Review: Extreme alienation reigns in the Hammer Museum’s (unopened) biennial

- Share via

As I drove over to the UCLA Hammer Museum in Westwood to see the latest iteration of its biennial exhibition, the radio news broadcast a litany of awfulness.

Coronavirus infections across the country had broken a record, with nearly 120,000 new cases in one day. The president of the United States was threatening to disenfranchise tens, even hundreds of thousands of voters in a corrupt attempt to secure his reelection. The Supreme Court had heard arguments that a secular nation should allow government discrimination against LGBTQ citizens under claims of religious faith.

The next day, I went to San Marino to see the other half of the biennial exhibition, which is being shared with the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens. As at the Hammer, the show has been installed for a while, awaiting the lifting of museum closure orders from the county. (It was supposed to be on view over the summer.) That’s not looking immediately promising, as health officials report that the disease is widespread and increasing in L.A. with bad daily numbers not seen since August.

The radio on my second trip wasn’t much more encouraging. Such is the nature of news.

Radio often depends on newspapers for content, so Charles Baudelaire, the 19th century French journalist who also pretty much invented modern art criticism, popped into my head. “Any newspaper, from the first line to the last, is nothing but a web of horrors,” he wrote. “I cannot understand how an innocent hand can touch a newspaper without convulsing in disgust.”

Fitting right in at the Huntington, artist Sabrina Tarasoff built a Halloween-style haunted house — complete with gory tableaux, creepy video projections, dank caverns and black-lighted mannequins. All these elements, witty and sobering, are drawn from archives of Beat, punk and Postmodern art events held over the last 50 years at Beyond Baroque, the venerable literary and arts center in Venice. Profound social trauma is an artistic staple.

I don’t know what the dandyish Baudelaire, who titled his book of lyric poetry “The Flowers of Evil” (it was suppressed by French authorities), might have thought of the art in “Made in L.A. 2020: a version.” But I do think he would have been keen on that subtitle — “a version” does double duty, including the modestly small “a.”

On one hand, it underscores something too often taken for granted but worth remembering. Museum biennials are never comprehensive; they’re only a version.

On the other hand, the language frames a particular ethos. Abhorrence lurks in “a version,” as Tarasoff’s haunted house suggests. Insinuations of extreme alienation are everywhere.

The show’s guest curators are Paris-based Myriam Ben Salah and L.A.-based Lauren Mackler, both of whom work independently, along with Hammer assistant curator Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi. They chose 30 artists, down just two from 2018.

Buck Ellison’s photographs, fabrications staged with actors, assess the underside of white identity. Most haunting is a deft family portrait that shows a 6-year-old Erik Prince, who went on to found the private military contractor Academi (formerly Blackwater), and his teenage sister Betsy DeVos, later U.S. Secretary of Education, as something recalling creatures who might have escaped from “The Omen.” Mathias Poledna’s queasy short film “Indifference” turns the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire into an elegant dream, fusing lush nostalgia with the blunt trauma of modernity.

Patrick Jackson’s proposal for a monument pits private respite against a public promise of relief. A cozy domestic breakfast nook is tucked away, hidden behind a sleek, shiny, charmless black wall fronted by a hunched boulder pierced by a drinking fountain. A paltry public amenity is endowed with grandiose glamour.

The catalog to the exhibition reports that the curators did more than 300 studio visits — a big, exhausting number, but still modest compared with the local quantity of artists. From that the curators knitted together a general point of view.

One salient quality: Most of the 30 artists are L.A. immigrants, hailing from elsewhere in the U.S. or abroad. Several choose to live and work in more than one place. The pointed selection judiciously rejects blood-and-soil nationalism, even on a civic level, that stains today’s larger social and political culture. It doesn’t matter where you’re from, it only matters what you do.

An element of performance — Onyewuenyi’s curatorial specialty — ran headlong into the pandemic’s essential demands for social distancing. Regular performances planned by Ligia Lewis for a small, bright yellow dance pad tucked into a Hammer gallery corner (otherwise a dead space in any room) had to be temporarily jettisoned.

In a nice installation touch, Brandon D. Landers’ buoyant palette-knife paintings of families and friends encircle Aria Dean’s partly mirrored glass room, where surveillance cameras tracked an actor inside and wearing a bodycam. The paintings provide a mute, inquisitive audience for the mirrored room’s meditation on mediation, which now stands as an empty stage set that is roped off and cannot be entered. The alienation effect is further estranged by an exhibition currently closed.

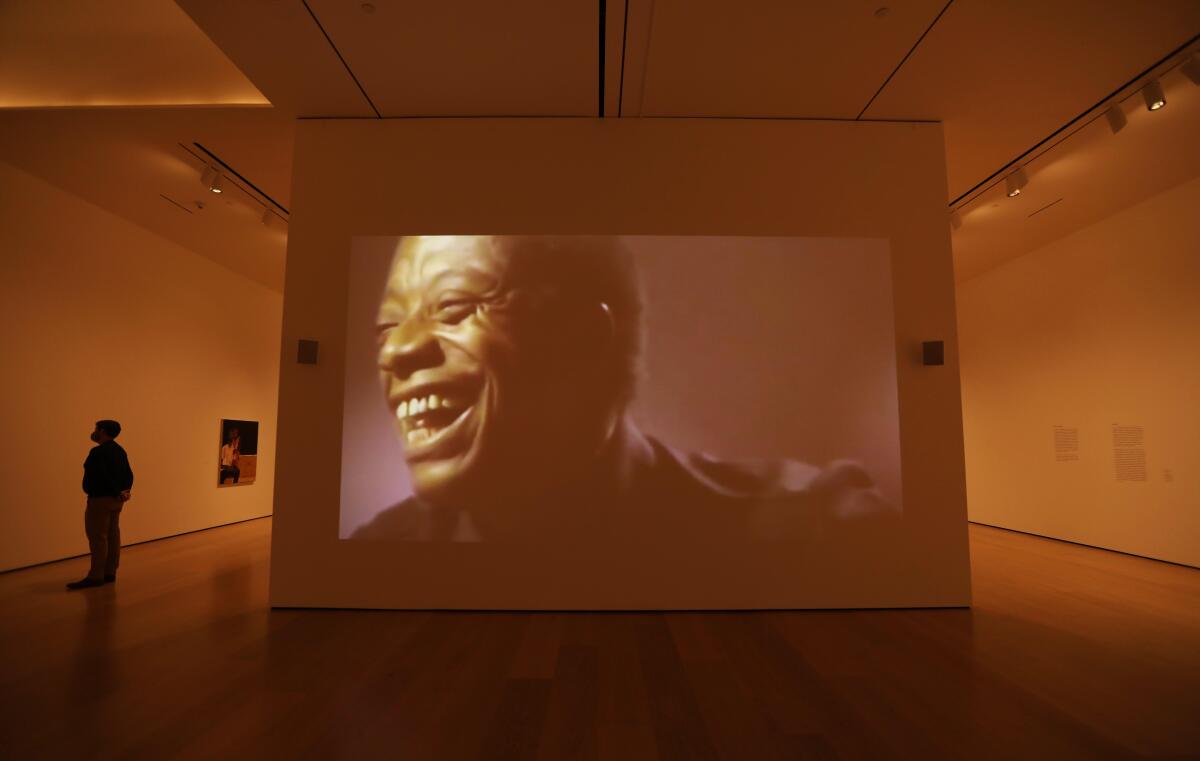

Photographs, videos and projection screens are encountered again and again in the show — almost too often, if understandably so. Some, like Harmony Holiday’s poignant film-montage remembrance of the great James Baldwin, will tear at your heart. But, in Pandemic World, life lived online, on social media and on Zoom ramps up yearning for tactile visual experience, which the elusive surfaces of photographs, films and videos can’t fulfill.

To compensate, there’s Nicola L’s “Pénétrables.” A series of participatory canvases and a room-size installation feature trousers, sleeves and face masks built into the art’s surfaces. The audience is meant to stick arms, legs and head inside.

The show fudges a bit, since the late artist’s “Pénétrables” were begun in the 1960s, long before her 2016 move to Los Angeles. (She died 18 months later at 86.) Before the pandemic, a visitor could physically penetrate this art’s skin — but no longer, disinfectant wipes or not.

Quarantine interrupted the show in other ways. Ser Serpas typically gathers up discarded junk — broken toys, household litter and cast-off furniture — from a show’s neighborhood, which she then lays out in a grid for examination. Rational order rubs against irrational desire, accidental consumption and inevitable loss, while the detritus gets returned to the trash when the show ends.

Serpas, however, describes her Hammer and Huntington installations as “potential” works of art. Stuck in Switzerland as “Made in L.A.” approached, she had to let others do the scavenging and composing for her.

The two halves of the show feel very different, too, even though all 30 artists have work in both venues. Devoid of people, the Hammer’s conventional, white-cube galleries seem rather airless and aloof. The Huntington feels more fully engaged, perhaps because the lavish gardens (though not the museum or library) are open, and masked visitors are out and about.

Also, some artists are shown in dialogue with other Huntington specialties, which adds a conversational liveliness.

Monica Majoli’s ethereal, erotic watercolors based on the defunct men’s lifestyle magazine Blueboy — think gay Playboy, especially popular in the 1970s and ’80s, just before the AIDS pandemic — resonates with the stunning 18th century Thomas Gainsborough painting of that name that is the international superstar in the museum’s collection. A displayed archive like Mario Ayala’s underground Chicano magazines — source material for skilled airbrush paintings that evoke vernacular altarpieces — is thrown into high relief in the vicinity of a heavily Anglo-American library in a town with Indigenous roots in Mexico.

Ellison tucked one of his acutely detailed photographs of the attributes of white ruling-class society into the American galleries, next to a double-portrait by Bostonian John Singleton Copley showing 18th century British landed gentry. A life-sized photocollage by Kandis Williams has Henry E. Huntington, billionaire robber baron and founder of the place, merging with Goya’s rendition of the pre-Olympian Greek god Saturn, wild-eyed as he devours the bloody corpse of his own murdered son.

Museums, after all, are theatrical spaces for historical narratives and their ongoing revisions. Some artists make that clear.

Jill Mulleady greatly enlarged a pastiche of Cézanne’s landscape painting, “Interior of a Forest” (circa 1885), then set its dense woods on fire. Her big canvas is split in two, framing a doorway to the gallery for the museum’s slightly earlier sculpture of a renegade Palmyran queen in chains.

The white marble sculpture was carved in American artist Harriet Goodhue Hosmer’s Roman studio just as her home country lurched into the Civil War. Nearby, two barefoot Jackson sculptures of prodigiously bearded good ol’ boys are laid out horizontally on the gallery floor, seemingly embalmed in time and space. The juxtapositions of Mulleady, Hosmer and Jackson suggest a slyly feminist storyline engineered in concert with the curators.

Will “Made in L.A. 2020: a version” ever open to the public? Museum spokespersons are optimistic. For safety’s sake, if county health officials do give the green light, the museums envision just 25 visitor reservations per hour. The galleries at both venues will remain installed until March.

Meanwhile there’s the catalog, which begins with a handsome if portentous photograph by William Hertrich, Henry Huntington’s head gardener. Shot in the famous cactus garden, the black-and-white picture of a colossal Agave atrovirens shows an immense, asparagus-like stalk shooting skyward from the center of the big plant’s imposing rosette of serrated leaves.

The agave, a type of century plant, lives a long life — then blooms once and dies.

Taken in 1929, the photograph of abundant life and imminent, flame-out death was captured just as greed-soaked America was about to crash and burn in the poverty and chaos of the Great Depression. The shuttered 2020 L.A. biennial is timely, even if it never opens.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.