Queer history has been ‘deliberately destroyed.’ These filmmakers aim to fix it

- Share via

Kristen Lovell had a straightforward goal when crafting “The Stroll.” As she puts it in the HBO documentary, co-directed with Zackary Drucker, “I wanted to make people understand the reality of our lives through storytelling.”

The lives she’s referring to are those of trans women who for decades walked up and down the titular “stroll.” Located in a pre-gentrified Meatpacking District near 14th Street in New York City, the area was a safe haven for trans women like Lovell, many of whom turned to sex work as the only viable route to survival.

“The Stroll,” premiering Wednesday on HBO and Max, is anchored by a number of poignant testimonials from generations of trans women who once walked and worked that infamous strip. But the doc is most impactful for the way it reuses photographs and archival images from news broadcasts and documentaries, reframing how the history of the stroll — and queer history more broadly — can and should be told.

Lovell and Drucker reframe sensationalized images of trans sex workers shot for the nightly news in a way that reclaims them for the very community they’re honoring. The project, which also uses cut-out animation and shuttles handily between grainy vintage footage of the stroll and its sanitized 21st century visage, filled with high-end designer stores and glittery art galleries, is a testament to how such an endeavor requires a keen understanding of its urgency.

“That’s something Kristen and I have in common,” Drucker says: “We are both seekers. We are both looking for the ephemeral traces of our predecessors and trying to locate ourselves in that.”

“The very best queer history doesn’t just write up the histories of LGBTQI+ people,” says Jennifer V. Evans, author of “The Queer Art of History.” “It questions why certain lives and ways of being in the world have come to take up space in the public imagination and history writing in general.”

To commemorate next year’s 40th edition of the Sundance Film Festival, we’re spending 12 months looking at the lives of 7 members of this year’s class.

Projects that aim to excavate such histories necessarily require examining how and to what end such stories have been told. “Queer history puts an emphasis on the way historians make meaning itself in how they piece together traces of the past,” Evans adds.

For Lovell and Drucker, “The Stroll” is an instantiation of their own interest in making queer and, specifically, trans histories visible. It is, above all else, a project driven by oral accounts. As Drucker says, “This is a history that I have experienced as passed down through stories with my elders. Coming into trans life in the early 2000s, I really couldn’t find myself in any organized realm of history in many books.”

Lovell, who first learned about those who came before her directly from gay rights pioneers like Bob Kohler and Sylvia Rivera, adds that as a homeless trans woman, she was “thrust into the middle of this history.” She watched as Manhattan’s West Side piers and later the stroll were slowly destroyed as spaces for queer and trans youth who had not just survived but also thrived there. To tell the story of the stroll, then, meant revisiting how such spaces had been presented to those outside the LGBTQ+ community.

Research for “The Stroll” uncovered a slew of materials from the unlikeliest of places and at times required recontextualizing bigoted depictions, given that the end goal was a compassionate and intergenerational chronicle of New York City trans history.

“CNN had a bunch of stuff,” Lovell recalls. “Even HBO had a bunch of stuff. More photographers and photographs started to emerge. We ended up getting more than we were looking for. I even learned so much more in reclaiming the footage we’d seen. I mean, we’ve seen all of these docs and things about trans people and they frame trans women in a very specific way. So we took that for representation in general, even if they’re in a janky film, and repurpose it to tell the real story of what it was like to be out there. Not just the drug addiction. Not just the violence. There was joy there, even when we were in the bullpen heckling the cops.”

This awareness that the way we tell history shapes what is being told is at the center of a wave of contemporary nonfiction projects that, like “The Stroll,” aim to reclaim oft-forgotten stories about the LGBTQ+ community for contemporary audiences. And they do so by using overlooked materials like those Lovell and Drucker so lovingly reanimate in their documentary, which won a special jury award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival for clarity of vision.

For L.A.’s queer community, competing Pride festivals aren’t about infighting. They’re oases from a nationwide conservative attack on LGBTQ+ rights.

Sometimes those traces are quite unassuming. In “All Man: The International Male Story,” filmmakers Bryan Darling and Jesse Finley Reed use the International Male fashion catalog as a springboard to tell a larger story — about masculinity, American entrepreneurship and the toll the AIDS crisis had on the merry band of creators who launched the mail-order business, whose queer aesthetics and erotic images fueled countless cultural and sexual awakenings. Excavating such a seemingly banal subject, “All Man” reminds viewers that historical archives exist even in the most mundane of spaces. And that queer folks themselves have much to learn from those traces.

For Darling and Finley Reed, their interest in these stories is simple. “The reason why I’ve worked on so many queer projects in my professional life has been, in a way, to understand my own identity and the context for that,” Darling says.

Yet there’s nothing simple about reassembling such histories. After all, the lives of LGBTQ+ folks have historically been reduced to criminal or clinical archives, to spaces and ledgers and documents often designed to oppress, if not outright erase, their own existence.

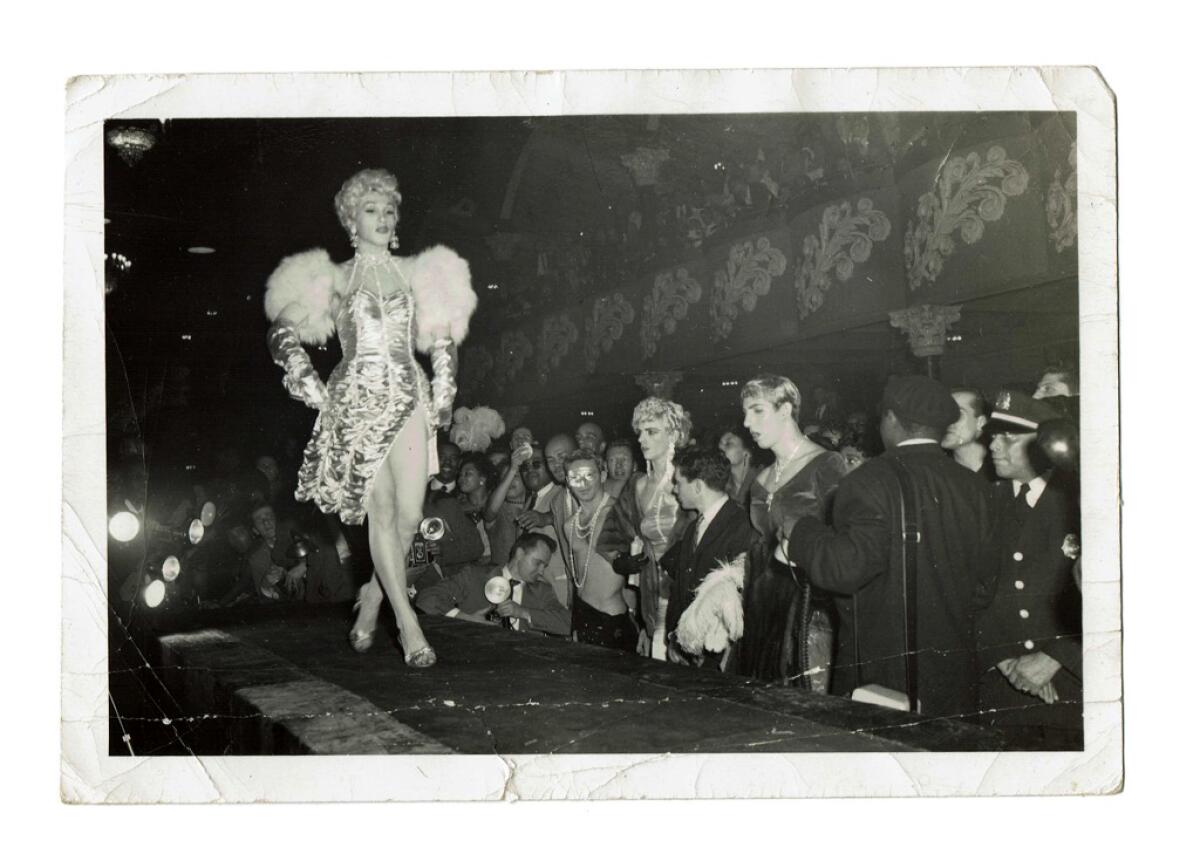

In the aptly titled 2020 documentary “P.S. Burn This Letter Please,” for instance, filmmakers Jennifer Tiexiera and Michael Seligman turned a treasure trove of found letters among New York City drag queens in the 1950s into a celebration of pre-Stonewall queer history — a history that would have been lost had that correspondence been destroyed upon receipt as instructed.

As Tiexiera puts it when discussing why such projects feel doubly difficult to produce, “The cards are stacked against you. Not only is it hard to find, it’s like a lot of it was either deliberately destroyed or mislabeled or hidden. It’s not just like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna have to look for this.’ It’s, ‘I’m gonna have to look for something that somebody tried to destroy or hide.’”

The team behind “P.S.” spent years tracking down the letter writers (many of whom had used pseudonyms and/or drag names to sign their letters) and months more persuading them to share their experiences on camera. For Seligman, the film was an opportunity to strike back against reductive ideas of what life for out queer folk was like before the age of gay liberation.

Letters found after the death of William Morris agent Ed Limato led to the documentary “P.S. Burn This Letter Please” and untold stories of queer life.

“History is such an empowering thing. Having an understanding of where you come from, and that we do have ancestors that we can be proud of — that we do stand on the shoulder pads of the communities that came before — is such a powerful thing,” he says. “And it’s a living thing. So this isn’t just telling stories of a long time ago. This is telling our current story.”

“Framing Agnes,” Chase Joynt’s 2022 genre-breaking nonfiction film about the pioneering, pseudonymized trans woman who participated in sociologist Harold Garfinkel’s gender health research at UCLA in the 1960s, goes one step further. Starring “The Stroll’s” Drucker as its eponymous protagonist, Joynt’s imaginative project is intent on both recontextualizing Agnes as a prominent trans figure and conceptualizing queer history as a bridge between the then and the now, an ongoing intergenerational effort.

This isn’t just queer history. It’s queering history, Joynt says: crafting stories of the past that work “against the dominant narrative or mainstream interpretation.” For instance, “Framing Agnes” revisits decades-old clinical cases by staging them as black-and-white talk-show segments. Joynt’s gamble helps reveal the twinned ways in which trans histories have been archived (the dry language of medicine; the scandalous imagery of daytime TV), yet he refuses to see those as static, embalmed in a long-ago past.

“I think that we over-pressurize archives to tell us something about ourselves or our histories,” Joynt says. “And so what if we let the archive be incomplete? What if we let the archive be a trace? What if we understand the archive to not necessarily be telling us the truth of anyone or anything?”

Such a provocative question is what anchors “Framing Agnes.” By recruiting Zucker and a number of other trans performers (including Angelica Ross, Jen Richards and Silas Howard) to bring this clinical archive to life, Joynt places queer history in conversation with the present moment.

Similarly, a piece of reimagined and reframed history like “The Stroll” is possible precisely because traces and tales of those who walked those streets remain — they have been kept alive by elders for whom it is not history but lived experience. Lovell, who had bits and pieces of video and photography about the stroll for years, credits the film’s archival producer, Olivia Streisand, for finding a wealth of images that she and Drucker could use to bring this environment to life.

“Truly, this is an archival documentary,” Drucker notes. “This [story] exists primarily in the archive. And that’s the magic of filmmaking; the people who no longer exist can speak to you through time and through dimensions.”

The key, as these many projects attest, is a willingness to listen. “It’s important to make sure that everybody has their say,” Lovell acknowledges. “It just leaves the door open for so many other stories to come out. Because it’s not just the one. There’s always many.”

‘The Stroll’

Where: HBO

When: 9 p.m. Wednesday

Streaming: Max, anytime

Rating: TV-MA (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 17)

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.