Commentary: Three years later, rapper Drakeo’s killing leaves behind more questions than answers

- Share via

After three years, the grave remains unmarked. But on a dreary Sunday afternoon last fall, bouquets of white roses and blue hydrangeas enlivened the Spanish marble columbarium where Drakeo the Ruler is interred. About two dozen friends and family members gathered at Forest Lawn in the Hollywood Hills to commemorate what should have been his 31st birthday. The mood was like an eternal shiva — the celebration of the South L.A. rapper’s cinematic life is muted, the search for meaning and healing unending.

The circumstances of Drakeo’s demise — a Caesarian assassination plot executed backstage before his scheduled performance at the Once Upon a Time in Los Angeles music festival in Exposition Park — explains the lack of a proper headstone. Family and friends feared that the killers or their allies, who remain at large, would desecrate any memorial, as they did to tributes that cropped up shortly after his death. (A wrongful death civil trial against the promoters, security companies and venue owners is scheduled for November.)

Last week marked the third anniversary of Drakeo’s funeral, but the unsolved case has produced more questions than answers. How is it possible that no arrests have been made in one of the most high-profile killings of recent memory — one where ample video footage exists, and which occurred in an ostensibly secure area in plain sight of hundreds of VIPs, security and multiple branches of law enforcement? Why did the detectives from the California Highway Patrol, the agency tasked to investigate, fail to contact numerous witnesses connected to the case, including me — a journalist who has publicly written about observing the attack? And why does it feel like large swaths of the local hip-hop world not only want to pretend that the killing never happened, but simultaneously obliterate all evidence of Drakeo’s era-defining impact?

During Drakeo’s memorial at what’s been dubbed the “Disneyland of Death,” the calcite-white sun cast long shadows across the grass. Drakeo’s soon-to-be 8-year-old son, Caiden, and his 6-year-old nephew, Devante Jr., laughed, wrestled and chased each other over the cemetery’s rusting bronze plaques. From the way that his line of vision narrows when he smiles, to how he crosses his arms and rolls his eyes, Caiden uncannily resembles his dad.

Drakeo’s younger brother, Devante, a rap star better known as Ralfy the Plug, played tracks off his phone from the posthumous Drakeo album that he curated. “The Undisputed Truth” eventually peaked at No. 4 for hip-hop album sales on iTunes — a significant achievement for a record released without a major label or distributor. Pitchfork later hailed it as “the culmination of what should have been a generational talent’s early-middle period.”

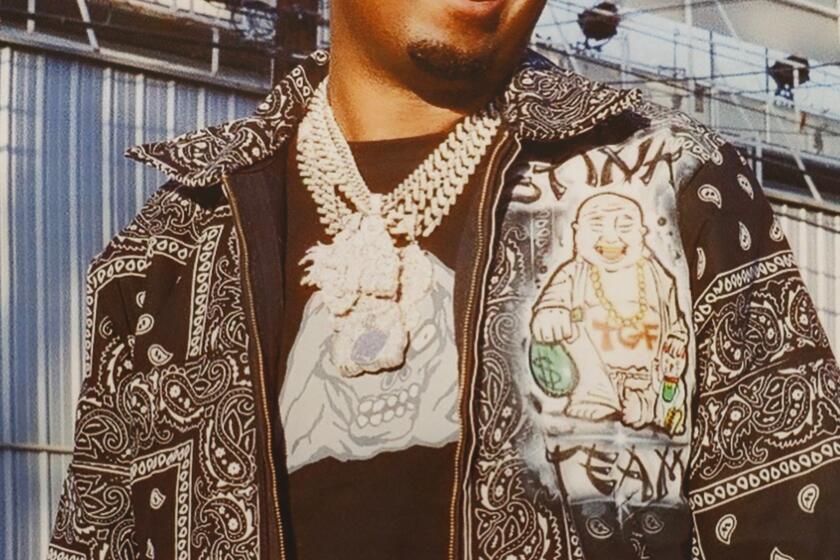

Drakeo called his brand of hip-hop “nervous music,” which he described as the music that you make when you’re driving around South L.A. in a $100,000 car, looking over your shoulder at every red light to see whether you’re being followed by a cop or a killer. His patented lingo, cadences, body language and personal style revolutionized and rebuilt the foundation of modern California rap.

“Drakeo’s flow influenced the whole world,” said Watts’ 03 Greedo, who arrived at the memorial in a late-model purple Aston Martin and a custom-made “Long Live Drakeo” hat. His emergence in the late 2010s alongside Drakeo made them the region’s reigning high fashion rap outlaws.

“My evil twin made s— look cool,” Greedo said. “Usually when people come up with new lingo it’s corny, but never Drakeo. Almost no one understood it at the time, but now everyone copies it. I miss being in the studio with someone that good.”

I first met Drakeo in the Los Angeles County Jail at the beginning of 2017. Through 6-inch plate glass, I interviewed the rising star shortly after sheriff’s deputies raided his old apartment near LAX. The deputies had arrested him after discovering firearms stashed in a loveseat — none of which were used in a slaying that investigators would attempt, for years, to pin on him. After the prison guards escorted Drakeo away that afternoon, I wouldn’t hear from him for nine months.

After serving his sentence, I profiled Drakeo for The Times, highlighting his millions of streams, sold-out shows and the rave reviews for what became his masterpiece, “Cold Devil” (later included on Rolling Stone’s “Greatest Hip-Hop Albums of All Time” list despite its DIY release). Almost immediately, things went awry. In March 2018, a sprawling Sheriff’s Department dragnet led Drakeo, Ralfy and their rap crew, the Stinc Team, to face a raft of charges that ranged from first-degree murder to petty credit card fraud. Though Drakeo often mocked gang life (and never joined a set), the state petitioned to classify the Stinc Team as an illegal criminal organization. Drakeo’s lyrics were weaponized as evidence of guilt.

The investigation revolved around a December 2016 homicide at an adult pajama party in Carson. According to homicide detectives, two Crips (one of whom also was a member of the Stinc Team) shot a Blood. No one accused Drakeo of pulling the trigger or even having the desire to harm the deceased. But prosecutors argued in court that Drakeo had plotted to kill someone entirely different — a rap rival said to be going to be the same party — and as the leader of the “gang,” he was responsible for all violence committed by his entourage. As for the putative rap opponent, he wasn’t listed on the flyer for the pajama party, never appeared at the event and later claimed on social media that he didn’t even know about it.

For nearly three years, Drakeo was held in downtown’s Men’s Central Jail. Bail was repeatedly denied. Roughly half his sentence was spent in solitary confinement, which he described to me as “definitely torture. “It f— with your head,” he said, and makes you [more inclined to be] violent.”

We became close during his season in hell, where he was surrounded by what the rapper described as hardened Mexican Mafia killers. During his trial, there were days where he’d call before court, during lunch break and at night. Any pretense of my objectivity was abandoned as soon as the facts were aired in public. Being honest, regardless of natural bias, felt far more important than any flawed presumption of “both sides” neutrality. And from what I witnessed in court, the prosecution’s case was flimsy at best, a grotesque miscarriage of justice at worst.

Representatives for the L.A. district attorney’s office did not respond to my requests for comment on the prosecution strategy of that 2017 murder case.

In the summer of 2019, Drakeo was acquitted of all murder charges. But the jury hung on two counts: shooting from a motor vehicle and a rarely-used gang conspiracy law. One of the convicted shooters was said to have fired from the back of Drakeo’s parked car; under California law, the driver of a vehicle can be accused of the same charge as the shooter. In both instances, the votes tilted in Drakeo’s favor. But prosecutors sought a retrial. Bond was once again refused.

In March 2020, COVID-19 caused the indefinite postponement of the state’s second inquisition. By that fall, Drakeo had become a cause célèbre. The New Yorker claimed that the details of his case were “so nonsensical that the story could be read as satire.” The Atlantic wrote that “the national reckoning over policing means that more Americans could stand to seriously listen to the music of Drakeo.” An album recorded over the phone in a place that the American Civil Liberties Union once called a “modern-day Medieval dungeon” was widely hailed as the best ever made from jail.

The day after the November election of reformist Dist. Atty. George Gascón, the prosecutors finally offered Drakeo a deal: If he pled guilty to the two remaining charges, he could come home that afternoon. Within a few hours of regaining his freedom, Drakeo had already recorded several songs that have now racked up tens of millions of streams. But for all of his newfound fame and fortune, the internecine conflicts of the L.A. streets haunted him.

If you accept the widely believed narrative, members of the Bloods were determined to enact retaliation for the initial 2016 killing. And Drakeo was constitutionally incapable of backing down. In podcast interviews, Instagram posts and diss songs, a long-standing grievance metastasized into a bitter vendetta between Drakeo and what appeared at times to be every gang member in Inglewood (especially after Drakeo responded to their claims about killing one of his best friends by releasing a vicious diss track called “IngleWeird”).

The brazen nature of Drakeo’s slaying and the widespread rumors tying some of the biggest names in L.A. hip-hop to the plot, has created a schism that divides the community to this day. And for those intimately connected to the deceased, there is no respite.

Constant sorrow coexists with countervailing strength and perseverance. During Drakeo’s murder trial, his mother, Darrylene Corniel, and I often sat next to each other. While her children fought for their freedom, her optimism and sense of belief never faltered. In the aftermath of Drakeo’s death, she has single-mindedly kept her family together and forged a tight bond with the dozen or so members of the extended family who loved her child. For this, she credits her faith.

“I wouldn’t have made it without God,” Corniel said. Her voice and countenance transcend conventional religiosity. Corniel recalled a story from the night of Drakeo’s death — while she waited in the ER for the word from the surgeons.

“I started praying right there in that hospital. Speaking in tongues. I didn’t care who was there or who saw it,” Corniel said. “After the prayer finished, the doctor came in and said, ‘I’m sorry, Darrell didn’t make it.’ I couldn’t look at him. I was in shock. I kept saying ‘Darrell Caldwell? Are you sure you got the right one?’ ”

Much later, Corniel’s sister told her that after witnessing the fervency of that prayer, she knew that Corniel was going to eventually make it out on the other side.

“That’s when I told her: that prayer wasn’t for my son,” Corniel said. “That prayer was for me. My son had already passed, but I had to be built up before the doctor told me what happened. If I hadn’t done that first, there’s no telling how it would’ve gone.”

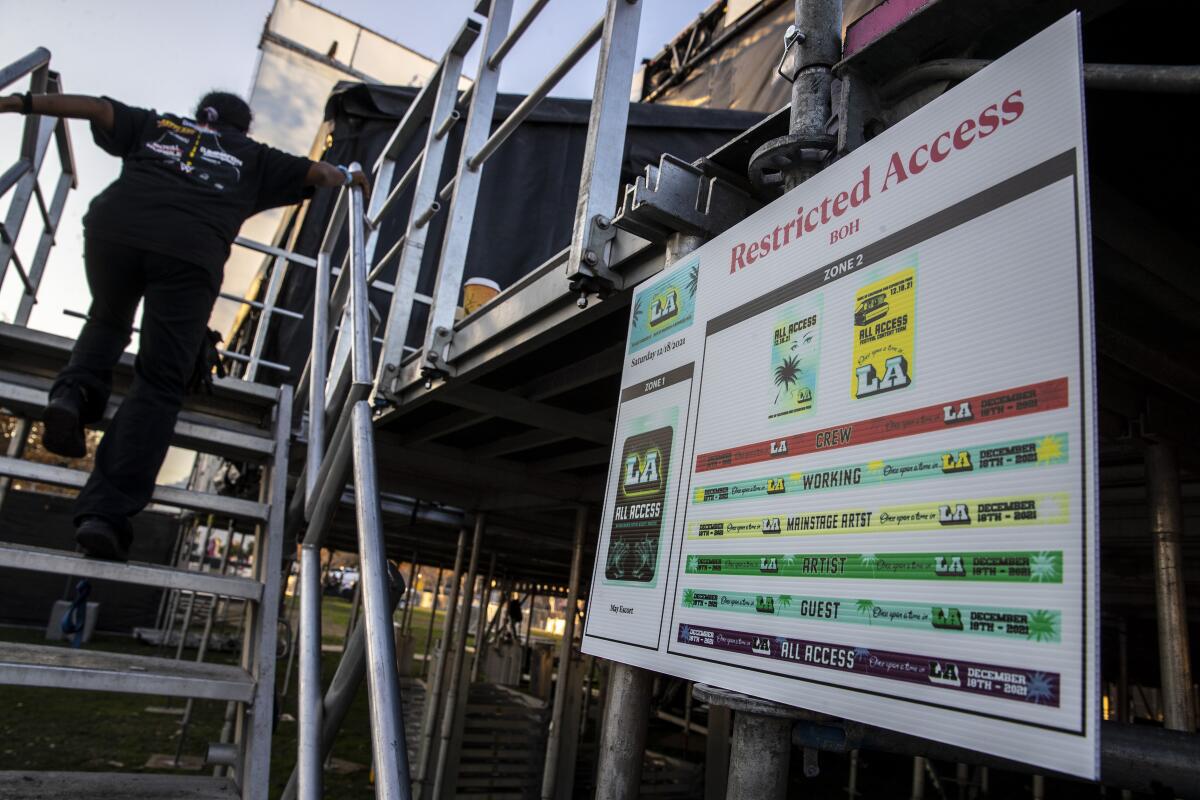

From the start of Once Upon a Time in L.A., something seemed off. An eerie winter solstice wind whipped across the Exposition Park blacktop. Despite the various hired security agencies present, their approach to monitoring potential threats seemed negligent (according to my own observations and others who I spoke to at the festival). The stage layouts were sprawling and disorganized. An air of lawless volatility was pervasive backstage. The festival lineup boasted everyone from 50 Cent and Snoop Dogg to the Isley Brothers and War — and most of the big West Coast street rap stars from the last decade, including several artists from Blood sets that had declared Drakeo a mortal enemy.

There’s little doubt that the assault was carefully planned. After watching Al Green croon, I walked out of an enclosed VIP area at the Banc of California Stadium to meet Drakeo, who had just arrived. The plan was to do a half-hour set, collect his $50,000 paycheck and get out as fast as possible. About a dozen of us set out for the G-Funk stage, where Drakeo was scheduled to perform. Almost immediately, a half-dozen men in ski masks and burgundy hoodies loudly taunted Drakeo and the Stinc Team. A brawl broke out.

At first, the numbers were evenly matched. Drakeo and his crew held their own: exchanging jabs and uppercuts. Their foes retreated and scattered after just minutes of fighting. The threat seemed neutralized. But after a minute or two, masked assailants sprinted out from the shadows of the parking lot and other backstage areas, a tidal wave of attackers dressed in red quickly surrounding Drakeo and his friends. A private detective who later volunteered his services to Corniel estimated that 113 assailants attacked seven members of the Stinc Team. Their primary target was clear.

I didn’t see the knife slit Drakeo’s throat. A rush of fighting and commotion suddenly swelled up behind the stage where Green had just sung “Love and Happiness.” And then the killers scattered into the darkness.

When I try to remember that night, certain sounds and images remain indelible: One of the attackers leaping up onto a pillar, ripping off his balaclava and screeching, “Soo woo!!!” Drakeo’s motionless body, slumped on the asphalt, rivulets of blood seeping from his neck; the wait for the ambulance as he lay dying; the members of the Stinc Team in shock, needing medical attention but treated by the police as if they had provoked the assault.

I remember trying to scramble, weak-legged, toward a festival exit while George Clinton’s Funkadelic played “Maggot Brain” on a faraway stage. As the graveyard requiem kept escalating in its intensity, I remembered the advice that Clinton gave to Eddie Hazel when he first unleashed that voodoo guitar seance: “Play like your mother just died.”

In that moment some inner voice told me that Drakeo was gone. And then the final confirmation at the hospital in the early morning delirium of Dec. 19, 2021. The news was broken to the assembled crowd by Corniel herself, prefaced by a primordial wail — the type that can be unleashed only when body and mind are wracked by a level of pain previously considered alien and inconceivable.

For the first weeks after Drakeo’s killing, I regularly snapped awake at 3:30 a.m., sweaty and disoriented, unsure where I was. My mind felt like an upturned snow globe frosted with falling droplets of blood. Sudden tears were frequent. The wrong song could induce a freefall. Minor frustrations triggered uncontrollable spasms of rage. Therapy offered temporary consolation but no tangible solution.

I wrote a long magazine story about the attack. By then, videos of it were all over social media, but they captured only short bits of a much-longer and larger melee. On YouTube, would-be sleuths dissected the footage and offered their conclusions. Some were wildly off-base; others lined up perfectly with what I’d seen and heard. I kept waiting for the cops to make an arrest. But weeks became months. I assumed that writing a widely circulated eyewitness account of an unsolved murder would’ve led the detectives to attempt to interview me or anyone who I was with that night. But they never did.

About a week before Drakeo’s funeral in February 2021, I had a strange and unforgettable dream — the only one that I’ve experienced that felt remotely prophetic. I found myself riding alongside Drakeo on a mostly empty bus, joking and laughing as if nothing had happened. Then I remembered the killing, and searched for signs of wounds or trauma. But he was happy and intact.

In the dream, I remember understanding that Drakeo was simultaneously dead and beguilingly close. To be sure, I asked, “Are you OK?” And then he smiled bright and exhaled his huge, creaking “Ahhhhhh” laugh and said, “I’m good,” repeating the words twice for extra assurance. Then he vanished from the seat across the aisle. The bus kept soundlessly rolling. From my window, I could see Drakeo now outside, walking slowly alongside the bus on the side of the road. We exchanged a nod of understanding, and it all went blank from there.

There is a natural paradox within the grieving process. A small part of you wants to forget what occurred as a way to shed the anguish, which begins to feel like a permanent lead vest around your chest. Another part of you frantically tries to embalm the memories, fearing the natural deterioration and gnawing terror of time. The knowledge that one day these treasured recollections will melt into a fog of static and dust.

The case of Drakeo is distinct, and not just because his art and iconography have achieved posterity. There is some other incalculable quality: In death, as in life, he’s somehow managed to remain a center of attention and object of controversy. There are circles in L.A. in which it’s considered unwise to even speak his name out loud unless you’re looking for disrespectful rebukes or menacing silence. In others, often among his diehard (and heavily Latino) fan base, he’s revered with almost messianic intensity.

Over the last half-decade, Los Angeles has been plagued by a string of high-profile rap slayings, including Nipsey Hussle, PnB Rock, Pop Smoke and Slim 400. In each circumstance, the motives and conditions were vastly different, but law enforcement nonetheless caught and convicted the shooters (save for a defendant in Pop Smoke’s murder trial who recently took a plea deal in exchange for a 29-year prison sentence). Last October, federal authorities arrested Lil Durk and charged him with conspiracy to commit murder-for-hire against rival rapper Quando Rondo after a gas station gunfight near the Beverly Center left one man dead. These other cases make the lack of justice for Drakeo that much more painful.

“CHP isn’t equipped to handle an investigation of this magnitude,” said Kellen Davis, one of the attorneys representing Ralfy and the members of the Stinc Team in the civil trial against Live Nation, the producer of Once Upon a Time. “LAPD, the Sheriff’s Department and the FBI could have all gotten involved. They always find creative ways to exercise jurisdiction when they want a case. But it’s telling that they opted not to here, especially in a high-profile murder that made so much noise.”

I asked Davis why he thought that the case wound up languishing with the California Highway Patrol, an agency whose homicide department is not nearly as robust as any of the other branches of law enforcement:

“I don’t have evidence to support it, but you can connect the dots,” Davis said. “Drakeo was notoriously outspoken about the ways that the Sheriff’s [Department] investigated him. How the latter kept him on high power lockdown. How they took his 1st Amendment rights away. The Sheriff’s Department has the manpower and the experienced detectives to solve the case, but one could conclude that their history with Drakeo is why they stayed away.”

Representatives for the Sheriff’s Department did not respond to my requests for comment.

During the course of the investigation, security camera footage of Drakeo’s slaying was discovered. The video in question has not and probably never will be seen by the public. Earlier this summer, I was subpoenaed to watch it as part of a deposition in the civil suit. My purpose there was primarily to repeat what I had already reported in my magazine story.

Nothing prepared me for the battalions of lawyers from the eight different defendants named in the suit — including Live Nation, USC and Los Angeles Football Club — asking me to spend hours watching Drakeo’s slaying. Replaying the clip in slow motion, they interrogated me about whether I could identify Drakeo on the screen. They offered a bird’s-eye view, right at the exact moment where someone appears to stab Drakeo. And then I can see myself on the camera — the bludgeoning nightmare all over again — as I watch the body collapse onto the asphalt.

The footage is grainy, shot from what must be a camera positioned overhead. It’s too far away to make out the identity of the attackers, who were mostly masked. But what struck me the most was how many cops and security guards were present watching a massacre.

When I started reporting this story in late November, I asked for a comment from Det. Stephen Kimble, the CHP investigator assigned to the case. He didn’t return multiple text messages and voicemails. An email sent to him on Nov. 21 triggered an automatic away message that informed me that he would be out of the office until Sept. 3.

Eventually, I reached a CHP media coordinator who informed me that Kimble was still on vacation, but he was more than happy to help. When I probed into the status of the Drakeo investigation, he offered a stock answer: The investigation is ongoing; the department is following up on leads.

In December, Ralfy the Plug moved into a six-bedroom, 3,000-square foot Tudor estate in the foothills of northeastern Los Angeles. The boxes were still mostly unpacked, but the large Drakeo plush figurine was already on display in the living room. It’s a tranquil family neighborhood, where people wave while walking their dogs and children play soccer in an emerald park down the street.

This is about as far away as you can get from the unincorporated Westmont section where Drakeo and Ralfy grew up, a place with a homicide rate so high that it acquired the nickname “Death Alley” shortly before the brothers blew up in the middle years of the last decade. Separated by just 18 months in age, Drakeo and Ralfy were so close they seemed like fraternal twins. They did dirt and caught cases together until rap finally offered a legal route to realize their financial ambitions.

The plan was for both to get rich independently. Unlike most of their peers, they’d own 100% of their publishing and masters. Then they’d be free to pursue acting, a fashion line and other entrepreneurial goals. But Drakeo’s death forced Ralfy to fulfill their dreams on his own.

“I’ve done sodas, waters, skateboards, shirts, hoodies. We did shoes twice,” Ralfy said, listing all the Drakeo and Stinc Team branded ventures that have sold out over the last three years.

A recent limited-edition run of Drakeo collectible dolls and designer hoodies had lines of teenagers and 20-somethings curled around Fairfax — the location of the popular Chiefin Heavily clothing boutique operated by the Stinc Team member of the same name.

Overhearing our conversation, Ralfy’s son, Devante Jr., leaps up onto the couch and exclaims: “I miss my uncle, he got killed. He was a rock star like my daddy.”

In the wake of the killing, Ralfy was devastated. But after two weeks, he delivered an elegiac head-held-high doxology to Drakeo (“The Truth Hurts”), and then embarked on a stunningly prolific streak of full-length projects and videos. Had Drakeo’s incandescent wattage perhaps overshadowed him before, Ralfy seized the mantle with inspiring consistency and creativity. He’s since become a regional force in his own right — one single-handedly responsible for burnishing his brother’s legacy.

“I stay busy,” Ralfy said when asked how he’s handled the pain. “I make sure I’m always doing something. Even when I’m doing nothing, I’ll go live on Twitch to stay busy.”

On Dec. 18, the anniversary of Drakeo’s death, Ralfy held a third annual tribute show at the Fonda Theater. The show featured nearly two dozen artists, a veritable who’s who of new L.A.street rappers, including Lefty Gunplay and Dody6, whose names are buzzing after cameos on Kendrick Lamar’s “gnx.”

If Drakeo continues to define the sound of California street rap, his music has also become touchstone for subterranean rappers like Detroit hard-boiled traditionalist Boldy James, outlandish Rochester anti-philosopher RXK Nephew, and North Carolina’s meditative and poetic Mavi. A Tyler, the Creator freestyle over the “Hey Now” instrumental from “gnx” included what had been conspicuously missing from Lamar’s study of Drakeo’s style: an “RIP the Ruler” shoutout. And just last weekend, Justin Bieber posted a song from “The Undisputed Truth” on his Instagram Story.

“It wasn’t just rapping, Drakeo was the whole package,” Ralfy said, describing his brother’s universal appeal. “He changed the way these [people] dress, the way they walk, the words they use, the selection of beats. Drakeo brought a finesse and a charisma to everything. He brought the sauce to L.A.”

At the tribute, fans flocked to buy $100 Drakeo hoodies and collectible dolls. They were mostly young Black and brown kids wearing some combination of Chiefin Heavily, That’s An Awful Lot of Cough Syrup and earlier runs of Drakeo merch. The room wasn’t quite sold out, but turnout was significant.

The audience was here for communion as much as for the concert itself. They wanted to rap along to Drakeo hits like “Flu Flamming” and “Impatient Freestyle” as though they were sacred rites — which to many, they were. (Drakeo’s catalog received more than 100 million streams in 2024 alone.) Camera lights glowed like votive candles. The rising phenoms onstage all paid tribute to Drakeo: Lefty Gunplay even told the crowd how he dreamed of being in the Stinc Team. Desto Dubb threw out free T-shirts. Ralfy tossed clouds of money. Later in the evening, die-hard audience members competed for a Drakeo doll by answering trivia questions about his life.

The spirit of the night was bittersweet. For me and many others, it’s impossible to consider Dec. 18, 2021 as anything more than a cataclysm that could have and should have been prevented. An unremitting tragedy that permanently altered our lives — where little meaning can be derived and which even less justice has been served. But if the options are championing Drakeo’s inimitable talent and idiosyncratic character or allowing his body of work to fade into the endless algorithmic slipstream, it’s not a difficult choice. There was no battle that Drakeo wasn’t willing to fight. He never settled for less. This unswerving determination may have ultimately led to his downfall, but it also supplied the exemplary grit and integrity that produced his enduring legend.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.