A ballet for us all: How ‘Appalachian Spring’ carries promise for a new beginning

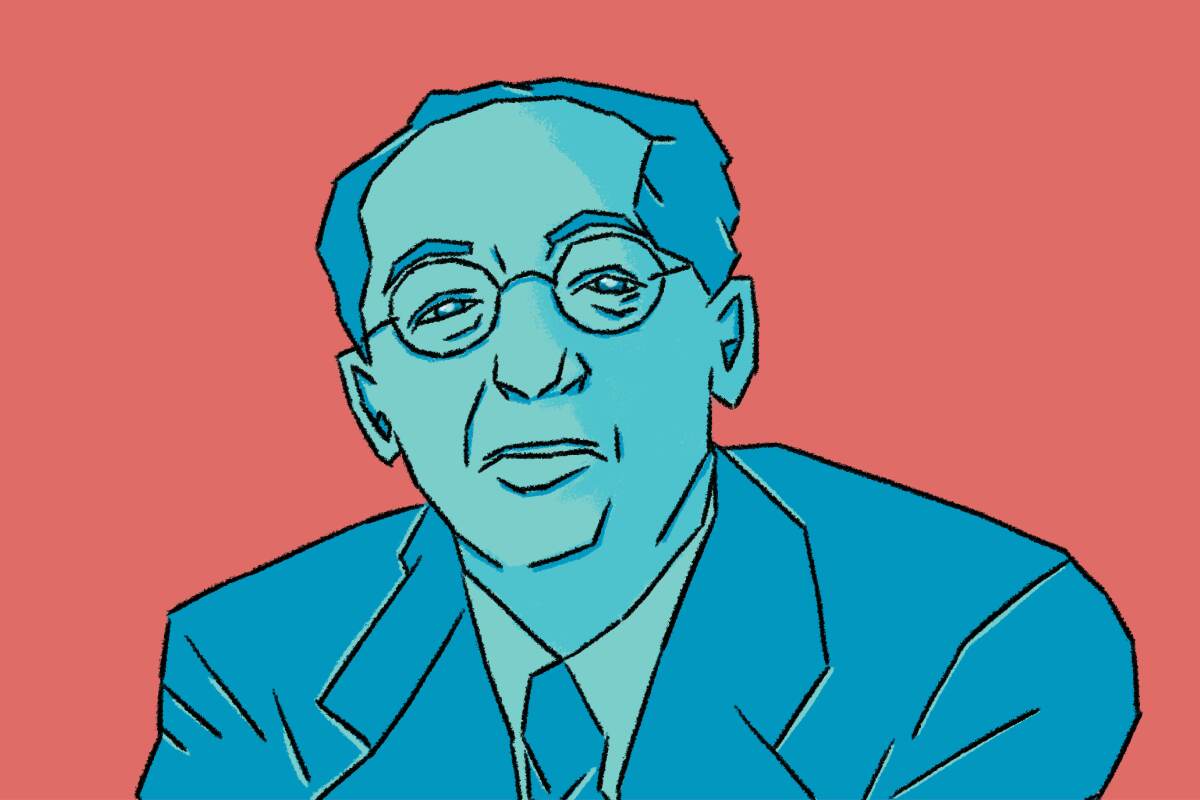

When Martha Graham’s ballet “Appalachian Spring” had its premiere on Oct. 30, 1944, in Washington, D.C., Aaron Copland was the voice of America. He had the gift to be simple. He wrote music that served the essential need for wartime American unity.

Among Copland’s wartime efforts had been “Fanfare for the Common Man” and “Lincoln Portrait,” patriotic music that miraculously avoided sentimentality and reminded us of what we were supposed to have evolved into being as a nation. Five months after D-day, “Appalachian Spring” then became the parable of a struggle that leads, with humility and grace, to a new beginning. With the premiere of an orchestral suite derived from the ballet score a year later, with the war over, “Appalachian Spring” attained a mystic glow.

It has long been a cultural mystery how Copland, this Brooklynite of Russian Jewish immigrants — someone who grew up in what he described as a drab neighborhood of other Eastern European immigrants — invented what came to be heard as the “American sound.” Yet the Holocaust and much else haunts “Appalachian Spring.” The roots of Graham’s ballet lie in the awareness of the Appalachian Trail as the slave route to freedom. Graham and Copland also had been affected by the civil conflict of the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, when the Chicago police shot and killed 10 unarmed protesters during the Little Steel Strike.

In the end, the ballet wound up being vaguely set in an antebellum Shaker village that wasn’t even in the Appalachians. A couple is to be wed and begin a new life in a new home. A pioneer woman and a revivalist preacher, with four female acolytes, represent the narrow confines of a community that honors spiritual lives of simplicity, close to nature. The music’s lasting character is its quietude that submerges hollow triumph into hallowed reflection.

Michael Tilson Thomas once described this as the mythical heritage that as Americans we all share. But is it even thinkable today, in our divisiveness, to agree on any American icon, let alone “Appalachian Spring,” which has come to be seen by some as a relic of an idyllically whitewashed America?

Copland’s music has been used as the soundtrack for Republican and Democratic campaigns wanting to signify a candidate’s sanctified Americanness, and at the same time attacked by voices on the right and the left. Copland’s patriotism was questioned when Joseph McCarthy hauled the composer in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee for his alleged communist sympathies. In an essay on Copland’s music written in 2000 on the occasion of the composer’s centenary, the musicologist Judith Tick noted that Copland in some circles already had been “rendered suspect for allegedly … imposing a homogenous identity on a diverse society.”

None of this was helped by the “Appalachian Spring”-like music used for years to sell just about anything on television commercials. Once a modernist, Copland was considered a cop-out by progressive composers. The State Department supported orchestral concert tours that included “Appalachian Spring” as American propaganda. The postwar Germans, for one, would have none of this, one critic labeling the score “pretentious, harmless, unsatisfying, feminine and unbearably boring.”

Nothing could be further from the truth. Graham’s was an incredibly brave and conciliatory ballet. Copland’s score demands our questioning of every assumption we have about American identity, whether we strive to be one people — of women and men, various gender and sexual identities, a melting pot of races and cultures and backgrounds and privileges — or whether sexual, racial, regional, political or other cultural differences make us incurably incompatible. What we hear, then, in the near inconceivable purity of sound and intent of “Appalachian Spring” is nothing less than utopian transcendence.

Ecstasy and excess, rhythm and repetition, gender and ethnicity. Lyricism, protest, healing. Critic Mark Swed’s series on the ideas embedded in every note.

The ballet opens in an exalted stillness. The music comes out of nowhere with low A’s (two short and one long) played by a handful of violas and second violins, as though two seeds planted in the earth, nothing but future promise. Seeds grow into two simple chords that rise through individual instruments with cool tranquility. A plaintive melody evolves out of this low-density harmonic exosphere. There is just enough gravity to hold the chords together, but each note is an individual with promise.

In the sections that follow, there is a duet for the intended, followed by solos for cocky groom, anxious bride in presentiment of motherhood, pioneer woman and ecstasy-exhorting revivalist. The most famous section is a set of five variations on the Shaker tune “The Gift to Be Simple,” reaching an apotheosis that is the only moment of grandiosity in the score, a bubble in need of bursting as the opening atmosphere returns, the couple taking its place among the community, a serene sense of seasons to be ever turning.

Copland’s music throughout, whether upbeat or unruffled, has the structural security of being a musical house seemingly made of a single beam, which is also the effect that Isamu Noguchi’s Noh-theater-inspired set had for Graham’s dance. Adding considerably to the cultural mix, Copland’s music was sourced from his Jewish roots, the 1920s Paris where he studied, New York modernism, jazz he regularly heard in Harlem, folk music, journeys to Mexico. The music entered into his vocabulary and took on his accent.

It so happened that Copland began and wrote much of “Appalachian Spring” in Hollywood while scoring the film “The North Star.” In the big-budget production about the Nazi invasion of a Ukrainian village, Copland confronted his own background, Copland-izing Russian Ukrainian musical traditions.

That might seem a world away from Appalachia. But it was in Paris where Copland first understood his essential Americanness, in Mexico where he was inspired to become an American populist, and in the fantasy world of Hollywood where he entered into the ultimate spirit of America. It is also worth noting that while writing the ballet score, the orchestral sound in his ear would have been that of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which had just become the first major American orchestra to appoint an American-born music director, Alfred Wallenstein.

More unexpected West Coast Americanism entered into “Appalachian Spring.” The star of the ballet’s first performances turned out to be Merce Cunningham, a member of Graham’s company allowed to choreograph his own dances. That year, Cunningham and his partner, John Cage, who had left his native L.A. five years earlier, gave their first joint concert of solo dances and music. “I date my beginning from that concert,” Cunningham wrote.

“Please capture all hearts present,” Cage, who was after Cunningham to strike out on his own, wrote the dancer just before opening night of “Appalachian Spring.“ Cunningham did. This was his last role for Graham, Copland’s music giving him permission to become himself. At the memorial in 1991 for Copland at Lincoln Center, Cage and Cunningham sat in the last row of Alice Tully Hall so they wouldn’t be seen weeping.

“Appalachian Spring” is a vision of an America not of cancellations but additions, open to all. We celebrate the 75th anniversary of the end of the last world war this week while fighting a new world war against a novel coronavirus, all the while deciding on America’s future with what is forecast to be an unprecedentedly divisive presidential campaign. A parable of a struggle that leads, with humility and a grace, to a new spring takes on new necessity.

Starting points

Given the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s all-American, all-”Appalachian Spring” sound, its two recordings are worth hearing.

Zubin Mehta’s 1976 recording has been newly remastered and is bold and spectacular.

Leonard Bernstein’s 1960s recording with the New York Philharmonic was preferred by many (including Copland) because of its vitality, but his rapt, effusive, overflowing 1983 recording with the L.A. Phil holds all of Copland’s world in its hands.

Aaron Copland was a fine conductor who recorded the score several times. His version with the Boston Symphony is the classic.

Martha Graham’s televised production of the ballet has been restored in 4K and released on Criterion DVD with lots of worthy extras. But a film of the original cast that Graham’s company has posted on YouTube, as poor as the video quality may be, is the riveting ideal.

With live concerts largely on hold, critic Mark Swed is suggesting a different piece of recorded music by a different composer every Wednesday. You can find the series archive at latimes.com/howtolisten and support Mark’s work with a digital subscription.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.