Why the creators of ‘Persuasion’ put a contemporary spin on Jane Austen’s classic

- Share via

London — In “Persuasion,” a new adaptation of Jane Austen’s final novel made for Netflix, protagonist Anne Elliot speaks directly to the camera, addressing the audience like an old friend. As she muses on her relationship with former flame Capt. Frederick Wentworth, Anne bemoans that they are now “worse than exes, we’re friends.” Austen, of course, didn’t write that in her 1817 novel, but the sentiment resonates with the sense of longing the English author evoked.

For screenwriters Ron Bass and Alice Victoria Winslow, who collaborated on the adaptation, the goal wasn’t to alter Austen’s intention or story. Instead, the writers wanted to bring a contemporary tone into a classic tale.

“I’ve loved Jane Austen my whole life, and ‘Persuasion’ has always been my favorite novel,” Winslow says. “I relate so strongly to the book and I relate so strongly to Anne that I’m constantly drawing connections between my life and Anne’s. So it felt pretty natural to give voice to a modern sensibility through these characters.”

British theater director Carrie Cracknell retained the period setting of the story, as well as most of its historical accuracy. The sets, costumes and background details will be familiar to fans of the novel and prior adaptations, but the way in which the story is told, as well as some of the language, has been modernized.

“The film is set pretty faithfully in the sumptuous Regency period, but the physical behaviors, attitudes and elements of the aesthetic also lean towards now,” Cracknell notes. “We have simplified some of the lines, and taken away some of the fuss of period trimmings, to make the characters and the worlds feel more alive and accessible.”

The goal of these noticeable changes is to welcome a fresh batch of viewers into Austen’s world. The themes of regret and fear of your life running away from you resonate as much now as they did in the early 19th century.

“I hope we draw in new, younger audiences who perhaps know very little about Jane Austen,” the director explains, “and that a whole new generation will watch the adaptation, and then be drawn to read and fall in love with the book.”

Dakota Johnson’s TeaTime Pictures will unveil “Am I OK?” and “Cha Cha Real Smooth” at this year’s virtual Sundance Film Festival.

While the filmmakers are aware of the potential backlash over remixing a classic novel, every change was made with Austen in mind.

“Her words do speak to [a] contemporary audience in many, many ways, just not necessarily every way,” says Bass, who is working on similar updates of “Pride and Prejudice” and “Sense and Sensibility.” “I promise you that everyone involved in this adores Jane Austen and adores her work.”

“We’re all big fans of the book and pretty reverent to it in the ways we could be,” Winslow adds. “We tried to make sure we were capturing the sensibility in all moments, even when some of the language changed.… I’m really hopeful that when people watch it, they’ll see how much love for the material is actually within the film.”

Here, the filmmakers discuss how and why they updated “Persuasion” for the 21st century.

Breaking the fourth wall

While the novel is written in third person, with Austen playing the part of narrator, Cracknell’s “Persuasion” sees Anne (Dakota Johnson) speaking directly to the viewer. It’s a similar sensibility to “Fleabag” or “Enola Holmes,” where a protagonist breaks the fourth wall to explain her feelings with immediacy. Bass was determined not to use voice-over narration, which can feel too reflective, and the goal was to “disappear the distance” between the audience and the heroine.

“What happens in prose is what happens within people,” Bass explains. “What happens in film, unfortunately, is what happens between people. Jane Austen [creates] this wonderful inner life for these people, and we don’t know what it is. In direct address, when Dakota turns to you and makes you her best friend and can tell you anything she wants to say, [we are] tapping into that inner life. She makes that distance zero when she talks to you.”

He adds, “She’s not talking as a narrator. She’s talking as a girlfriend, as your best friend. So it’s an in-character conversation; it’s not a retrospective analysis.”

In the story, Anne isn’t afforded much freedom. She’s forced to give up Wentworth, the love of her life, because he isn’t wealthy. She lives in a time when women don’t have many options. But by speaking to the camera, this version of Anne takes the helm.

“I felt like it was a way of giving Anne agency as a character because part of agency is being able to tell your own story [and] being in control of your narrative,” Winslow notes. “Anne may be trapped in a world in which she doesn’t have very many personal rights or, frankly, much control over her life, but can we give her control over her voice? Can we give her control over her story?”

Modernizing the language

The most glaring alteration to “Persuasion” is the inclusion of modern-day language, including meme-ready Gen Z speak. A character quips, “It’s often said that if you’re a five in London, you’re a 10 in Bath” when the Elliot family is forced to relocate to Bath, England. Elsewhere, Anne expresses that her favorite way to dance is alone in her room “with a bottle of red.” The protagonist also describes a stack of sheet music, given to her by her lost love Wentworth (Cosmo Jarvis), as a “playlist he made me.” While these lines are memorable, the screenwriters endeavored not to let them overwhelm the dialogue.

“The script went through many stages,” Winslow recalls. “And I would say there were some [versions] that were much more toeing the line in terms of contemporary language. It was a constant negotiation of what we thought was fun, what would be funny, what would take people out too much. I think we hit a medium, actually, in that process. We came back to a middle zone.”

“We weren’t planning ‘Here’s how many modern things we’re going to do,’” Bass adds. “We just said, ‘Let’s be sure we don’t do a lot of them.’ Something like the exes line — she would never have known that phrase, of course, but does it ring true? And doesn’t it make you feel, ‘Wow, she’s in a place where I could see myself being’?”

The new lines are intended to be playful and funny — just as Austen was in her own writing.

“We wanted to capture that spirit of play in our engagement with the material,” Winslow explains. “And I think a way of doing that was to be playful with anachronism and to be playful with language. For me, it was a way of capturing her sensibility in a new way while also bringing modern audiences in a little more.”

The screenwriters also modernized some of the descriptive cues in the script, occasionally referencing contemporary ideas or people. For Kellynch Hall, majestic home of the Elliot family, the script noted that a particular wall, as Winslow describes it, “looks like Justin Bieber’s Instagram account if it were 1812 and the Regency oil painting filter were on.”

“There was something right from the get-go of bringing this world to our own and finding where they matched,” Winslow explains. “Because her father is just hilarious. He’s a classic narcissist.”

Elsewhere in the film, as Anne recounts Wentworth’s feats in the Navy, the screenwriters evoked social media. “Those are described as looking similar to like a Facebook news feed,” says Winslow. “There are little hints of that elsewhere in the script as well.”

Retaining key elements

While Bass and Winslow wanted to evolve some of the language and the story’s delivery, there were certain aspects of Austen’s work they didn’t mess with. Certain lines were taken word for word from the novel. An important letter that is sent toward the end of the film is almost verbatim to what appears in the book.

“There’s an enormous amount of direct-from-Jane dialogue,” Bass confirms. “And then there’s a lot of lines of hers that are very slightly parallel. So there were some lines that are new dialogue that we wrote, but most of it was written 200 years ago.”

The plot, too, is faithful to the novel. The writers cut one secondary character, but generally what happens in “Persuasion” — and whom it happens to — also happens in the film.

“I was pretty dead set on following the plot,” Winslow says. “I did not want to structurally alter the story. I don’t want to give spoilers, but there’s like a slight alteration in timing in terms of when information is delivered towards the end. But it was really important to me not to alter the structure of the story. The character of Mrs. Smith went, but that was more just a necessity of time and space.”

Diversifying the cast

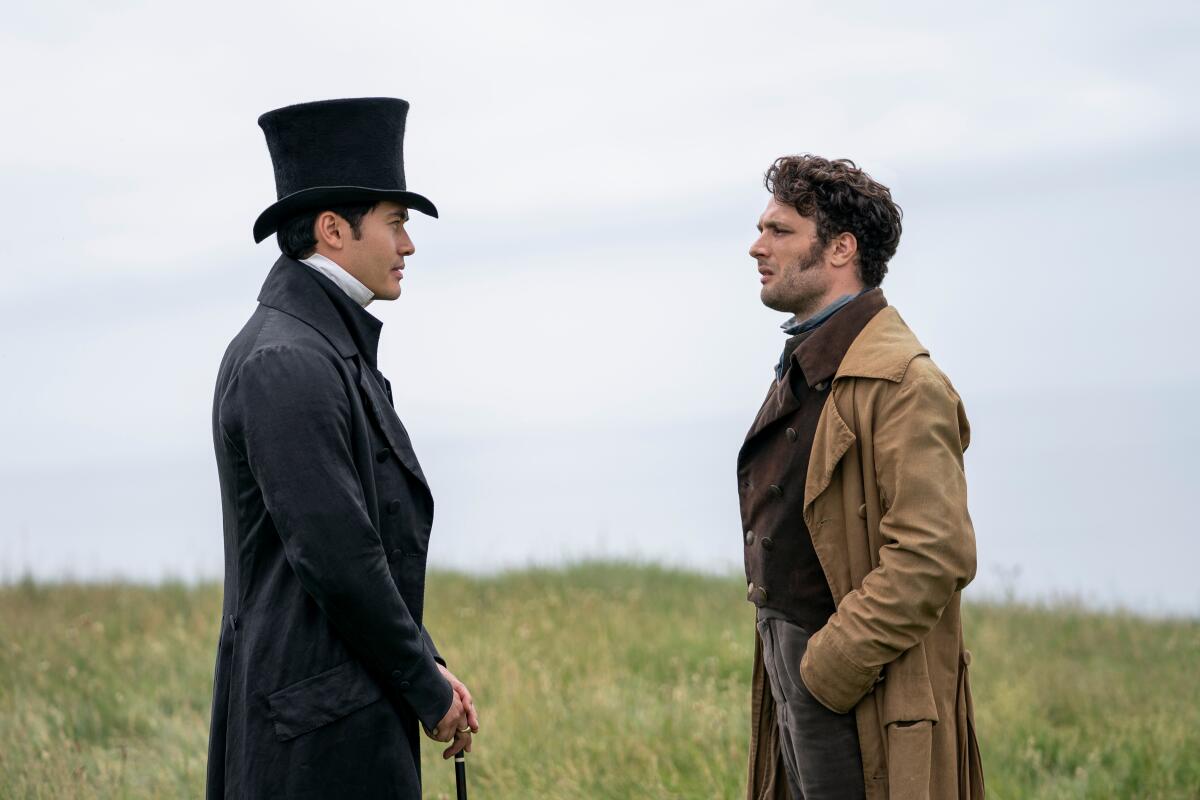

While England in 1817 wasn’t the most diverse place, this onscreen version of “Persuasion” was cast more inclusively. Henry Golding plays William Elliot, Anne’s cousin, and Nikki Amuka-Bird embodies the high-society Lady Russell. Anne’s sister Mary (Mia McKenna-Bruce) is married to Charles Musgrove (Ben Bailey Smith), who is a Black man. Bass and Winslow didn’t write specific casting notes into the script, but Bass says the array of actors suits the story.

“When the suggestion came up, my reaction was ‘Sure,’” Bass recalls. “Because it’s not an issue in her time. Her time wasn’t about racial issues. Because, of course, there weren’t other races that were involved in the world that she was dealing with, so the idea of colorblind casting [worked]. Henry Golding could play Mr. Elliot because it doesn’t really matter. And Nikki could play Lady Russell. There’s no reason not to.”

Ultimately, Cracknell hopes the ensemble will encourage more viewers to find their way into what can be a universal story.

“I wanted the widest possible audience to see themselves in this film,” Cracknell says. “Jane Austen is a cornerstone of British literary culture, and I wanted a really diverse group of people to be able to access this story and feel drawn into it.”

Dakota Johnson plays Anne Elliot in an ill-advisedly “Fleabag” key in this flat-footed adaptation of one of Austen’s finest works.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.