The Offspring reflects on 30 years of ‘Smash’ with plenty of self-esteem

In August 1994, Jason Mclean was gearing up to celebrate his 21st birthday. As a punk rock diehard, he was ready to party in a fashion that suited him best: a backyard brouhaha. What he didn’t expect was for one of his favorite bands to play his bash right as it was starting to ride the wave of megastardom. The rising band was a group from Garden Grove called the Offspring.

As the beer flowed and good times rolled at Mclean’s party, word trickled out that founding band members Bryan “Dexter” Holland and Kevin “Noodles” Wasserman came prepared with a set that befitted their longtime pal whom they nicknamed “Blackball.” Mclean earned the name after heckling the band to perform its song of the same name so often that Holland promised to play it if he’d shut up … which they did but he didn’t. The party was a big hit until the cops showed up with riot gear and helicopters surrounding the street, cutting the festivities short before things had a chance to really get rocking.

“It was so insane,” Mclean says. “There were so many people there and it was a lot of fun. Looking back, it’s still pretty wild they just played at a friend’s backyard birthday party at that point.”

From the top of 1994 to this party, a rapid sea change in punk rock saw four dudes from Orange County become the next big thing. Holland was a student at USC, already with a bachelor’s in biology and a master’s in molecular biology to his name, and was working on his PhD. Noodles worked as a janitor at Earl Warren Elementary School in Garden Grove. A hair less than a decade earlier the pair, along with Holland’s high school cross-country team pal Greg Kriesel, joined forces to form Manic Subsidal, before later changing their name to the Offspring. With the release of their third studio album, “Smash,” they soared to heights they never expected.

The Offspring’s previous album, “Ignition,” was released in late 1992. Signed to esteemed L.A. independent label Epitaph earlier that year, the album sold in the low-to-mid five digits in terms of copies, highly respectable for a new band. After spending 1993 on the road with NOFX and learning about the rigors of the road, Holland spent time writing what he thought would be lyrically and sonically a natural follow-up.

“It was very important to them [Epitaph] that we get an album out every year,” Holland told The Times. “That’s what Bad Religion did: follow up quickly and consistently.”

At the time, the Offspring was very much a DIY operation. So much so that it didn’t have a manager. When “Ignition” was released, Holland reached out to Jim Guerinot, whom they knew as Social Distortion’s manager and who had a spell managing the Vandals. Guerinot at the time, however, was busy with his day job as the general manager of A&M Records and politely declined. As a consolation prize, Guerinot gave Holland Goldenvoice head Paul Tollett’s phone number, which allowed the Offspring to open for Fugazi at the Palladium.

When it came time to record, the quartet originally wanted to stay close to home. The idea of making the 40-plus-mile slog to North Hollywood was unappealing. Ultimately, at the behest of their producer Thom Wilson, who lived in an RV in NoHo at the time, the group decamped at Track Record. On a tight indie-label budget, the band members had to ensure that the sessions didn’t run over and that they were able to maximize their time there. “We got [studio] time on the cheap — like half price,” Noodles says. “If we call that day, and nobody was in there, we’d go.”

“During ‘Ignition,’ the band really came into our own and defined what our sound was going to be,” Holland says. “But ‘Smash’ was a better batch of songs.”

Recording on and off over 20 days in January and February 1994, the Offspring put together the record that would change the trajectory of their career. Holland had ideas for spoken-word sections and wanted a soothing “Bing Crosby-esque” voice to handle the part. With Crosby long deceased, the group went through a handful of voice-overs submitted by an agency before settling on John Mayer (not that one), whose voice opens up “Smash” with “Time to Relax.” “It [the voice-over] was over the top and certainly unique,” Noodles says.

Songs like “Nitro” and “Genocide” were written quickly and naturally as they fit in the wheelhouse of what the band was doing. Others, like “Gotta Get Away,” Holland wrote as he was trying to expand the Offspring’s sound. On that song in particular, he knew that the album needed a mid-tempo track to balance out the rapid-fire punk that defined “Smash.”

“‘Self Esteem’ was literally one of those moments where I woke up one morning with the melody in my head,” he says. “I had the bass line and the vocal melody for the verse. Then the chorus came a couple of weeks later.”

The last song recorded happened to be one of the album’s signature songs. “Come Out and Play” was originally an afterthought, but it was one Holland had in mind after witnessing gang and street violence on his drive to USC. He also had the idea to incorporate another voice-over. Unlike the smooth pipes of Mayer, he enlisted Blackball to utter the now-iconic phrase “You gotta keep ‘em separated.” Blackball needed just five takes to nail the part and just like that, the album was wrapped.

However, as Blackball and Holland noshed on In-N-Out after the session, the singer warned his pal, who was working at a box manufacturer at the time, that there were no guarantees that his line (and brush with stardom) would make the final cut.

“A month later, so we’re at Iguana’s in Tijuana,” Mclean remembers. “We’re hanging out and Dexter gave me a copy of ‘Smash’ and goes, ‘Yeah, I don’t think they’re gonna put it on the CD.’ I was like, ‘Oh, that’s cool.’ Then he goes, ‘I’m just kidding, they f—ing love it! And they want it on the radio.’”

As soon as the album was wrapped, it was decided that “Come Out and Play” would be the album’s first single. Soon, the single landed in KROQ DJ Jed the Fish’s hands and quickly was anointed his Catch of the Day. “As goes KROQ, so goes the country,” Noodles quips.

And he was right.

Once KROQ added “Come Out and Play” to its rotation, Phoenix and Las Vegas soon followed. Then the East Coast stations picked it up, and when the song landed on MTV the Offspring was bringing the sound of O.C. punk to the nation.

“If I had a nickel for every time I played the Offspring in my career, I would be on a little island right now having a margarita,” SiriusXM DJ Kat Corbett jokes. Working at an indie rock station in Boston at the time, Corbett saw how quickly “Smash” resonated with listeners. “It was so unusual for a punk record to have four singles and a pretty big feat.”

Meanwhile, across town, a familiar face reappeared. As the band’s profile rose, Guerinot’s assistant received a copy of “Smash” and played it for his boss. Intrigued after he remembered Holland calling him a few years earlier, Guerinot called KROQ program director Kevin Weatherly, who confirmed the popularity of “Come Out and Play.” No stranger to hits, Guerinot liked the song but strongly believed in a different track.

“‘Self Esteem’ was the hit,” Guerinot says.

A lot of things have to go right for an indie album like this to strike gold, never mind go platinum. In 1994, musical tastes were a moving target. Alternative rock ruled rock radio and when Green Day released “Dookie” that February, it kicked open the door for the latest wave of punk to dominate. Rock music and hip-hop ruled the top 40 charts and thus, radio stations. Combine that with KROQ’s rock influence along with memorable music videos and catchy hooks, the timing aligned for “Smash” to dominate.

“‘Smash’ resonated in such a huge way for a number of reasons,” Yasi Salek, the host of “Bandsplain” and “24 Question Party People” podcast, says. “It came out the day Kurt Cobain was found dead, which beyond symbolic, also very quickly left a void, and there were still a lot of angry young people in search of angry young anthems.”

In addition to “Smash,” 1994 saw seminal punk albums released by Rancid, NOFX, Jawbreaker and Bad Religion. Things aligned, but “Smash” catapulted the Offspring beyond Southern California.

As it turns out, Guerinot was wrong and right. “Come Out and Play” and “Self Esteem” were massive hits. The latter, with its intro of “La-las,” was unlike anything on the radio at the time and with Holland’s deprecating lyrics about not having self-esteem, it was a song that struck a chord.

Despite the rapid success, the Offspring didn’t make the immediate jump to arenas, nor were the members quick to leave their daily lives behind. It took convincing for Noodles to take a leave of absence from his day job (and pause his health insurance and pension) to pursue his punk rock dreams, and the same for Dexter, who had to put his PhD on hold.

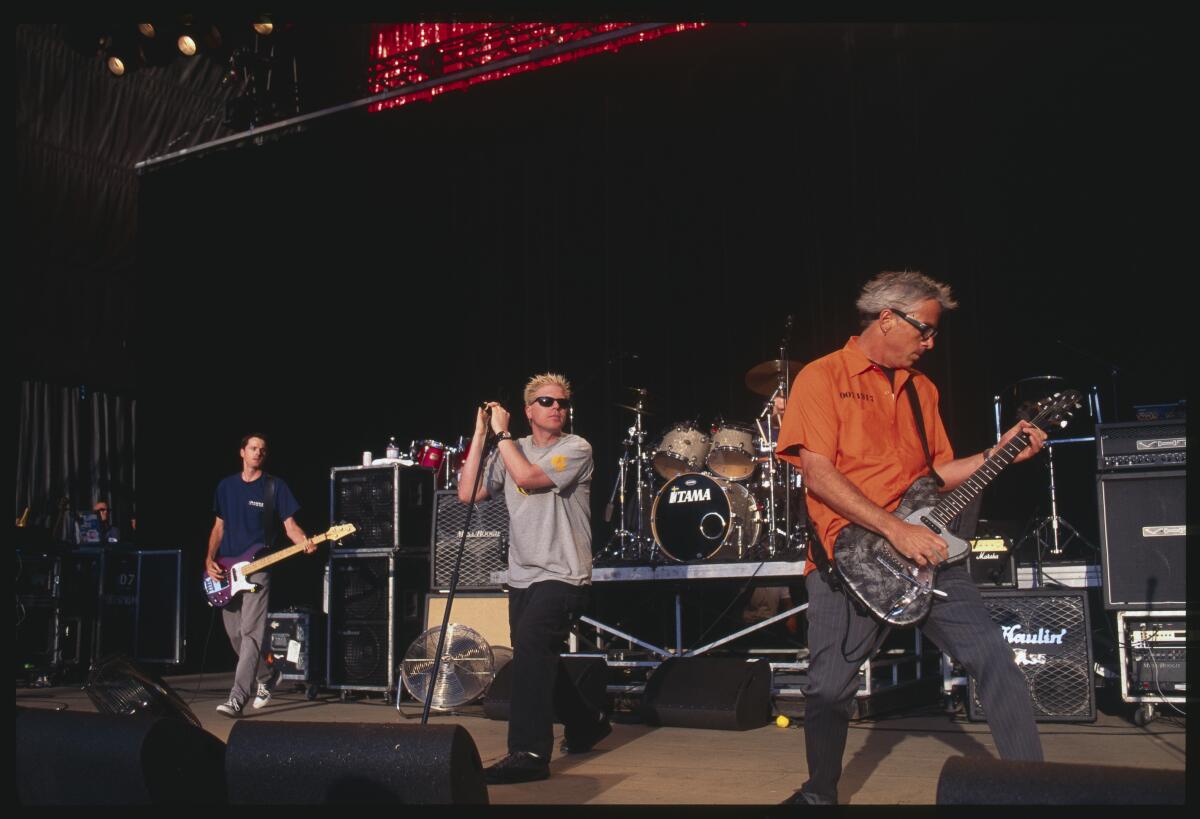

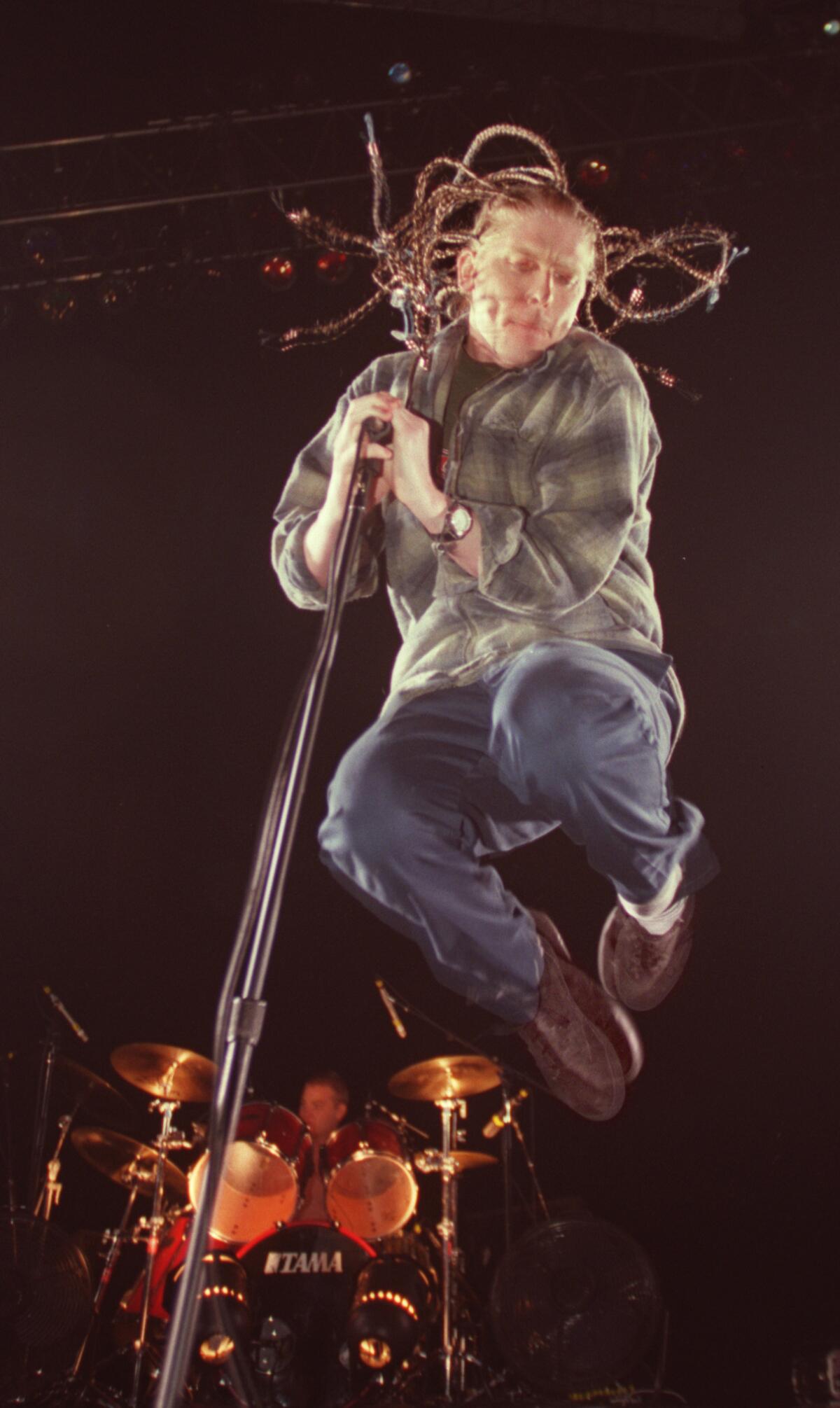

Once the Offspring hit the road, it started small, playing locally at clubs like Whisky a Go Go before moving up to places like the Palladium after “Self Esteem” was released. The band members were wary of moving too fast and being overexposed. With their punk roots and history of playing at venerated DIY punk venue 924 Gilman Street in Berkeley, the band refused opportunities that their peers would have killed for, in particular turning down a coveted performance slot on “Saturday Night Live” at the album’s peak.

“For years, [“SNL”] booker Marci Klein wouldn’t talk to me,” Guerinot says of the fallout.

Bad Religion was the band’s north star. Hearing that the L.A. punk veterans sold 200,000 copies of an album was unfathomable and the ceiling of what they could achieve. “Smash” went platinum six times in 1994 alone and became the bestselling independent album of all time; to date, it has sold 11 million copies worldwide.

Naturally, as the album continued to sell, the major labels came calling.

“I think the moment I realized this was blowing up was when I lived in a small apartment and some major-label A&R guy came to my door to hound me,” Holland recalls. “I said, ‘Well, I’m kind of busy right now I’m taking out the trash.’ And he said, ‘Well, can I walk with you to take out the trash?’”

Nevertheless, in the spirit of its Orange County forefathers, the Offspring’s brand of punk reflected the angst of the suburbs and brought it to the world. It also put the region on the map for contradicting the idea of O.C. as a sterile cultural wasteland. “Smash” catapulted the Offspring to fame and instead of collecting pensions and becoming renowned academics, they became punk rock stars and have been for 30 years.

“We never thought this would be a viable career, but we might be able to do it for a couple of years while we’re going back to school,” Noodles says incredulously. “When we were touring on the [band’s fourth album] ‘Ixnay [On the Hombre]’ cycle, I realized, ‘It’s been three years; if I go back to being a janitor, now I’ll have to start at the bottom rung.’”

“We were in our 20s,” Holland says. “The fact that we were able to put something together that people still like, I’m really proud of that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.