Aimee Mann: ‘I have an enormous amount of compassion for people who are struggling’

Aimee Mann has never felt like more of a musical outsider.

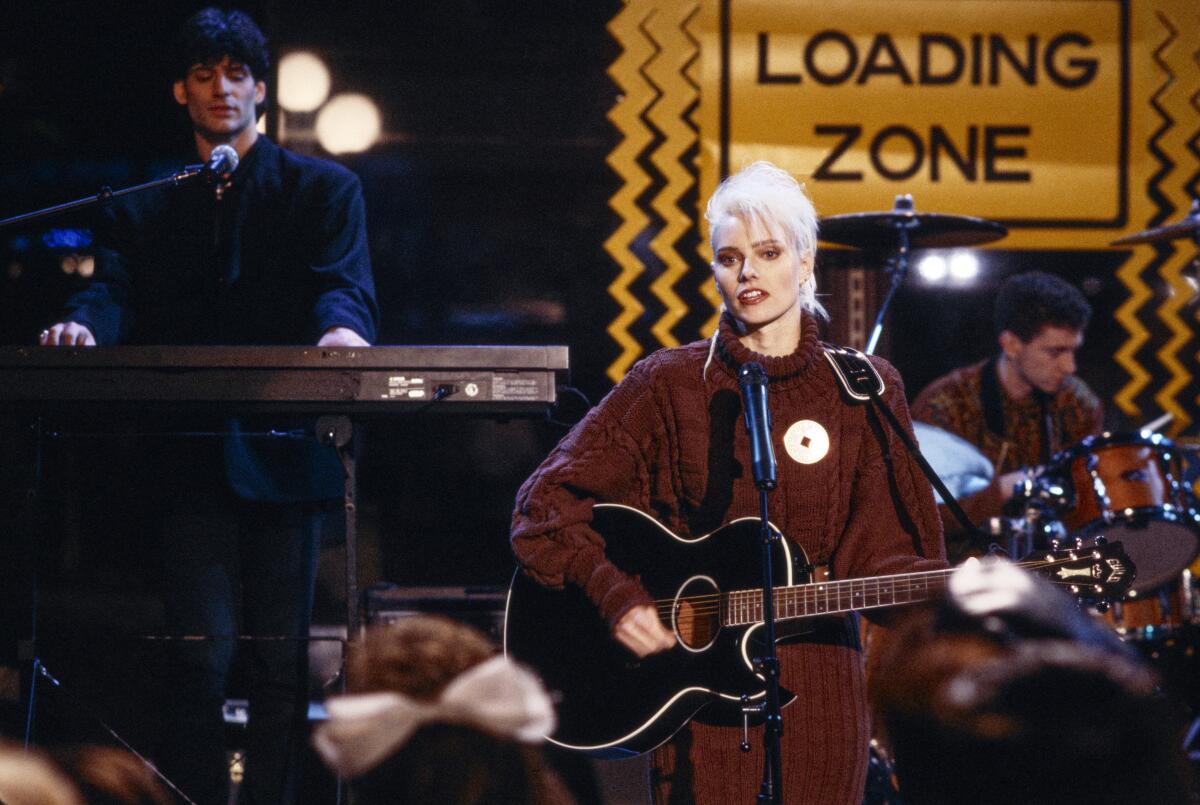

Though the songwriting luminary first emerged into the cultural consciousness in the mid-’80s as the spiky-haired singer and guitarist in new wave sensations ‘Til Tuesday, it is now — as a 61-year-old Angeleno peering through her thick glasses into our Zoom call, donning a pale blue turtleneck and her hair neatly pinned back — that she feels most profoundly out of step.

Mann tells me this one Tuesday morning during an interview about her new album, “Queens of the Summer Hotel,” a collection of elegant baroque pop songs that she completed prepandemic for a planned stage adaptation of the 1993 memoir, “Girl, Interrupted.” The best-selling book chronicles author Susanna Kaysen’s stay at the McLean psychiatric hospital in Massachusetts in the late 1960s, and spawned the 1999 movie of the same name, starring Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie. One of Mann’s songs, a waltz, is about former McLean patients, the poets Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath, and the album’s title comes from the 1959 poem “You, Doctor Martin” by Anne Sexton — “And I am queen of this summer hotel / or the laughing bee on a stalk of death” — who also spent time at the hospital.

“I relate to some of her chaotic thinking, how that fueled her writing but also made it so hard for her to ever find a place to land,” Mann says of Sexton. “There’s a gallows humor to her discussing her time in McLean that I appreciate.”

The play is currently in limbo due to the pandemic. But Mann — whose battles with major labels in the ‘90s over the releases of her first solo albums, 1993’s “Whatever” and 1995’s “I’m With Stupid,” were well-documented — has forged a career by finding her own way when one door closed and she opened another.

Concept albums filled with classical music and explorations of depression and suicide may be rarities in mainstream music today. Mann is known, however, for crafting understated tunes that not only soundtrack devastating stories but propel them. In 1999, she wrote songs for Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Magnolia” that, far from a typical soundtrack, also functioned like musical theater, woven into the plot. It was then too that Mann formed her own label, SuperEgo, through which she continues to release collections of her subtle, Beatles-y story songs, marked by her coolly minimal yet boldly center-stage singing. (As she told Nylon, “It’s a lot more fun to have a lemonade stand than to work for McDonald’s.”) She won the folk album Grammy for her last solo LP, 2017’s “Mental Illness.”

“I don’t know anybody who doesn’t feel the integrity coming off of Aimee Mann,” says her recent collaborator and punk fixture Ted Leo. “You don’t have to know about her history with major labels — and how she released music on her own long before a lot of the rest of the pop world was doing that — to feel the integrity in her songwriting.”

Like Mann’s lyrics, the language of “Girl, Interrupted” is often sardonic and plainspoken, both conversational and literary. And like the book, the narratives of “Queens of the Summer Hotel” depict how life in the late ’60s could be perilously oppressive for women. Collaborating with her longtime producer Paul Bryan, Mann wrote these revelatory songs in a fevered rush. The harmonically rich “You Fall,” “At the Frick Museum” and “Suicide Is Murder” evoke and extend specific moments in the text.

“The book is episodic, with event and character sketches — the story doesn’t make itself obvious — so I thought about what a certain character might sing, or which episodes might culminate in a song,” says Mann, who was brought onto the project by “Once” producers Barbara Broccoli and Frederick Zollo and their daughter, Angelica. “I found it very liberating,” Mann says of writing for theater. “I felt like I could do anything.”

A new Amazon documentary, ‘A Man Named Scott,’ artfully chronicles the mental-health journey of one of hip-hop’s most unlikely superstars, Kid Cudi.

On the highlight “Give Me Fifteen,” Mann describes a sexist doctor who concludes a diagnosis after only brief observation — because “women are so simple after all,” Mann sings wryly, a clear political dimension ringing out. This is how Kaysen is sent to McLean in “Girl, Interrupted.” But “Give Me Fifteen” is also an allegory for a world in which women’s health concerns too often remain dismissed or misunderstood by the medical establishment. “It’s enraging, and every woman has absolutely experienced it — not being taken seriously,” Mann says.

She recently experienced this herself while navigating struggles with vestibular migraine and a nervous system disorder that resulted in worsening tinnitus and distortion in her hearing. “I couldn’t listen to music,” she says. “There was a point where I was like: ‘I guess I’m never working again.’” Mann has improved many of her symptoms by using a daily expressive-writing technique to relieve stress.

“One of the things I came across, in dealing with these symptoms, was that people who historically have had to repress their feelings are more likely to experience neuroplastic symptoms,” she says. “The section of the population that has to more often suppress their feelings are people who are marginalized. Unfortunately, women are still in the marginalized category.”

Mann’s best songs have been, in their ways, about life under patriarchy. ‘Til Tuesday’s 1985 smash “Voices Carry” invoked emotional repression in the context of a toxic relationship — “When I tell him that I’m falling in love / Why does he say / Hush hush / Keep it down now / Voices carry” — with a man who only “wants me / If he can keep me in line.” Fourteen years later, in her late 30s, Mann’s “Save Me,” which closes “Magnolia,” became her masterpiece: a spare, tidily strummed ballad and maybe the most unassumingly beautiful song ever written about connection among damaged people. It was nominated for the Oscar for original song and solidified Mann’s stature as an esteemed songwriter.

That period of her career was not without its difficulties, ones that, she notes, also imbued her with experience that she brought to the “Girl, Interrupted” material. In 2002, in the wake of her solo breakthrough, she entered an Arizona treatment center. “I had a nervous breakdown,” she says. “I was not functioning.” Her diagnosis was PTSD from unresolved childhood trauma, which spurred “fairly severe dissociation.” At the treatment center she forged friendships with others in recovery, some from addiction, and, prepandemic, Mann continued to attend Al-Anon meetings. “I have an enormous amount of compassion for people who are struggling,” she says.

Mann was born in 1960 outside Richmond, Va., where her father was an advertising executive. The childhood trauma was due in part, Mann said, to “a lot of interrupted caregiving.” Her parents divorced when she was 3, after which Mann’s mother and her new boyfriend kidnapped Mann. They took her to Europe and traveled around. Mann’s father was searching for her via a private detective for nearly a year when she was found in England and returned home.

“By the time I saw my father again, it was like he was a stranger, and then I didn’t see my mother again until I was 14,” she says. “I think having two parents where you spend so much time away from them, and then they just don’t seem like parents anymore — that lays the groundwork for later problems.”

Gravitating toward music, her idol was David Bowie. She began playing guitar at 12, and moved to Boston after high school to attend Berklee College of Music, though she ultimately dropped out to play in art-punk bands like the Young Snakes. But atonal dissonance was not her calling, and she soon started gigging around Boston with ‘Til Tuesday instead. The last touring lineup of the band included a young Jon Brion. Before making records with the likes of Fiona Apple and Kanye West, Brion’s first production credits were on Mann’s early solo albums.

As Mann turned to her methodically hooky solo work, she found that she preferred structure in music. “Writing for me is an exercise in order, and not chaos,” she says. “To attempt to describe something — to make connections, to put pieces together, to try to sum up complicated ideas in a three-and-a-half minute song — that’s trying to put chaos in order for me.”

Mann’s songs keep resonating. Sky Ferreira performed “Voices Carry” live several times before releasing a recording of her cover in 2018, calling it “deeply personal to me lyrically.” In January, the New York singer-songwriter Cassandra Jenkins released her wise sophomore album, “An Overview on Phenomenal Nature,” bearing the influence of Mann’s raw emotion, sage steadiness and the centrality of her words.

“I was really afraid of the term ‘singer-songwriter’ for most of my life,” says Jenkins, who grew up with the archetypes of protest singers or coffee-house confessionalists. “I turned to Aimee Mann to find that songwriting could be more sophisticated. She offers an expansive definition of what a singer-songwriter can be, with the very self-possessed nature of a bandleader.”

The scope of Mann’s work keeps growing with “Queens of the Summer Hotel,” as with another project she is currently pursuing: a musical based on her 2005 record “The Forgotten Arm,” also a concept album, about a young woman and boxer-addict who fall in love and flee home.

Mann’s personal cultural intake is largely extra-musical these days: At her home in L.A., which she shares with her husband, fellow singer-songwriter Michael Penn, she has recently been rereading the early 20th century novels of Theodore Dreiser. “I have weird tastes,” she says of her literary preferences. “1915 is kind of my favorite period.”

Reflecting on her trajectory, I ask Mann if there is anything she sees more clearly now than she did coming up in the music world decades ago. “That was the era where, god help you if you got labeled ‘the difficult female artist’ — that would be the end of the story,” she says. “But I was stubborn too. I just always wanted to get better.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.