Alex Van Halen doesn’t ‘sugar coat’ complex relationship he had with Eddie in new book ‘Brothers’

If rock music history has taught musicians anything, it is this: Don’t start a band with your sibling. Just ask Oasis co-founders Liam and Noel Gallagher, whose well-documented mutual enmity makes their upcoming reunion tour as much a source of morbid curiosity as of excitement.

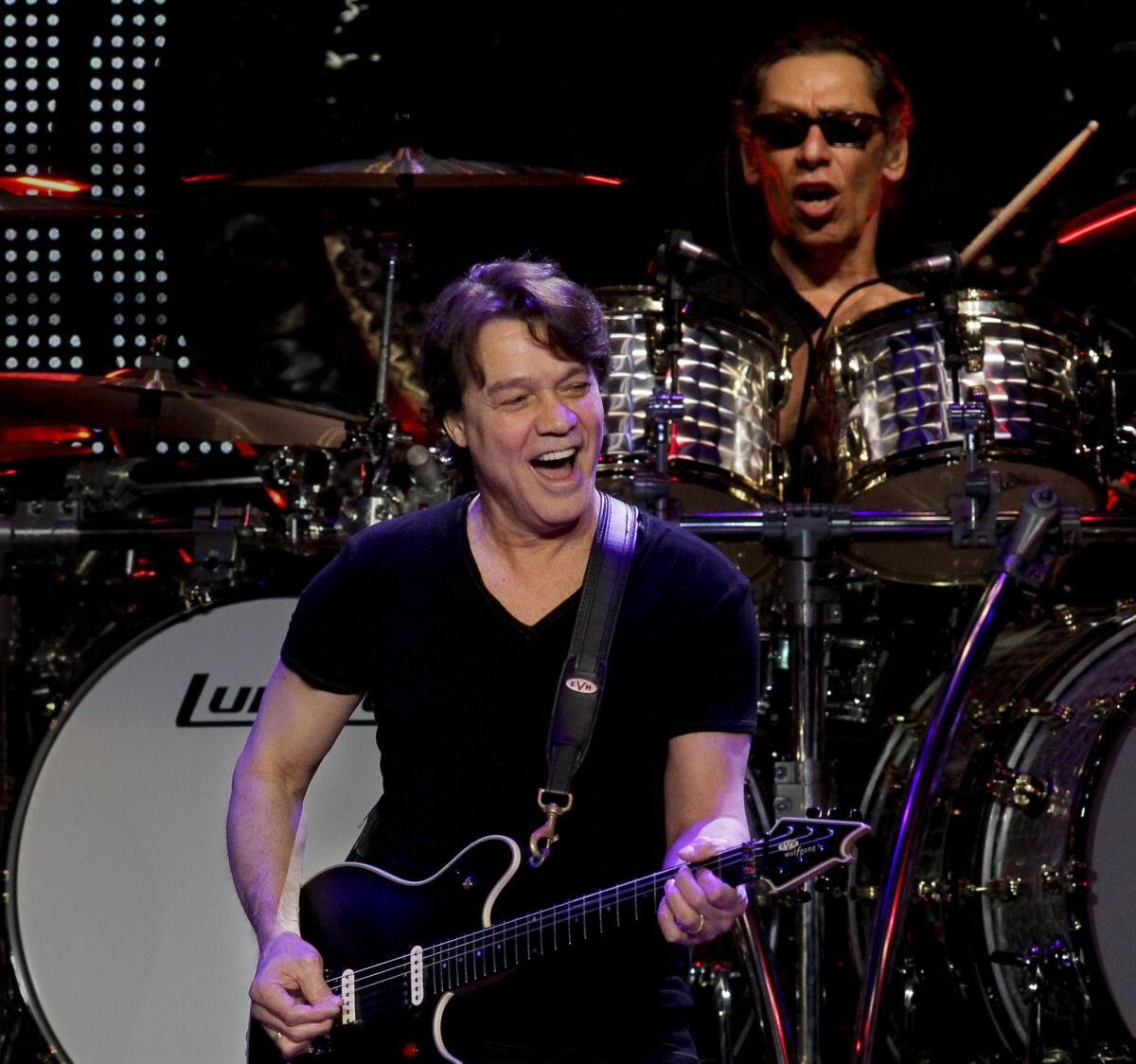

However, Van Halen was something different. The powerhouse hard rock band co-founded by Alex and his brother, Eddie, sold over 70 million albums during their nearly four-decade run. It was Alex and Eddie who started the band as teenagers in their Pasadena basement, who recruited locals David Lee Roth and Michael Anthony to join the lineup, and who guided Van Halen into the highest rung of rock stardom . When Eddie, a pathbreaking prodigy who changed the way the electric guitar was played, died of cancer at 65 in 2020, it was not only the end of the band, but also a tight bond that had lifted Van Halen up from playing suburban house parties to football stadiums.

With his book “Brothers,” Alex has written an elegy to Eddie, and their complex dynamic that was tested by drug abuse, power trips and all the other common traps that befall megastars who once shared the same bedroom. “This is a happy-sad moment for me,” says Alex about his book, which was written with writer Ariel Levy. “I’ve tried to take an objective view of things, and bring it all to light. But I didn’t want to be self-serving. I tried not to sugar coat the story.”

“Brothers” contains its share of “hey, look at us!” set pieces, but it’s surprisingly frank in regard to the fraught dynamics of Van Halen, particularly the push-and-pull between the two brothers and lead singer David Lee Roth. But it begins, as all rock stories do, with young men brimming with ambition and self-confidence, eager to prove themselves and willing to work hard to get there. What’s conspicuously absent is the rejection of the elders, the piss-off to the parents.

Their father, Jan Van Halen, was a professional jazz saxophonist, a man who prided himself on his professionalism, his ability to get people up and dancing by any means necessary. When the Germans invaded Holland in 1940, Jan decamped to Indonesia, where he met Alex and Eddie’s mother, Eugenia. It was Eugenia who pushed piano lessons on her sons, even though they preferred the hot swing of their father’s music. When the family moved to California in 1962, Jan took a job as a janitor, and moonlighted as a freelance jazz musician with some fellow Dutch players.

“My father taught us everything we needed to know about being pros,” Alex says. He is the presiding spirit of the book, the voice inside their heads when things get dicey with the band, or when they find themselves pondering next moves. “He showed us by example,” Van Halen says. “He was so dedicated. He had all of these maxims, like ‘obstacles in the way become the way forward.’ He was intent on playing, no matter what was thrown at him. He was disciplined and nothing was going to stop him. We picked that up as an article of faith.”

Once the family settled in Pasadena, Alex and Eddie soon discovered the wonders of guitar-driven rock and roll — Cream, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath — and a new vista opened up to them. Alex was initially drawn to the electric guitar, and Eddie to the drums. That all changed when Eddie tried out Alex’s guitar during one of their epic garage jam sessions. “I was like, yea, I think you should go for guitar, dude,” says Alex. “We both knew he had a talent for it right off the bat.”

In a few short years, Eddie Van Halen would become one of the most influential musical innovators of the 20th century, a fleet-fingered, melodically sophisticated virtuoso who changed the way guitarists approached their instrument. “Ed was born with a gift, but he knew he had to cultivate that gift,” says Alex. “There was never a waking moment when Ed wasn’t with his guitar. He worked day and night, disassembling and then refashioning his guitars to suit his sound, practicing endlessly. It was all he cared about.”

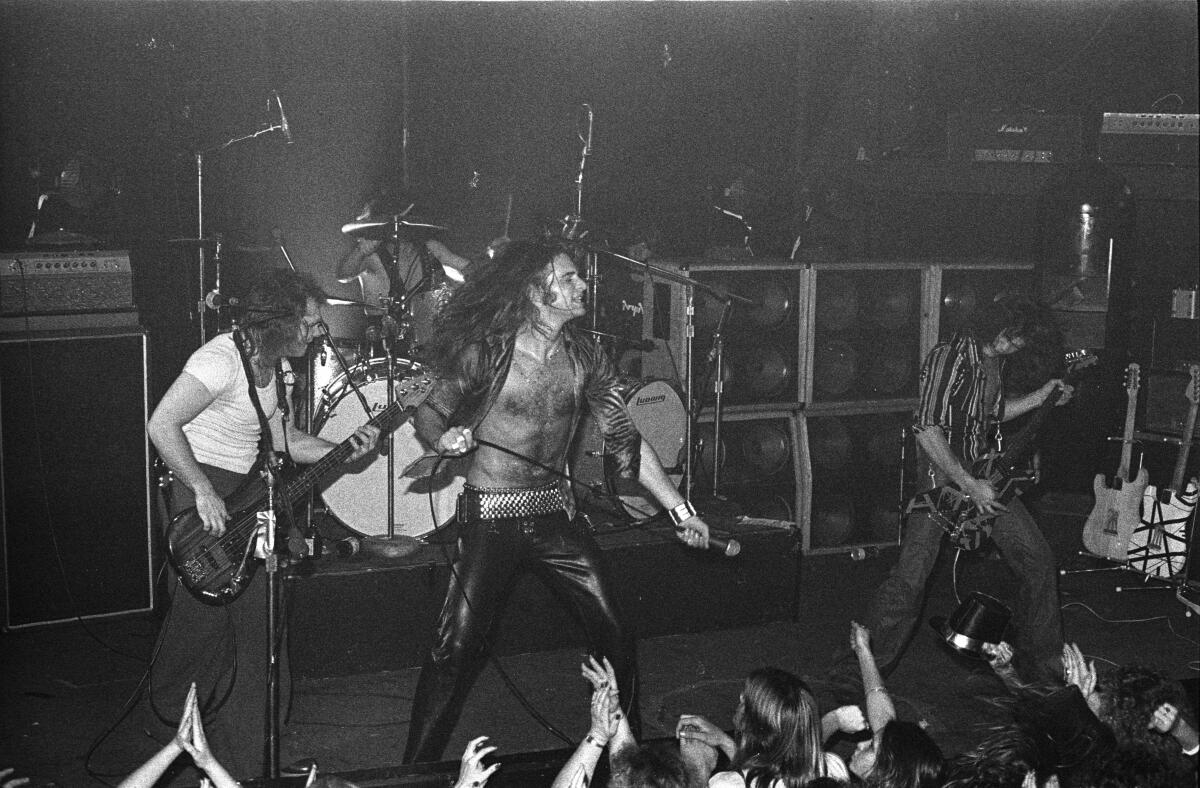

Van Halen’s singer David Lee Roth was an outlier, a flamboyant scenery-chewer whose tastes ranged from show tunes to the Latin lounge music of Louis Prima. Still, as is the case with great bands, the disparate elements coalesced into something unique. “David sang ‘Ice Cream Man’ at his audition, which we thought was his song, but it was this old blues tune,” says Alex of the song that wound up on their mammoth self-titled 1977 debut. “We thought, this guy’s got something unique, even if it wasn’t what we were into.” Jan Van Halen also appreciated Roth; he knew his sons needed some visual locus for their band, something to appeal to an audience beyond teenage air-guitar aficionados, i.e., pimple-creamed boys.

“It was another lesson from our father: You always need visuals, something for the audience to grasp, in order to get the music across,” Alex says. This tension — between Roth’s love of visual flash and the brothers’ purist musical approach — yielded major dividends. Van Halen’s first three albums — ”Van Halen,” “Van Halen II” and “Women and Children First” — all sold in the multimillions. Then MTV, which debuted in 1981, changed the game, quickly becoming the primary driver of record sales. It was around this time that Eddie, who had built his own home studio, started listening to a lot of orchestral music, and began fiddling around with riffs played on his Oberheim OB-xa keyboard. When he played Alex the opening hook to a song he was working on, his bother bristled, but “Ed’s attitude was, ‘let’s take a risk, let’s get outside of what we know,’ ” he says.

Alex and the band capitulated, with the proviso that the video would be free of gimmickry. The resulting song “Jump,” from the band’s album “1984,” became a global earworm, the song that Alex claims “will be the one that we will be remembered by.” The video, an austere affair with the band lip-syncing in front of a white background, became ubiquitous; “1984” became the first Van Halen record to reach No. 1 on Billboard’s album chart.

Then, with little warning, Roth jumped. “He couldn’t handle the fact that Eddie was getting more attention than he was,” Alex says. “He kept asking Eddie to play fewer guitar solos. Dave was convinced he was going to be a movie star.” And just like that, the incarnation of the band that Alex calls “the real Van Halen” dissolved at the peak of its popularity. “1984” wound up selling north of 10 million copies.

Van Halen didn’t miss a beat, recruiting Sammy Hagar as its lead singer and producing a series of multiplatinum records. But Hagar’s macho vocals and generic pop-rock songs couldn’t summon the Sherman-tank stomp of the Roth incarnation. When the band wasn’t touring, Eddie hunkered down in his home studio for weeks at time, drinking heavily and smoking cigarettes incessantly — overwhelmed, Alex writes, by the burden of being called the greatest guitarist on the planet.

Van Halen was diagnosed with neuropathy in his legs a few years ago and no longer plays drums. But his old band is still very much top of mind; he is currently sifting through the band’s vaults, trying to find unused material to release that won’t come off like some cheap cash-in for the fans. “I F—ing miss Ed like crazy,” he says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.