are also seeing racial and political divisions in the U.S.,” wrote Hope via email, citing comparisons of “Les Misérables” to films like “Training Day.” “But beyond anything else this is a gripping, exciting, action-packed movie that wide audiences will immediately be drawn into.”

At home in France the film has sold nearly 2 million tickets, approaching the admissions bar set by Mathieu Kassovitz’s spiritual predecessor “La Haine” in 1995.

“It’s perfect,” said Ly. “Most important is that the message is going through and that the movie is seen by as many people as possible.”

Reacting to his first Oscar nomination on Monday, Ly spoke of making change through cinema. “We are all Misérables in the sense that we are all immigrants,” he said in a statement. “But we can all do the revolution, me I am doing it with my camera. I believe in the power of cinema as a tool to challenge the politics and even sometimes to inspire revolution and above all bring real lasting changes.”

Even seeing “Les Misérables” shortlisted for the Oscars meant a great deal to Ly. “It’s a really strong signal and really important,” he said before the nominations announcement. “It’s a movie that represents France. I’m really proud. And I represent French cinema now.”

That alone is a huge deal for a filmmaker who grew up without French cinematic heroes he felt he could relate to. “I didn’t recognize myself in the movies,” said Ly, who will resume work developing his next two projects — after the Oscars. “I had to become my own.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.