Trying to cope with despair? Take solace in the compassion and empathy of Bill Withers and John Prine

- Share via

One came back with a hole in his arm where all the money goes; the other came back with no arm at all.

Such were the soldiers John Prine and Bill Withers wrote into existence nearly 50 years ago to illustrate the horrific toll of the Vietnam War — Prine in “Sam Stone,” about a drug-addicted veteran with “a hundred-dollar habit,” and Withers in “I Can’t Write Left-Handed,” in which the wounded narrator asks his buddy to take down a letter to his mother.

Bill Withers, known for acoustic soul hits “Lean on Me” and “Ain’t No Sunshine,” died Monday of heart complications, his family said Friday.

Both songs — the former from Prine’s self-titled 1971 debut, the latter from Withers’ 1973 “Live at Carnegie Hall” — are vivid reminders of an era when Americans were forced to weigh the value of human life against the perceived need to defend our individual freedoms. (Sound familiar?) Yet as bleak as each man’s situation seems, the empathy coursing through both tunes is ultimately reassuring; it offers hope that someday someone will understand your problems as completely as these two songwriters understand their characters’.

I’ve been thinking about that shared sense of compassion, along with some of the other ways in which the two overlap, since news broke that Withers had died from heart trouble at age 81 and that Prine, 73, had been hospitalized after falling seriously ill from COVID-19. (On Thursday, Prine’s wife, Fiona Whelan Prine, said on Twitter that her husband had pneumonia in both lungs and had been placed on a ventilator.)

The timing of this unwelcome news — amid a terrifying health crisis likely to kill more Americans than died in Vietnam — is cruel; it’s also reason to turn to their music, which feels uniquely suited to the emotional demands of just such a moment.

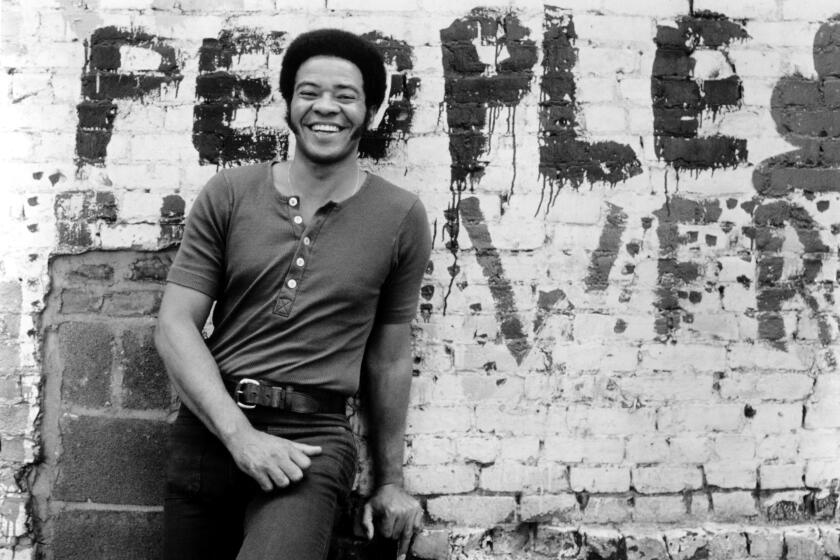

The first thing to consider about John Prine and Bill Withers is how unlikely their stardom can seem by modern standards. With family roots in the coal-mining country of Kentucky and West Virginia, both men served in the military and worked blue-collar jobs — Prine was a mailman, Withers an airplane mechanic — before busying themselves fully with music.

Nowadays we like our beginners to appear out of nowhere or to emerge from the pop-star polishing school of reality TV. But from the get-go these two wore their real-world experience on their real-world faces. Take a long look, if you haven’t in a while, at the cover of each man’s debut — Prine on a hay bale, Withers with his lunch pail — then try to imagine a singer from the last two or three decades in a similar setup. The best he or she could expect would be kudos for a parody well done.

This pre-fame living fueled the empathy in Prine’s and Withers’ songs. They knew what it was to struggle; they knew what it was to be overlooked. And that established a moral framework that held steady even as each man’s circumstances grew increasingly comfortable.

Pop songwriting since the Beatles has implied that a singer is telling his or her own story. But as frequently as not these two were using their voices to tell somebody else’s: “I am an old woman,” Prine sang at age 25 to open one of his signature tunes, “Angel from Montgomery.” Indeed, few have written about old people with more sensitivity than he and Withers in songs like the former’s “Hello in There” and the latter’s “Grandma’s Hands,” both of which illuminate the burdens of figures too often invisible to society.

There’s much more to Bill Withers’ catalog than his immortal hits “Ain’t No Sunshine” and “Lean on Me.” Here, a deeper dive into his short but brilliant career.

As their well-drawn Vietnam material made clear, Prine and Withers believed that protest was most effective in the form of a detailed personal narrative. In “Harlem,” Withers depicts the everyday lives of folks in that neighborhood, including those suffering the neglect of a landlord who won’t turn on the heat; Prine’s “Paradise” laments heavy industry’s destruction of the environment through memories of childhood trips to his parents’ hometown.

And both men knew the value of a great groove. Though we’ve come to think of Prine as a folk or country artist and Withers an icon of R&B, listening to their early stuff reveals how closely aligned they were in terms of rhythm and texture — in their love of acoustic guitar and churchy organ and drums miked so you can hear stick against skin.

Consider that “John Prine” was produced by Arif Marden (who also worked with Aretha Franklin and Donny Hathaway) and Withers’ “Just As I Am” featured playing by Stephen Stills and Jim Keltner, and it makes even less sense to think of the two as representing different traditions.

Call this what it is: pure music of the mixed-up American soul. If yours is ailing, it’ll help.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.