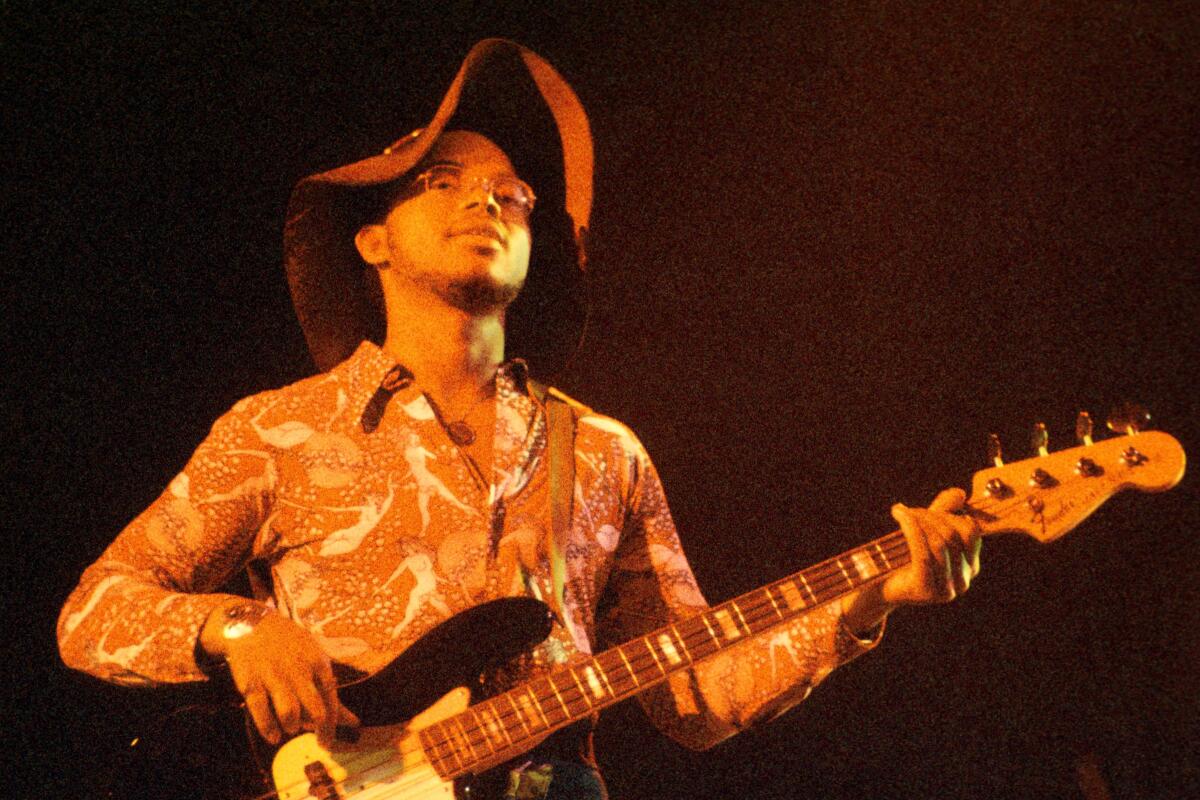

B.B. Dickerson, bassist and co-founder of Southern California band War, dies at 71

- Share via

Few bass lines can be said to define an entire West Coast vibe, but War co-founder B.B. Dickerson’s funky maneuvers on “Low Rider” — along with a well-placed cowbell — did just that.

Dickerson, who died Saturday at 71, made his name driving the bottom end of a seven-man Southern California musical institution known for hits including “Cisco Kid,” “Why Can’t We Be Friends,” “Slippin’ Into Darkness” and “Spill the Wine.”

Howard Scott, War co-founder and Dickerson’s uncle, said that Dickerson died in a Long Beach retirement home due to complications from a series of strokes.

Sampled by hundreds of artists including Janet Jackson, Kanye West, De La Soul, Mac Miller, Madlib, the Beastie Boys and DJ Quik, the rhythms that Dickerson built with drummer Harold Brown and percussionist Thomas “Papa Dee” Allen united the sounds of rock, soul and Latin music to create an essence that was distinctively Californian.

“Some people call it ass music, others call it street boogie,” Dickerson told Rolling Stone in 1974 — before landing on a single word that separated their music from others: “Rhythm. Our rhythm is different.”

Born in Torrance and raised in Harbor City, Morris “B.B.” Dickerson started playing piano before he was 5, performing and singing at church. When he was 12, he and Scott, who was four years his senior, learned how to play bass and guitar. The Vietnam War put the band’s plan on hold after Scott was drafted. Dickerson, 18, moved to Hawaii.

Upon returning from service and changing their name to the Night Shift, the members of War got a gig backing NFL football player Deacon Jones’ between-season foray into soul music. One of those 1969 sets was witnessed by the Animals’ singer Eric Burdon, producer Jerry Goldstein and his business partner Steve Gold, who as founders of Far Out Productions approached the band with the idea of collaborating with Burdon.

But they needed a new bass player, Scott recalled on the phone from his home in Arlington, Texas, so they beckoned Dickerson. Rather than the Night Shift, Far Out pitched them on changing their name to War and the next year the band, which by then also included harmonica player Lee Oskar, joined with Burdon to release “Eric Burdon Declares War.”

The hit that followed, “Spill the Wine,” set War on a musical trajectory that helped define the sound of Southern California low rider culture in the 1970s. A pure echo of its surroundings, War captured a relaxed essence that coincided with interest in cruising, skating and Southern California car culture. Built for partying and dancing, its songs teamed joy with messages of unity. “Why Can’t We Be Friends,” with its chant-along chorus and proto-rap vocals, was driven by Dickerson’s reggae-informed bass melody. The song reached No. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100 in summer 1975.

A British record producer, Malcolm Cecil became a towering synth innovator and Stevie Wonder collaborator.

Scott called Dickerson “one of the most unique players around because he could play syncopated time with syncopated bass licks and syncopated guitar licks — all that stuff we put together — and still sing while playing all these ninth-notes. He could rock that bass and sing on time.” He accomplished it with a laid-back easiness that came to typify the band’s style.

Roots drummer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson wrote on Instagram that War “was the first out the gate of those bands you just couldn’t identify — were they pop rock (Burdon era)? Were they LatinX? Soul? Funk? Disco? Which one sings? All of them sing? All at the same time?!!”

Dickerson once contrasted War’s music with more up-tempo hits by saying that “some music is full of energy, like taking speed... War music is like taking a spoon of honey or smoking some really bad-ass weed.” Dickerson enjoyed his success, spending it on cars and indulging in the spoils of pop music success. At one point he owned a Bengal tiger.

After he left the band in 1979, Dickerson stepped away from the musician’s life, moved to San Bernardino and opened a head shop. He spent his last years in Long Beach.

His departure came as the founding members of War began a decades-long legal battle over rights to their name. Because of the way War entered into existence, Far Out Productions has long claimed legal ownership of the moniker, and courts have confirmed it. As a result, all but one member of the original War is barred from touring as — or even mentioning a former affiliation with — War when advertising or promoting concerts. Dickerson, Scott and others have long been forced to tour under a different name, which they dubbed the Lowrider Band.

Dickerson was well aware of pop music’s shelf life, he told The Times in 1975 as War was coming off of a two-year recording hiatus. “This is a killer business because people will forget about you in a minute.”

That reality was tough on Dickerson, said his cousin (and Scott’s son) Howard “Scotty” Scott. “He wasn’t really into the money side of things. He didn’t really care about that. But one of the things that he did have a real problem with is not being able to perform as War. He was like, ‘OK, they own the publishing, but I can’t even go onstage and say, ‘Hey, I am who I am.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.