TV coverage of Bush v. Gore is a scary reminder of what can go wrong on election night

It was well past 3 a.m. Eastern time on Nov. 8, 2000, when NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw looked into a camera on his network’s election night set and delivered what is likely the most humbling remark to come from a television journalist.

“We don’t have egg on our face,” Brokaw said. “We have omelet all over our suits.”

The words came after the embarrassing debacle of the networks having to retract the call for the winner in the presidential election between Vice President Al Gore and Texas Gov. George W. Bush.

Bush was declared the victor that night after he was awarded Florida and its 25 electoral votes, giving him a slight edge over Gore, who would win the popular vote. But the networks soon had to pull back their call, as the vote margin between the candidates in the state narrowed as more ballots were counted.

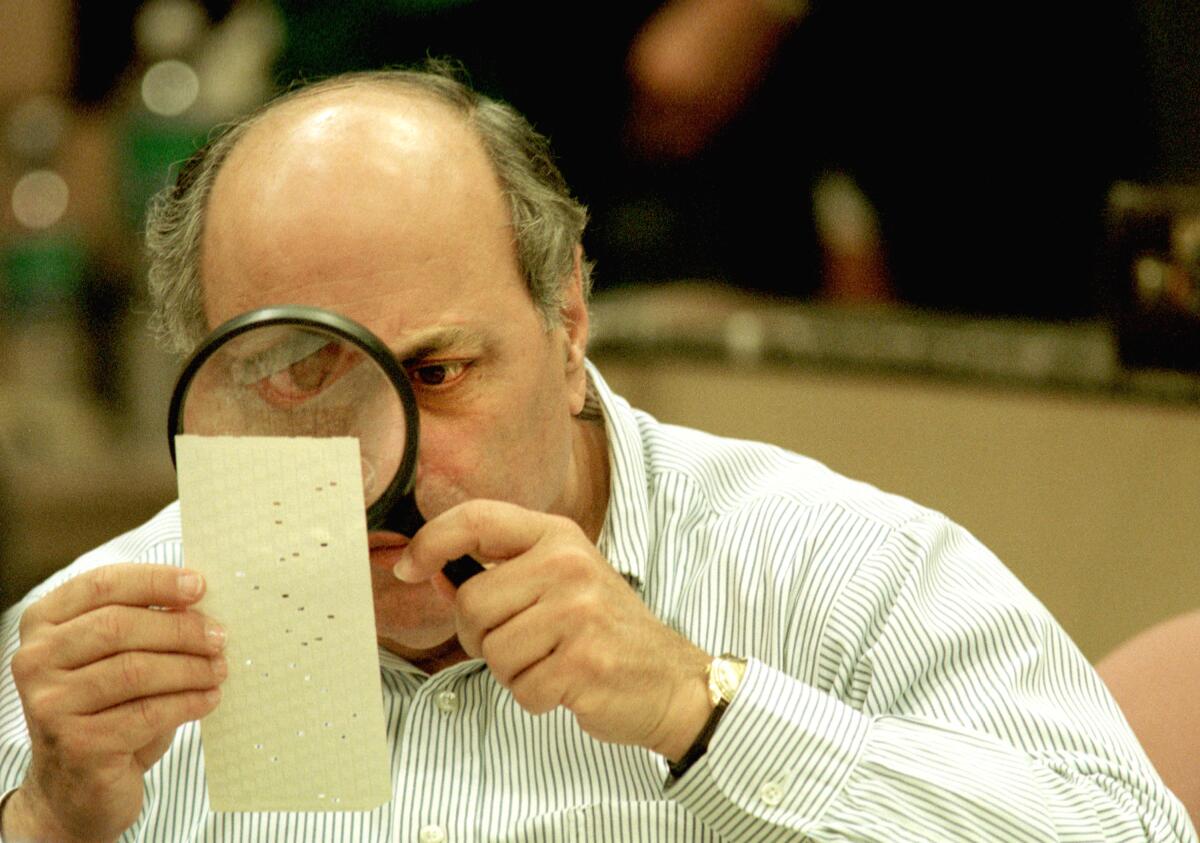

What ensued in the next 35 days was unprecedented in American history as TV news dispensed around-the-clock reports on recounts, voting irregularities, protests and legal challenges. They preceded a U.S. Supreme Court decision that ultimately voted 5-4 in favor of stopping a statewide Florida recount and delivered the election to Bush.

The images from those chaotic days of Florida election officials examining punch-card ballots — looking for “hanging chads” or “dimpled chads” — are likely to be evoked when the votes are counted in November, as the nation conducts a presidential election amid the public health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Political theater without the roar of the crowd? The stakes are high as Democratic and Republican conventions come to a screen near you.

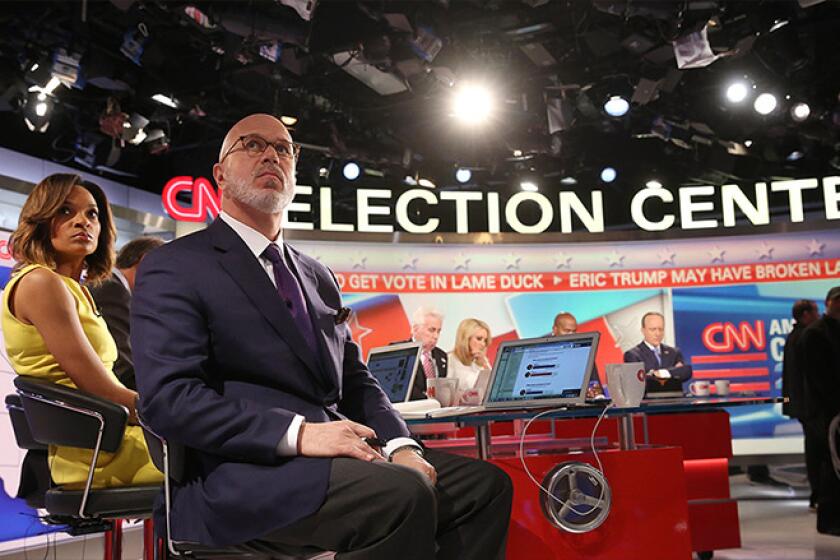

By the time election night arrives, TV viewers already will have seen how social distancing to deter the spread of the coronavirus permeates every element of the 2020 presidential campaign, starting Monday with the Democratic National Convention, followed by the Republicans’ event. Both conventions will be a shell of previous gatherings with speakers appearing virtually, while TV anchors will be at their home bases in Washington or New York.

Conventions, election night and the campaign trail will look a lot different on TV to political junkies as the 2020 race heats up.

Neither presumptive Democratic nominee former Vice President Joe Biden nor President Trump, who accepts the Republican nomination on Aug. 27, are expected to deliver their speeches in front of cheering crowds of supporters.

While it will be a challenge to turn the conventions into compelling television — broadcast networks ABC, CBS and NBC and cable news channels CNN, Fox News and MSNBC will carry live coverage in prime time — it pales before the monumental task of getting the vote count right on Nov. 3. The expected unprecedented amount of mail-in voting — a process Trump has already called rigged and corrupt without offering proof — guarantees a tabulation process that will be painstakingly slow and could go on for days or weeks. If the election is close, legal challenges are likely to abound.

Network TV news executives know what is at stake because nearly 20 years ago they got it very wrong.

Exit polls taken of voters on Nov. 7, 2000, indicated a victory for Gore. When ballots were tabulated that night by the Voter News Service — the consortium formed by the networks and the Associated Press to collect the results — Gore was awarded Florida shortly after polls in the state closed, only to have it pulled back from his column later in the night.

Tim Russert, moderator for NBC’s “Meet the Press,” had been using a black marker and erasable whiteboard in the days leading up to the election to depict the various combination of states that would bring one of the candidates to the 270 electoral votes needed to win. With Florida back in play, Gore and Bush were tied at 242, which prompted Russert to write three words that became a mantra political pundits still cite today: “Florida, Florida, Florida.”

After midnight in the east, a surge of votes came in from Volusia County in Florida. It gave Bush a large enough lead that Fox News called the state and the election for the Republican nominee. The other networks, whose analysts were working off the same data, followed several minutes later. Only the AP held back to do its own vote count.

After seeing the results announced on television, Gore called Bush to concede the election. But by 3:17 a.m. Eastern, the Florida secretary of state’s website showed Bush’s lead shrinking to 565 votes. Gore called again to rescind his concession, a stunning moment in presidential politics.

The networks had to retract the announcement of a victory for Bush and declare the race too close to call. But for the Gore campaign, the damage had been done.

“It wasn’t ambiguous,” said Michael Feldman, managing director of the Glover Park Group, who served as an advisor to Gore’s 2000 campaign. “All the networks said George W. Bush will be the 43rd president of the United States, with flags waving and graphics — that was what the country saw. No matter what the actual vote was in Florida or anywhere else, Gore was always going to be the spoiler trying to unwind something that had happened even though, as we found out later, it hadn’t happened.”

Conventions, election night and the campaign trail will look a lot different on TV to political junkies as the 2020 race heats up.

The initial erroneous election call led to conspiracy theories. The Fox News analyst who called the race first, John Ellis, was a first cousin of Bush. While Ellis was a respected political expert previously employed by NBC News, his presence at a network decision desk, where statisticians and political scientists crunch poll numbers, votes and historical data to project winners, appeared to be a conflict of interest.

“What was someone related to Bush doing in any position of responsibility to call an election?” said Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics.

There was also a rumor that Jack Welch, chairman of then NBC parent General Electric and a longtime Republican backer, was urging his network’s news division to call the race for Bush.

But the main source of the problem was erroneous voting results that came in from Florida’s Volusia County. When the bad data was figured into the state’s total late that night, the network news operations, confident after having a 52-year record of calling presidential races accurately, did not question it.

Bragging rights also were at play. Network news divisions took pride in projecting a winner first.

“There was a lot of competitive pressure to not get beat and not be five minutes behind somebody else,” said Al Ortiz, who worked on CBS News’ election coverage in 2000 and is now vice president of standards and practices for the division. “In the years that followed — and today — there is a lot more patience. If you’ve got a county that goes completely differently from its history or in the models we have, it sets off a round of questioning now that it didn’t automatically back in 2000.”

Even Gore presumed the networks were right, which led to his initial concession call. “Had he known at the time what was actually going on, he probably wouldn’t have made that call,” Feldman said. To this day, Feldman believes the call hampered Gore and helped Bush in the court of public opinion during the weeks that followed.

“Anybody who’s run a recount in any race from president to dog catcher will tell you if you have a lead at the outset and you’ve been declared the winner,” Feldman said, “that is a huge advantage in the process.”

The networks — whose news presidents were called before Congress, where they delivered mea culpas over the breakdown of the 2000 election calls — have taken a more cautious approach ever since.

In 2004, the closest presidential race since 2000, the networks did not declare a winner until the day after election night, when campaign officials for Democratic nominee John Kerry determined there were not enough uncounted provisional votes in Ohio to overtake incumbent Bush’s narrow lead in the state. (Exit polls had pointed to a Kerry victory, further evidence they had become less reliable.)

When Ohio was close again in the 2012 presidential election, Megyn Kelly, then a Fox News anchor, marched down to the network’s decision desk to have analysts explain why the state — and the election — were being called for Barack Obama over challenger Mitt Romney. (The network’s Republican analyst, Karl Rove, had disputed the results.) The moment showed how audiences had become used to seeing their partisan viewpoints reflected in the cable news channels they watched and needed some convincing when the proceedings were not going their way.

Early exit polls in 2016 led networks to believe Hillary Clinton was on her way to beating Trump. The misfire led Fox News and the AP to team up with the University of Chicago to develop a new voter survey that increases the number of people questioned and puts a greater emphasis on early voting. Since then, Fox News has been calling races earlier than its competitors during special elections, the 2018 midterms and the 2020 primaries, with no mistakes so far.

ABC, CBS, NBC and CNN use the firm Edison Research to collect voting data for their election night calls.

While the networks are more careful about reporting the results, an election night that extends into days or weeks involving Trump, who has already assailed the process, means viewers could still be in for a rocky ride.

“I am concerned about that because we are much more polarized than we were in 2000,” Sabato said. “It doesn’t take much to inflame people anymore, and the TV coverage is going to be reflecting social media, which is going to be reflecting the TV coverage, so they’re going to be feeding into one another in this horrible polarized loop.”

Audiences for hockey and golf are surging, and baseball is bringing in younger viewers, as people look for a break from streaming.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.