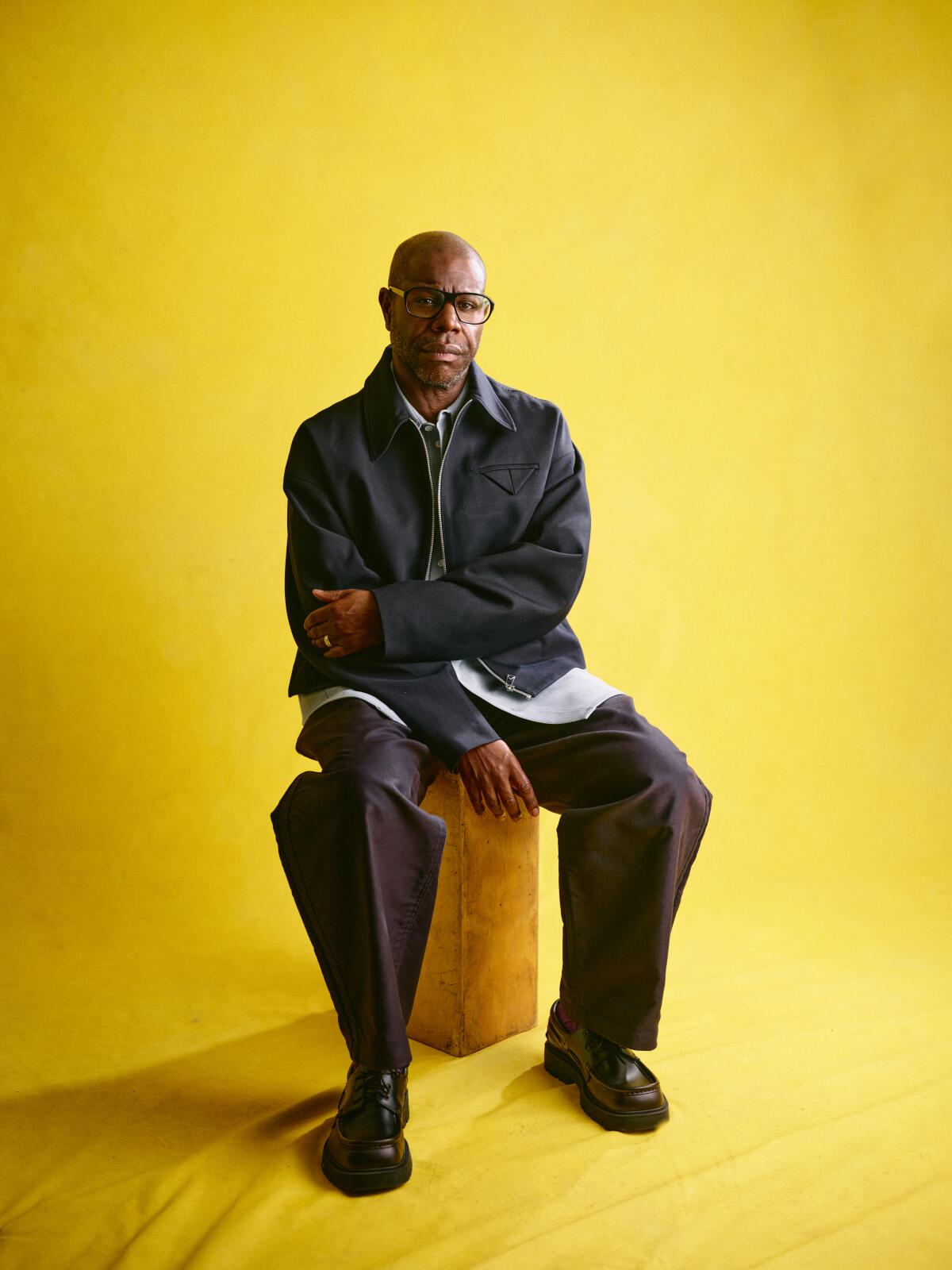

Steve McQueen on making WWII personal with ‘Blitz’: ‘It’s about us fighting ourselves’

LONDON — Steve McQueen is hopeful. It’s a viewpoint that’s admittedly discordant with what’s happening in the world, but the British director embraces a flame of optimism. The sensibility is apparent in his most recent film, “Blitz,” even though it centers on the destruction of London during the German air raids of World War II, while also conveying an undercurrent of the racial strife that lingers in the U.K. today.

McQueen, 55, is quick to rattle off a list of modern-day conflicts that have parallels to the film — in the Ukraine, the Middle East, Libya. But still he’s convinced sunnier days are ahead.

“We could have that,” the filmmaker says, sitting in a quiet room in London’s Soho Hotel during a long day of press ahead of BFI London Film Festival. He’s dressed up for the occasion in a black suit, although he slouches casually on the sofa. He speaks with a quick-fire cadence, spilling out thoughts as if his words can’t keep up with his brain. “Is it likely? I don’t know, but things could be better. One has to end on some sort of high, you know? Some kind of hope in a landscape of devastation.”

It’s why McQueen has bookended “Blitz” (in theaters Nov. 1) with a black-and-white shot of daisies, flowers that seem to represent a nostalgic ache for a better time, even if the story itself centers on England’s darkest days. The film follows a young mixed-race boy named George (Elliott Heffernan) who is shipped out of London by his mother, Rita (Saoirse Ronan), and his grandfather Gerald (Paul Weller) as part of the British government’s evacuation of children in the cities. Although Rita is desperate to keep him close, the bombardment is a constant and unnerving threat to everyone. But soon George leaps from a moving train and journeys back to London’s East End via a series of tumultuous adventures and chance meetings that forever change his understanding of both the world around him and himself.

“Often people think war is what happens in far distant places,” McQueen says. “I wanted to bring it home: This is what happened here. This movie has a real sense of urgency, unfortunately. I wanted it to be a roller-coaster ride through London during the war.”

McQueen himself was born in London, the child of West Indian immigrants, although he has also lived in Amsterdam since the late ‘90s. From a young age, the story of the Blitz was ingrained in his experience of the city and in his understanding of what it means to embody the British spirit of “keep calm and carry on.” Growing up, he remembers echoes of the bombings — missing buildings, rebuilt neighborhoods, playgrounds he frequented that had sprung up in the hollows of the explosions. Even the Royal Festival Hall, where “Blitz” had its world premiere this month during BFI London Film Festival, was constructed on the site of a massive bomb blast.

“The seeds were planted in my imagination from day one,” McQueen says. “The Blitz is all around you. It’s one of the foundations of our identity.”

It’s not an accident that all of McQueen’s films — from his Oscar-winning “12 Years a Slave” to 2008’s “Hunger” and 2011’s unnerving psychological piece “Shame” — are dramas, often featuring distressing scenes that reveal the worst in humanity. He stares directly into the void, yet somehow emerges without cynicism. He explains that growing up as a Black child he couldn’t avoid being confronted by his reality. His very existence was political and it forced him to ask questions about everything early on. In his art, he does so to appease that lingering sense of curiosity.

“I’ve made things because it was challenging and because it was rewarding and difficult and actually confrontational at the same time,” McQueen says. “I’m not going to go down the easy path. That’s just who I am and what it’s about. I’m trying to find some kind of truth, or whatever it is — I don’t know what we’re looking for or what we’re trying to do. But I know it’s interesting when you’re working in a way which is confrontational.”

It was while writing 2020’s “Small Axe,” his anthology of films about the lives of West Indian immigrants in London, that McQueen came across a photograph that brought “Blitz” to the forefront of his mind: an image of a young Black boy in an oversized coat with a large suitcase, standing on a railway platform during World War II. The unidentified boy, one of more than 800,000 children evacuated from cities in the U.K. during the war, was a striking discovery.

“Who is he? Where is he from?” McQueen asks, still gripped by the power of the stark photograph, acknowledging that Black children have rarely been part of the war narrative in England.

For McQueen, the existential story of WWII wouldn’t be about the soldiers or the front lines, nor about Winston Churchill or George Patton. It was about the women working in the munitions factories and the families surviving the bombardment every night from behind blackout curtains or in the Underground stations. It was about children faced with racism in a country purporting to fight against injustice abroad.

“I was interested in the ordinary people who had to deal with the consequences of decisions being made by the people in charge,” he says. “I was interested in George and Rita and the people around them.”

That’s also what attracted Ronan, 30, who, speaking from her home in London in September, says she didn’t “want to get involved in a World War II epic in the traditional sense.”

“The one thing that Steve said to me that really stuck in my head is, ‘These people felt like they could die tomorrow, so they were going to do what they wanted,’” Ronan says. “There was just this buzz that was fueled by fear, but also feeling probably invincible as well, because it was like, ‘F— it. What else are we going to do?’”

“Blitz” feels different from most WWII movies. It’s less reverential and more instinctual, despite its reliance on historical fact. McQueen enlisted author Joshua Levine as a historical advisor and did extensive research with the help of the Imperial War Museum and the British Library to produce an original screenplay. As young George traverses the city, the viewer glimpses many things that actually happened, including the catastrophic flooding of a Tube station being used as a shelter and the destruction of nightclub Café de Paris, later looted by a crew of thugs led by Stephen Graham’s Albert. Several characters, such as Benjamin Clementine’s air-raid warden Ife, are based on real figures.

Saoirse Ronan, already a four-time Oscar nominee at 30, crashes through a new ceiling with career-high performances in “The Outrun” and the WWII drama “Blitz.”

“When George jumped off that train, he changed the narrative that was set for him, which was very courageous,” McQueen says. “I want to amplify that for the audience — that we actually generate our own narrative.”

Experiencing the story from the perspective of a 9-year-old also served a greater purpose for the director. It underscored the human obsession with war, ultimately questioning why we destroy one another for borders or beliefs.

“First and foremost, this film is about love,” McQueen says, offering as an aside that he is sometimes embarrassed to say that. “As a child, there’s right and wrong, there’s good and bad. So at what point do we as adults compromise? At what point do we turn the blind eye? At what point did we pretend not to hear? War is bad enough, but through a child’s eyes you see the insanity of it in a greater way.”

It’s not surprising that McQueen describes his motivation as that of “observational curiosity.” As a filmmaker and a visual art, he looks intently, hoping to glean answers to questions that feel unanswerable. His prior work reverberates in “Blitz.” As the camera pulls back to reveal a smoldering, battered London, it’s hard not to notice a parallel to his 2023 short film “Grenfell,” which depicted the tragic aftermath of the 2017 deadly Grenfell Tower blaze, which resulted in 72 deaths.

“I’m interested in who are we — and what are we — within a landscape,” McQueen says of his instinct to occasionally step back. It’s a distance, he says, that “puts things in perspective.”

There’s also perspective to be found in the close-up. Actors obsessively want to collaborate with him and some, like Michael Fassbender, have returned again and again to his projects. His scripts are airtight, but McQueen always leaves space during filming for what he refers to as “magic.” It might be an unscripted moment between two actors that he captures or it might be an unexpected take where the emotion veers away from the original intent. The film, McQueen says, has to be better than the script, which means being open when “things actually happen.”

“You buy into his vision,” actor Graham says, speaking during a separate press day for “Blitz.” “He’s able to create an atmosphere for you to be able to play. And you have no fear because you can’t get it wrong, because there is no wrong, there is no right. You’re just finding what’s truthful. He’s like a great football manager. He gives you that great pep talk and then you tie your boots on and you run out there and run up and down the pitch.”

McQueen’s recent work, including “Small Axe” and “Blitz,” reflects back in order to understand where we’re headed. In doing so, the filmmaker has realized that “we’re all bloody mad,” something he says with matter-of-fact certainty. Yet somehow the process has focused him even more on love.

In his collection of five films, his most personal works to date, the director honors his family and his West Indian community in London.

“This movie is not just about us fighting the Nazis,” he says. “It’s about us fighting ourselves. And I just feel that love is the only thing worth living for and the only thing worth dying for. That’s it. There’s nothing else. Through all the madness, through the nonsense, through all the things that we go through in our daily lives, all the troubles, if we just focus on that, it would give us some kind of solace.”

Now, though, the filmmaker has turned a page. In middle age, he says, you tend to look back to know who you are, but his next film might do something else. It won’t be a comedy or an animated film, he’s pretty sure, because McQueen isn’t interested in “altering the reality of how we live.” Instead, he shows us things as they are.

“What this is doing is correcting [history] or reexamining it,” he says of his recent work. “It’s not about depicting life as some kind of dream. It’s about looking at how it actually is.”

With “Blitz,” this means showcasing the extreme highs and lows of life in London during the war with judgment, including the undeniable racism.

“What’s really great about Steve as a British filmmaker is that he doesn’t have this romantic view of the U.K.,” Ronan says. “He wants to show it warts and all. He loves it, but he also knows it’s false. A lot of people, when it comes to Britain — and they do it in America as well sometimes — will shy away from that when it comes to a big commercial movie. I think it’s very clever of him to give us a well-rounded picture of this place.”

At the premiere of “Blitz” in London, which happened to take place on McQueen’s birthday, the director invoked John Lennon’s 1971 song “Imagine.” The lyrics, he tells me, emphasize the hopefulness he feels. They also underscore the only answer he’s ever uncovered in his years of asking questions.

“The more you know, the less you know,” he says. “But the only thing that’s absolutely true is love.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.