Waiting for Sauvignon Blanc: Pandemic reveals Samuel Beckett as the ultimate realist

The other day while hanging around the house for a shipment of Napa Valley Sauvignon Blanc to arrive, I found myself starring in a California version of “Waiting for Godot.”

A text message assured me that the delivery would happen on Friday. Friday came and went. No wine. Saturday the same thing, but another text assured me that my order would reach me by Monday without fail.

Beyond my daily jog in the neighborhood at an ever-more torpid pace after weeks of quarantining with carbohydrates, I didn’t have any place to go. But I was especially determined not to miss this rendezvous with the delivery person. All day I waited inside, ear cocked for the buzzer.

Restless by the early evening and eager to go on my trot, I opened the front door only to find a missed delivery notice. “But I was here the whole time!” I wailed to an empty street. “How can this be?”

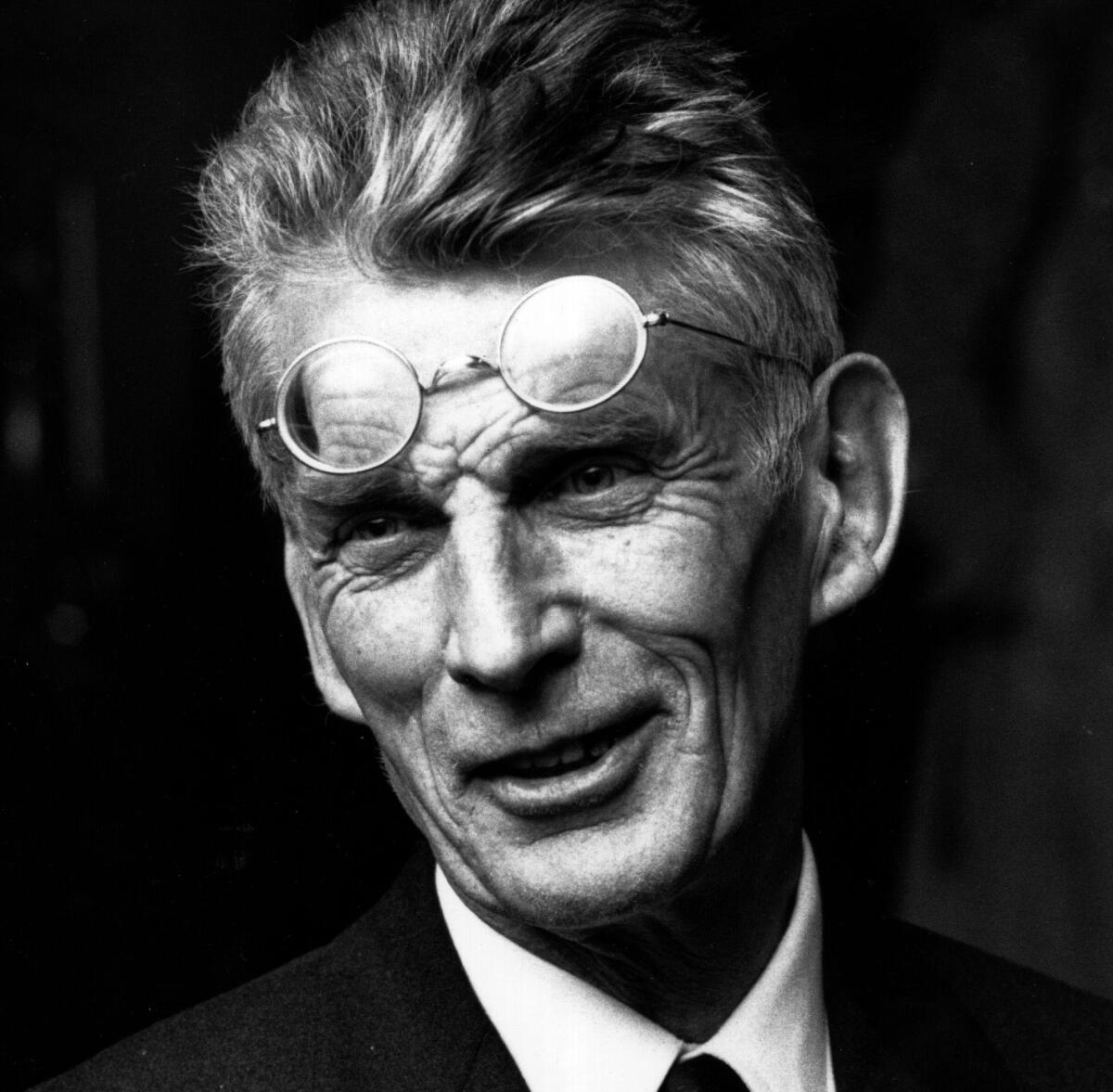

Samuel Beckett’s absurdist classic is in two acts, and my drama was far from over. I called the misnamed express delivery service and was placed on hold. A half-hour later I hung up. A glass and a half into a Cabernet, I tried again and persisted until I reached someone.

“I think there’s a problem with your delivery person,” I breathlessly complained when my purgatory of on-hold music came to a halt. “I was home all day, but the guy didn’t buzz. He just left a sticker on my door. How am I supposed to know he’s there? My mind-reading powers aren’t what they once were.”

Did I wish to file a report? Yes, if that would solve the problem of the driver’s timidity with doorbells. My customer service apparatchik explained that the call was being recorded. After I deduced that he required my consent, he went on to inform me that no complaints were being accepted at this time.

“But then why did you ask if I wanted to file one?”

Logic was of no more use to me than it was to Vladimir and Estragon, the tramps in Beckett’s play unable to ascertain the reason their meeting with Godot has yet again been postponed. Communication, likewise, was an exercise in farcical futility. Yes, the call passed the time, but as Estragon reminds Vladimir, “it would have passed in any case.”

With each passing year, my life seems to become more Beckettian. Growing older teaches the truth of the Irish playwright’s dark comedy of the decaying human body, a vaudeville of swollen feet, blurry vision and mutinous digestion. The dream of progress, mordantly parodied in the plays by characters who have settled on endurance as their best option, is of course mercilessly tested in middle age.

But the pandemic has revealed Beckett to be the true realist of 20th century theater. Stuck indoors with little to distract us from the bewilderment of our metaphysical predicament, we are like one of his immobilized characters, not scrunched into trash cans like Hamm’s elderly parents in “Endgame” but confined all the same to a narrow loop of existence.

In “The Theater and Its Double,” the mad theater visionary Antonin Artaud startlingly compared the theater to a plague. Both, in his half-cracked, half-prophetic view, provide “a kind of strange sun, a light of abnormal intensity,” in which to see not only our weaknesses and self-deceit but also our freedom and potential. “The action of theater, like that of a plague,” he writes, “... causes the mask to fall, reveals the lie, the slackness, baseness, and hypocrisy of our world.”

The theater of Beckett is a far cry from Artaud’s “theater of cruelty,” but the “strange sun” of his tragicomedies similarly lays bare what society and culture have assiduously worked to conceal. His playwriting ruthlessly strips away at everything that was mistakenly believed to be essential until what is finally exposed is being itself, raw and unadulterated.

The stage is reduced to voices and light, bodies and the meagerest of belongings. Humanity is not costumed in its elaborate fictions but depicted as a slapstick version of that “poor, bare, forked, animal” that a rain-battered King Lear called man.

Beckett’s characters are trapped in a predicament — life — that defies rational explanation. Language, which dangles the promise of communion with other consciousnesses, has a way of turning us into ventriloquist dummies. The search for meaning is a fool’s errand in a world built on a teetering foundation. Dependency is simultaneously our cross and our salvation. We can’t go on with other people; we can’t go on without them.

The writer J.M. Coetzee glimpsed the “plight of existential homelessness” in Beckett’s work as a mind-body problem: “A being that thinks” is “linked somehow to an insentient carcass that it must carry around with it and be carried around in.” The paradigmatic dramatic conflict in Beckett between a compulsively chattering inner voice and a body with its own burdensome demands is more apparent in times likes these when, removed from our busy routines, we find ourselves supine on our couches, pondering the mystery of life while plotting the next foray to the grocery store.

Beckett’s gallows humor, which finds endless mirth in the cosmic joke played on us at birth, can seem like sacrilege to true believers of the sacred myths. “Use your head, can’t you, use your head, you’re on earth, there’s no cure for that!” Hamm insolently erupts at his binned father.

Inverted piety is an inexhaustible source of laughter, but Beckett’s predominant comic mode is savagely ironic. Recalcitrant truths of the human condition are juxtaposed against the sentimental bromides that would have us believe, as Winnie chirps from the mound in which she’s inexplicably half-buried in “Happy Days,” “that not a day goes by — to speak in the old style — without some blessing.”

As movement creeps to a halt for Beckett’s characters, they come to realize in their infirmity that there never really was any possibility of escape to begin with. “What a curse, mobility!” Winnie exclaims while observing her husband crawling around in his nearby hole. The remark might seem less outlandish the longer we are away from the exhausting frenzy of our pre-coronavirus routines.

The static world of Beckett’s plays invites us to move beyond the rushed pageantry of our lives to peer into the unyielding facts of our existence. For those averse to stark truths, this might seem like depressing material for the theater. But what could be more life-giving than the perfection of form achieved by Beckett in plays that are meticulously wrought by a theatrical composer whose unfailing ear for language is matched by an unerring eye for gesture.

There’s also the relief of confronting what is always there but rarely addressed with such comic vigor. Nietzsche, in examining the origins of Greek tragedy, asked “how much did this people have to suffer to be able to become so beautiful!” Staring into the abyss, the ancient tragedians created order and meaning through art. Beckett, casting his gaze into the same void, brought forth humorous enlightenment in works that give theatrical form to the playful ways we fill in the emptiness.

Perhaps the most therapeutic hour I’ve spent since the pandemic upended our lives was listening to a BBC broadcast of Beckett’s radio play “All That Fall” one unmotivated morning. In the laughter that poured out of me as Bríd Brennan’s peevish old Mrs. Rooney hectored her neighbors on the way to meet her husband at the train station, the gulf between our social certainties and our metaphysical bafflements became hilariously apparent.

The effect was precisely the opposite of my experience with the delivery person: I felt seen. As social distancing has cast us in a Beckett tragicomedy all our own, there’s a new resonance to Vladimir’s remark to the young boy who arrives at the end of the play asking what message he should take back to the still absent Mr. Godot: “Tell him ... [He hesitates] ... tell him you saw me and that ... [He hesitates] ... that you saw me.”

Words fail Vladimir, but they don’t elude Beckett, who gives expression to that nameless condition that has suddenly come more sharply into view.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.