Column: Yes, the Capitol is a ‘symbol of democracy.’ One with a really troubled history

- Share via

“Symbol of democracy.”

The phrase echoed in one form or another throughout social media on Wednesday as swarms of Trump supporters smashed their way into the U.S. Capitol building, instigated by a bitter president who refuses to recognize his electoral defeat. Images of extremists sporting MAGA hats and Trump banners, parading around the building — at least one carrying a Confederate battle flag — was a direct assault on democracy’s most potent symbol and, ultimately, democracy itself.

“The Capitol building is the center and sacred symbol of democracy,” tweeted Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart, a Republican from Florida. “Today’s violent actions undermine the principles and values that our nation was founded on.”

Alexander De Croo, prime minister of Belgium, expressed “shock and disbelief at ongoing events at the US Capitol, symbol of American democracy.”

It was a sentiment echoed throughout social media by political leaders, reporters and casual observers alike. The U.S. Capitol, with its graceful Neoclassical architecture, evocative of representative government systems that date back to Classical antiquity, was being invaded by the hordes. What was supposed to be the site of democratic deliberation now featured a screaming shirtless guy in a Mad Max Viking ensemble and a rioter trying to run off with a lectern.

The U.S. Capitol was being debased.

The Capitol is an important symbol of democracy. But it’s a complicated one — “the people’s house” built by slave labor and designed, in countless ways, to erase their presence afterward.

The so-called “Temple of Liberty” is made from Aquia Creek sandstone that was quarried, in part, by slave labor. Enslaved laborers were heavily involved in its construction. The Statue of Freedom that sits atop the Capitol’s dome, designed by sculptor Thomas Crawford and completed in 1863, was shaped by the institution of slavery. An enslaved foundry worker, Philip Reid, helped cast the figure, yet Freedom dons a Roman helmet rather than a “liberty cap” — a soft cap that served as a symbol of emancipation in the 1850s — because Jefferson Davis, who was serving as U.S. Secretary of War at the time the sculpture was being fabricated, objected that it didn’t represent “people who were born free and would not be enslaved.”

So, yes, the aesthetics of the U.S. Capitol were shaped by a guy who would later lead the Confederacy.

Moreover, statues inside the building pay tribute to figures such as former President Andrew Jackson, architect of Indian removal policy; former Vice President John C. Calhoun, who considered slavery “a positive good”; and Junipero Serra, the Spanish friar whose statues have been coming down for the way his mission system wreaked havoc on Indigenous communities in California.

In the Capitol building, idealized narratives of liberty and democracy rest on brute force.

Beyond the issues of labor, there are the ideologies embedded into the very architecture.

Historian Lyra D. Monteiro, in a thorough essay published last fall, catalogs some of the links between white supremacist ideals and the ways in which Neoclassical art and design have been deployed in the U.S. “Ancient Greece and Rome offered the perfect heritage for white Americans,” she writes, “they affirmed the ancient nobility and capacity for rule of the white race, while also offering a model of righteous empire and civilized slaveownership.”

These ideas are also examined in “Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History From the Enlightenment to the Present,” a collection of essays published by University of Pittsburgh Press last year.

Scholar Mabel O. Wilson notes that Enlightenment thinkers — among them Thomas Jefferson, who chose the Capitol’s architect — valued “the power of reason and the virtues of equality, justice, and freedom.” Yet these very same thinkers used reason as a way of justifying racial hierarchies, rationalizing that white Western civilizations were more evolved; African and Indigenous ones, less so. “Black bodies and blackness for Jefferson and for others of his era proved an impenetrable threshold to reason,” writes Wilson.

Americans are used to saying, ‘It can’t happen here.’ On Wednesday, it did — and the democracy we crow about exporting abroad was shaken to its foundations.

“Race and Modern Architecture,” which was edited by Wilson, along with scholars Irene Cheng and Charles L. Davis II, also features an essay on the Capitol building by historian Peter Minosh. In it, he chronicles the racial attitudes of the structure’s designer, William Thornton, who worked to send freed slaves back to Africa — a way of establishing a semi-colonial outpost on the continent, but also a way of eliminating the presence of freed Black men and women in the U.S. Interestingly, his design of the Capitol building (which has been added to over the decades by others) largely avoids reference to the Southern plantation economies that helped fund it.

“The absolute transparency between citizen and state fashioned in the Capitol claims to provide universal access to government,” writes Minosh, “but it ultimately renders unseen and unheard the multitude of the unrepresented enslaved — robbing them of their voice.”

Last month, President Trump signed an executive order that sets Classical architecture as the preferred style for new federal buildings across the U.S. and as the “default architecture” (with some exceptions) for federal buildings in Washington, D.C.

As the order notes, George Washington and Jefferson “sought to use classical architecture to visually connect our contemporary Republic with the antecedents of democracy in classical antiquity.” Blast from the past.

There have been gestures in the Capitol to acknowledge other histories in recent years. In 2012, a commemorative marker was installed to pay tribute to the enslaved workers who constructed the building. Over the years, depictions of Sojourner Truth, Rosa Parks and Chief Standing Bear — who was at the center of an 1879 court case that established Native Americans as “persons” — have joined the ranks of other historical statuary in the building.

To see an extremist proudly toting a Confederate battle flag around the building on Wednesday was shocking. Though less shocking once you realize that in one photo, the flag-bearer walks before a portrait of Calhoun. In some ways, it was the building’s history and U.S. history come to light.

The image was a stark representation of a faction in our country who want our civic symbols and the narratives behind them to remain unchanged. As Monteiro also notes in her essay, Neoclassical architecture was a popular plantation style, a way of conveying power and authority in areas where whites were in the minority. And it reflected the ongoing whitelash that Trump has led — with gusto — in the years since he took over the presidency from the Obamas, whose stories don’t fit so tidily into gung-ho American narratives about freedom and liberty.

The Capitol is indeed a symbol of democracy — a troubled one, but an evolving one. One whose narratives are not yet fully written. That will be up to us.

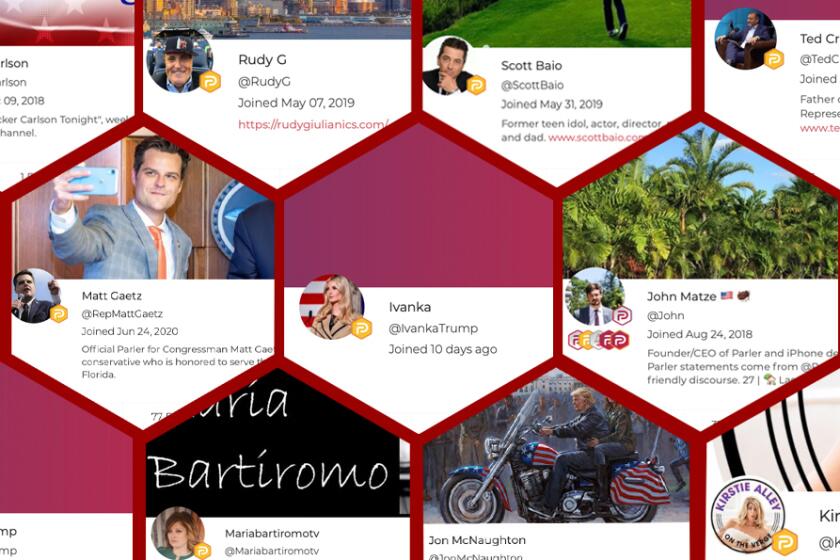

Social media platform Parler looks like it was designed by a pharmaceutical firm and sounds like a symphony composed of one note: conspiracy theory.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.